The year is 2010. Deep within the Denisova Cave, nestled in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, a discovery was about to rewrite the story of human evolution. Archaeologists, meticulously sifting through layers of sediment, unearthed a tiny fragment of bone – a finger bone, to be precise. What seemed like a simple, almost insignificant find, would soon reveal itself as the key to a forgotten chapter of our ancestral past.

The bone fragment was minuscule, yielding only a small amount of ancient DNA. Yet, this was enough. Through the marvels of modern genetic analysis, scientists, led by Svante Pääbo and his team at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, detected something astonishing. The DNA bore little resemblance to that of modern humans (Homo sapiens) or even Neanderthals, our closest known extinct relatives. It was distinct, a new branch on the human family tree.

The implications were staggering. This was not just another hominin species; it was a group that had diverged from the lineage leading to Neanderthals and modern humans perhaps as early as 600,000 years ago. They were named ‘Denisovans’ after the cave where their first definitive trace was found.

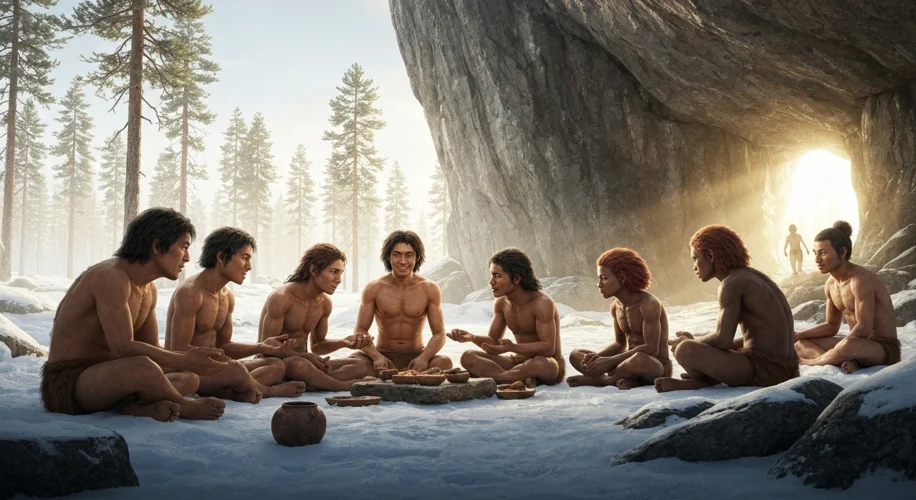

But the Denisovans were not content with remaining solely in Siberia. Further analysis of the DNA revealed that Denisovans, like Neanderthals, had ventured out of Africa and mingled with early Homo sapiens. The genetic evidence is clear: populations in Melanesia, Australia, and East Asia today carry a small percentage of Denisovan DNA, a silent testament to these ancient encounters. Imagine, for a moment, our distant ancestors, with their distinct features and ways of life, interacting with these enigmatic Denisovans. Were these encounters peaceful? Were they curious exchanges, or perhaps even conflicts? The limited fossil evidence offers few clues, leaving much to our imagination.

The Denisova Cave itself, a site of immense archaeological significance, became the focal point. It had previously yielded artifacts and remains of Neanderthals, suggesting a shared, or at least overlapping, territory with Denisovans. The cave’s cold, dry environment had, over tens of thousands of years, preserved this precious genetic information, waiting to be unlocked.

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence, beyond the initial finger bone, was the discovery of a small fragment of a mandible, or lower jawbone, found in the Baishiya Karst Cave on the Tibetan Plateau. This fossil, dated to at least 160,000 years ago, contained Denisovan DNA. Its presence at such high altitudes suggests remarkable adaptability – the ability to thrive in oxygen-poor environments, a feat that modern humans struggle with.

The story of the Denisovans is far from over. As genetic sequencing technology continues to advance, and as more ancient sites are explored, we may yet uncover more about these fascinating relatives. Were they a distinct species, or a subspecies of Neanderthals? What did they look like? What were their tools, their art, their social structures? These are the tantalizing questions that drive ongoing research.

This discovery in Denisova Cave serves as a powerful reminder of how much we still have to learn about our own past. It is a humbling realization that the human story is not a simple, linear progression, but a complex tapestry woven with the threads of many different hominin groups, each with their own unique journey. The Denisovans, once lost to time, have now re-emerged, whispering their secrets from the depths of a Siberian cave, forever altering our understanding of who we are and where we come from. The echoes of their existence resonate through our very DNA, a profound connection to a lineage we are only just beginning to comprehend.

The implications of the Denisovan discovery continue to unfold, pushing the boundaries of paleoanthropology and genetics. It highlights the dynamic nature of human evolution, a story of migration, adaptation, and interaction that spans continents and millennia.