The year is 2025. We live in a world saturated with messages, a constant hum of persuasion aimed at capturing our attention and influencing our choices. From the flickering screens in our pockets to the expansive digital billboards that adorn our cities, advertising is an inescapable part of modern life. But this pervasive presence has a long and complex history, one that grapples with the very nature of influence and the ethical boundaries of communication. The concerns we have today about artificial intelligence manipulating our desires are not entirely new; they are echoes of debates that have raged for decades, if not centuries.

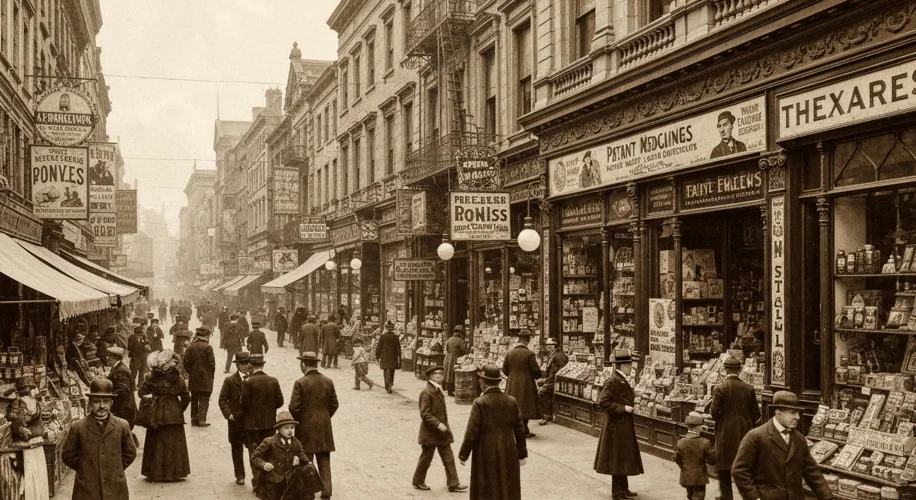

Long before the advent of sophisticated algorithms, the early days of mass advertising, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were marked by a wild west mentality. Products were often misrepresented, and claims bordered on the fantastical. Think of the “miracle cures” peddled in patent medicines, promising to alleviate everything from baldness to lethargy with a single bottle of dubious concoction. These early advertisers, operating with little regulation, employed a potent mix of psychological appeals, often playing on people’s hopes, fears, and insecurities. The rise of newspapers and magazines as mass media outlets amplified their reach, making these persuasive techniques accessible to millions.

One of the key figures in the nascent field of advertising, Edward Bernays, nephew of Sigmund Freud, famously championed the idea of “engineering consent.” In his 1928 book, “Propaganda,” Bernays argued that manipulation of public opinion was a necessary tool for a functioning democracy, allowing leaders to guide the masses towards beneficial decisions. While he presented this as a force for good, his theories also laid the groundwork for understanding how persuasive techniques could be used to shape consumer behavior on an unprecedented scale. Bernays’ work highlighted a tension that remains relevant today: the line between informing consumers and subtly coercing them.

As advertising evolved, so too did the critiques. By the mid-20th century, with the proliferation of television and radio, concerns about “hidden persuaders” and subliminal advertising began to surface. Vance Packard’s influential 1957 book, “The Hidden Persuaders,” exposed the use of psychological research and Freudian concepts to tap into consumers’ unconscious desires and fears. Packard argued that advertisers were exploiting the vulnerabilities of the populace, encouraging mindless consumption and creating artificial needs. This period saw the beginnings of advertising reforms, with regulatory bodies like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the United States slowly gaining power to curb deceptive practices.

However, the true seismic shift in advertising’s ethical landscape arrived with the digital age and, more recently, the explosion of artificial intelligence. Today’s AI-powered advertising is a far cry from the simple print ads of yesteryear. Algorithms can now analyze vast amounts of data about our online behavior, preferences, and even emotional states, allowing for hyper-personalized and incredibly persuasive messaging. AI can craft ad copy, select optimal timing and placement, and dynamically adjust campaigns based on real-time user responses. This level of sophisticated targeting raises profound ethical questions.

Are these AI-driven campaigns merely efficient marketing, or do they cross a line into manipulation? When an AI can predict and exploit a moment of vulnerability – perhaps during a period of personal distress or financial strain – to push a product, where does ethical advertising end and exploitation begin? The ability of AI to learn and adapt means that its persuasive capabilities are constantly improving, potentially outpacing our ability to recognize and resist them. This raises concerns about “shameful” advertising, not necessarily in its content, but in its insidious effectiveness, preying on psychological triggers that we may not even be aware of.

The consequences of unchecked persuasive advertising, amplified by AI, could be far-reaching. It could exacerbate societal inequalities, as those with less access to critical media literacy or with pre-existing vulnerabilities become more susceptible to manipulation. It could foster a culture of relentless consumerism, driven by manufactured desires rather than genuine needs. Moreover, the opaque nature of AI algorithms means that accountability for unethical practices can become blurred, making it difficult to identify who is responsible when persuasive tactics become harmful.

As we look back at the history of advertising, we see a continuous evolution of both its power and its ethical challenges. From the snake oil salesmen of the past to the sophisticated AI targeting of today, the core tension remains: how do we harness the power of communication to inform and connect without exploiting human psychology? The ongoing discussions about AI in advertising are not just about technology; they are about preserving human agency and ensuring that persuasion serves, rather than subverts, our well-being. The “first descendant” of this ethical debate is the realization that the tools may change, but the fundamental responsibility to communicate honestly and ethically remains constant.