Imagine a time when a language, spoken by a mighty confederation of tribes, echoed across the vast plains of Europe, shaping empires and influencing the very course of history. This was the world of Gothic, an East Germanic language that, despite its initial prominence, ultimately vanished, leaving behind only whispers in the grand narrative of linguistic evolution.

Our journey begins in the 3rd century AD, a period of immense upheaval and migration. The Goths, a Germanic people, were not a single monolithic entity but a collection of tribes who had carved out a significant presence along the northern Black Sea coast and the Danube River. They were warriors, traders, and, crucially, cultural intermediaries between the declining Roman Empire and the less-understood peoples of the north.

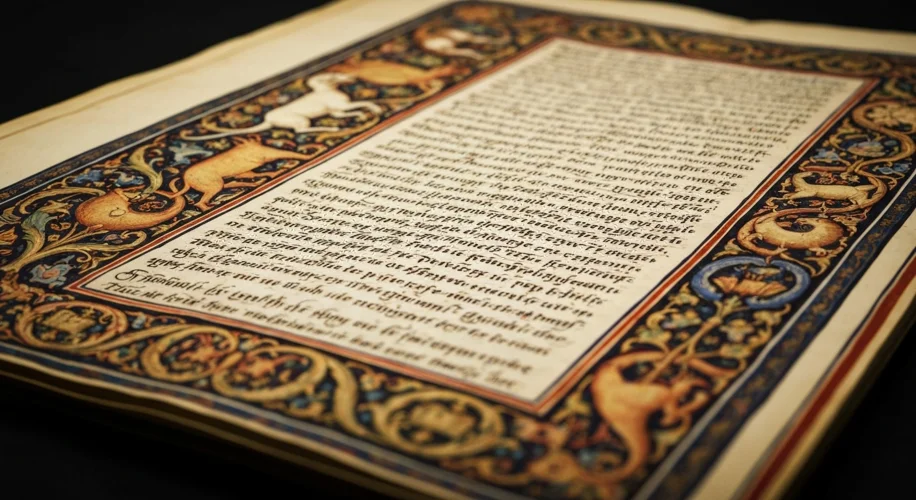

The Gothic language itself was a vibrant and expressive tongue. Its most famous literary achievement is Bishop Ulfilas’s translation of the Bible into Gothic in the 4th century. This monumental undertaking, rendered in a unique Gothic alphabet created by Ulfilas himself, provided the Goths with sacred texts in their own language, fostering a sense of shared identity and religious fervor.

“In principio erat Verbum, et Verbum erat apud Deum, et Deus erat Verbum.” So began the Gothic New Testament, a testament to the language’s sophistication and its role in disseminating Christian doctrine. This translation is our primary window into the language, preserving words and grammatical structures that would otherwise be lost to time.

But why, then, did this once-prominent language disappear? The answer lies in a complex interplay of historical forces.

The Hunnic Invasion and the Shattering of Unity: In the late 4th century, the arrival of the Huns from the East sent shockwaves through Eastern Europe. The Goths, caught in the path of this relentless migration, were fragmented. Some sought refuge within the Roman Empire, leading to events like the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD, a catastrophic defeat for the Romans. Others were pushed westward.

This dispersal, however, shattered the cohesive political and cultural entities that had nurtured the Gothic language. As Goths integrated into different societies, their language began to diverge.

The Rise of New Kingdoms and Shifting Power: The Visigoths, who established a kingdom in Hispania (modern Spain), maintained Gothic for some time. Their laws and chronicles bear the imprint of their ancestral tongue. However, the gradual Romanization of Hispania, coupled with the linguistic dominance of Latin and later Romance languages, began to erode Gothic’s vitality.

Similarly, the Ostrogoths, who established a kingdom in Italy, also used Gothic. But again, the pervasive influence of Latin, the administrative language of the region and the language of the Church, proved overwhelming. The Ostrogothic kingdom itself was eventually conquered by the Byzantine Empire, further diminishing the language’s standing.

Assimilation and Linguistic Dominance: Languages do not exist in a vacuum. They thrive through continuous use, cultural prestige, and a stable political environment. The Gothic language faced immense pressure from more dominant linguistic forces, primarily Latin and Greek, and later the burgeoning Romance and Slavic languages.

As Gothic-speaking populations mingled with and were often absorbed by larger, more linguistically entrenched groups, their unique language began to fade. Children were raised speaking the language of the majority, the language of commerce, administration, and cultural prestige. Gothic, lacking these crucial supports, slowly receded.

The Final Tapers: By the 6th and 7th centuries, Gothic was increasingly confined to smaller, more isolated communities. While some scholars believe pockets of Gothic speakers may have persisted in Crimea into the 17th or even 18th centuries, its widespread use had long since ceased. The written record, which had once offered a glimpse into its glory, fell silent.

The story of Gothic is a poignant reminder of how languages, despite their initial strength, can succumb to the tides of history, conquest, and cultural assimilation. It underscores the fragility of linguistic heritage and the powerful forces that shape the way we communicate across the ages. While Gothic itself is gone, its legacy endures in the ancient texts that preserve its memory and in the lessons it offers about the ebb and flow of human culture.