The crackle of static, the hum of vacuum tubes, and the intense focus of a handful of strategists huddled around a glowing screen – this was the nascent world of strategic computing. Long before the term “video game” conjured images of bustling arcades or intricate online worlds, the seeds of strategic simulation were being sown in the sterile, high-stakes environments of military planning and Cold War anxieties. The evolution of strategic computing is a fascinating journey, tracing a path from abstract war games designed to explore hypothetical conflicts to the sophisticated real-time strategy (RTS) titles that now captivate millions, demanding intellect, rapid decision-making, and masterful resource management.

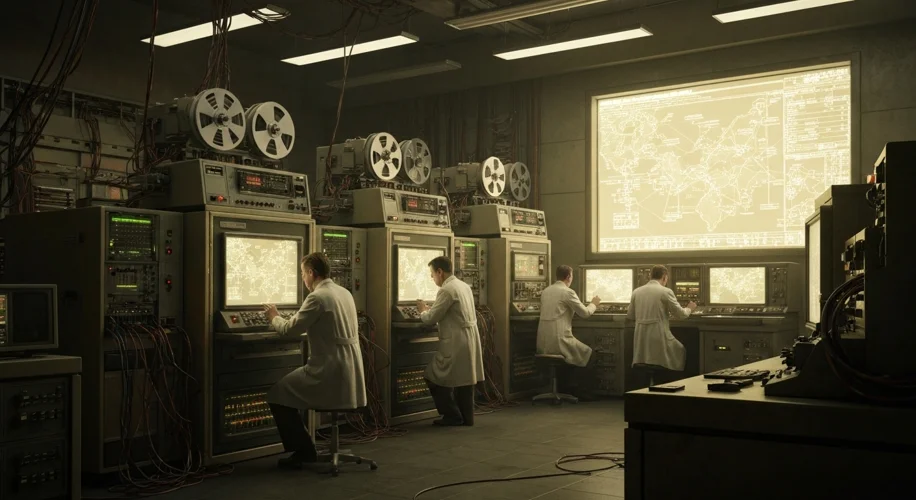

In the shadow of the atomic bomb, nations grappled with the terrifying prospect of total annihilation. This existential dread fueled a desperate need to understand the mechanics of war, not just on the battlefield, but in the complex interplay of politics, logistics, and human psychology. Early computer simulations, often the brainchild of visionary mathematicians and military strategists, emerged as powerful tools for this exploration. These weren’t games in the entertainment sense; they were sophisticated models, fed with vast amounts of data, designed to test the efficacy of different strategies and predict the outcomes of hypothetical conflicts.

The roots of this can be traced back to the mid-20th century. Pioneers like John von Neumann, a towering figure in mathematics and computing, explored game theory and its applications to strategic decision-making. His work laid the theoretical groundwork for understanding conflict as a mathematical problem, where rational actors make choices to maximize their gains. These early explorations, while abstract, were the intellectual ancestors of the complex simulations we see today.

One of the earliest and most influential examples of this early wave was the “RAND Corporation’s Air War ” model, developed in the 1950s. This wasn’t a game played with joysticks and pixelated units, but rather a complex system where human “players” made decisions for different sides, inputting their choices into early computers that then calculated the consequences. The goal was to explore the dynamics of strategic bombing and air defense, allowing strategists to run through numerous scenarios that would be impossible to replicate in reality. These simulations were often painstaking, requiring hours of data entry and analysis, but they offered an unprecedented glimpse into the potential outcomes of nuclear warfare.

As computing power grew and technology advanced, these simulations began to evolve. The 1970s and 1980s saw the emergence of wargames that moved beyond purely military applications, entering the realm of business strategy and even early forms of entertainment. These games, often played on mainframe computers or early personal computers, started to incorporate more sophisticated economic and political models, demanding that players manage resources, develop infrastructure, and engage in diplomacy alongside military might.

The true explosion in strategic computing, however, arrived with the advent of personal computers and the rise of the Real-Time Strategy (RTS) genre. Games like “Dune II” (1992) are widely credited with defining the core mechanics of the RTS genre as we know it today. Players were tasked with gathering resources, building bases, training armies, and engaging in combat, all in real-time. The speed at which decisions had to be made, combined with the need for careful planning and tactical execution, created an entirely new kind of intellectual challenge. The resource management aspect – harvesting spice, constructing refineries, and expanding one’s territory – was as crucial as the battlefield prowess.

Following “Dune II,” the RTS genre rapidly matured. “Warcraft: Orcs & Humans” (1994) and its successor, “Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness” (1995), brought a rich fantasy setting and an even greater emphasis on base-building and unit diversity. But it was perhaps “Command & Conquer: Tiberian Dawn” (1995) and then the iconic “StarCraft” (1998) that truly cemented the RTS genre’s legacy. “StarCraft,” in particular, became a cultural phenomenon, lauded for its meticulously balanced factions (Terran, Zerg, and Protoss), deep strategic complexity, and the sheer skill required to master its gameplay. It fostered a thriving competitive scene, with professional players and tournaments drawing massive audiences, demonstrating the profound engagement these games could inspire.

The impact of strategic computing extends far beyond the digital battlefield. The skills honed in these games – critical thinking, resource management, long-term planning, and rapid adaptation – are directly transferable to real-world challenges. Businesses use simulations to model market conditions, governments explore policy implications, and even individuals can benefit from the strategic mindset fostered by these interactive experiences. The evolution from abstract military models to the dynamic, engaging RTS games of today reflects not only technological progress but also our enduring fascination with strategy, competition, and the art of overcoming adversity.

From the early, rudimentary attempts to simulate the unthinkable consequences of nuclear war to the complex, demanding worlds of modern RTS games, strategic computing has evolved into a powerful medium for both entertainment and intellectual exploration. It has transformed how we think about planning, decision-making, and the very nature of conflict, proving that sometimes, the most profound lessons can be learned by playing a game.