Long before the endless scroll of TikTok and the ubiquitous presence of Instagram filters, the internet was a nascent, often clunky, frontier. Yet, within this digital wilderness, a new form of communication was taking root: the internet meme. These seemingly nonsensical snippets of culture—often humorous, always shareable—formed the bedrock of early online communities and how we interacted in the pre-millennial digital age.

Imagine the early 1990s. The internet was a dial-up symphony of screeching modems and the faint hum of CRT monitors. Online interactions were primarily text-based, confined to bulletin board systems (BBS), Usenet groups, and nascent chat rooms. It was a world where a single ASCII art smiley face could convey a wealth of emotion.

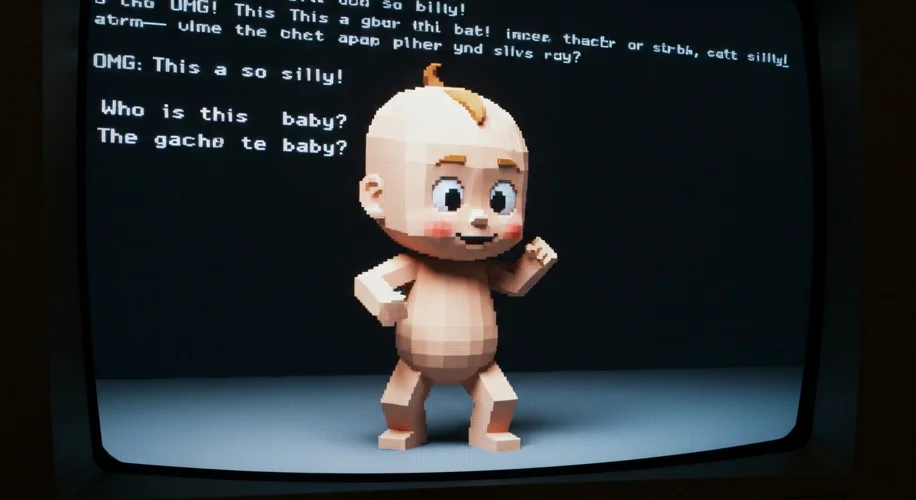

Into this world, a peculiar animation emerged that would inadvertently lay the groundwork for viral phenomena. In 1996, a computer-generated animation of a three-dimensional baby dancing to the tune of ‘Hooked on a Feeling’ by Blue Swede first appeared online. This ‘Dancing Baby,’ or ‘Baby Cha-Cha,’ as it was also known, wasn’t an intentional cultural artifact. It was a test animation created by a graphics company, but it quickly escaped the confines of its intended purpose. Shared via email and early web pages, its absurdity and simple, looping motion captivated early internet users. It became one of the first true internet sensations, a visual shorthand that transcended the text-heavy environment.

Around the same time, another digital curiosity began to take hold: the Hampster Dance. Created by a web designer named Daveedale, it featured a grid of animated hamsters dancing to a sped-up version of the song ‘Whistle Stop’ from Disney’s Robin Hood. Launched in 1998, its hypnotic, repetitive nature and the sheer, unadulterated silliness of its premise made it incredibly catchy. Users would link to the site, embedding the dancing hamsters into their own web pages, creating a chain reaction of digital delight. The simplicity was key; it was easy to consume, easy to share, and utterly disarming.

These early viral sensations were born from a different internet ecosystem. Social media platforms as we know them today did not exist. Sharing relied on email forwards, direct links on personal homepages (often built with basic HTML), and discussions in newsgroups. There were no algorithms curating content; virality was a more organic, word-of-mouth phenomenon, amplified by the novelty of the internet itself.

What made these early memes so impactful? They were a shared experience in a still-fragmented digital landscape. Discovering the Dancing Baby or sending a link to the Hampster Dance was a way to participate in a collective online culture. It was a way to signal that you were ‘in the know,’ a participant in this new digital realm. They provided a low-barrier entry point into online communication, offering a visual or auditory hook that could be understood and appreciated by many, regardless of their technical sophistication.

The impact of these early viral sensations extended beyond mere amusement. They demonstrated the nascent power of digital distribution and the potential for content to spread exponentially. They were a precursor to the sophisticated marketing and communication strategies that would later define the internet. More importantly, they highlighted the human desire for connection and shared experience, even in the abstract space of cyberspace.

These early memes were more than just fleeting digital curiosities; they were the first whispers of a revolution in communication. They taught us that in the digital age, a simple, repeatable, and relatable piece of content could achieve extraordinary reach. They were the ancestors of today’s complex meme culture, proving that even before the millennium, the internet had already begun to find its own unique, often bizarre, language. The dancing baby and the hopping hamsters, in their own innocent way, were the pioneers of a viral world that continues to shape our online lives.