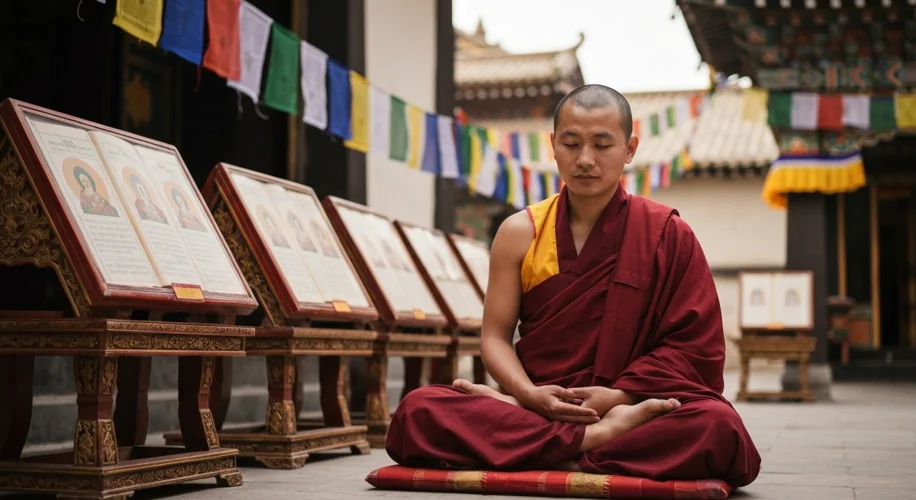

The gentle chime of temple bells, the serene chant of monks, the profound teachings of the Eightfold Path – these are the images that often come to mind when we think of Buddhism. For centuries, these spiritual and cultural currents have shaped societies across Asia. But how have these deeply ingrained traditions interacted with the modern, often turbulent, concept of democracy? It’s a question that delves into the heart of cultural identity and political evolution.

Many nations where Buddhism has been the dominant spiritual force, such as Thailand, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Bhutan, and parts of India and Nepal, have had varied and often challenging journeys toward establishing robust democratic systems. While the core tenets of Buddhism emphasize compassion, mindfulness, and non-violence, the path to translating these into stable, pluralistic governance has been far from linear.

Consider, for instance, the concept of Sangha, the monastic community. This hierarchical yet interdependent structure, with its emphasis on collective decision-making through consensus and adherence to rules, offers a unique model of social organization. Some scholars suggest that this historical experience with communal governance, albeit within a religious framework, could have laid a subtle groundwork for democratic ideals. The Sangha has traditionally served as a repository of moral authority and, at times, a check on secular power.

However, the relationship is far from simple. The historical context in many of these nations is also marked by monarchies, colonial legacies, and periods of authoritarian rule. In countries like Thailand, the monarchy, deeply intertwined with Buddhism, has often played a complex role in political stability, sometimes acting as a unifying force but also occasionally being invoked to legitimize less democratic outcomes. Similarly, Sri Lanka, despite a strong Buddhist heritage and early post-colonial democratic institutions, has grappled with ethnic tensions and civil unrest, impacting its democratic trajectory.

Myanmar (Burma) presents a particularly poignant example. Buddhism has long been central to Burmese identity, and the Sangha has historically been a powerful social force. Yet, the country endured decades of military dictatorship, a period marked by significant human rights abuses. While monks often played roles in protest movements, their engagement with the political sphere has been complex, sometimes leading to clashes with the ruling powers. The balance between spiritual devotion and civic action remains a delicate one.

In Cambodia, the legacy of the Khmer Rouge regime, which brutally suppressed religion and traditional culture, left deep scars. The subsequent rebuilding of democratic institutions has been a long and arduous process, with Buddhism playing a vital role in national reconciliation and spiritual healing, but political stability remains fragile.

Bhutan offers a different perspective. This Himalayan kingdom has undergone a unique transition from absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy, actively seeking to preserve its Buddhist culture while embracing democratic reforms. The emphasis on Gross National Happiness, a development philosophy rooted in Buddhist values, suggests a potential model for integrating spiritual and ethical considerations into governance.

What are the key actors and perspectives in this ongoing narrative? We see political leaders, religious authorities, civil society organizations, and ordinary citizens, each navigating the intersection of faith, culture, and governance. Some might argue that Buddhist principles of compassion and non-attachment are inherently conducive to democratic values, fostering an environment of tolerance and mutual respect. Others might point to the more hierarchical aspects of Buddhist traditions or the historical tendency for religious institutions to align with established powers as potential impediments.

Analyzing these historical and cultural factors reveals a nuanced picture. The concept of karma and rebirth, for instance, could be interpreted in ways that either encourage acceptance of one’s present circumstances or inspire a desire for positive change in this life to secure a better future. The emphasis on mindfulness and self-awareness could foster more considered political engagement.

Ultimately, the development of democracy in Buddhist-majority nations is not a simple cause-and-effect relationship. It is a complex interplay of historical context, cultural values, socio-economic conditions, and the choices made by individuals and institutions. While the serene path of the Buddha offers profound wisdom for personal conduct and societal harmony, its translation into the robust, pluralistic, and often messy arena of modern democracy is an ongoing, dynamic process, one that continues to unfold across Asia.

The journey is marked by a deep respect for tradition, a yearning for self-determination, and the enduring human quest for a just and equitable society, all filtered through the unique lens of Buddhist philosophy.