The very name conjures images of legend, of shimmering metal pulled from the depths, imbued with a mystical glow. Orichalcum. For centuries, it has existed as a whisper in the halls of history, a tantalizing enigma mentioned in the oldest texts. But was this fabled metal merely a figment of ancient imagination, or did it possess a tangible, if elusive, reality?

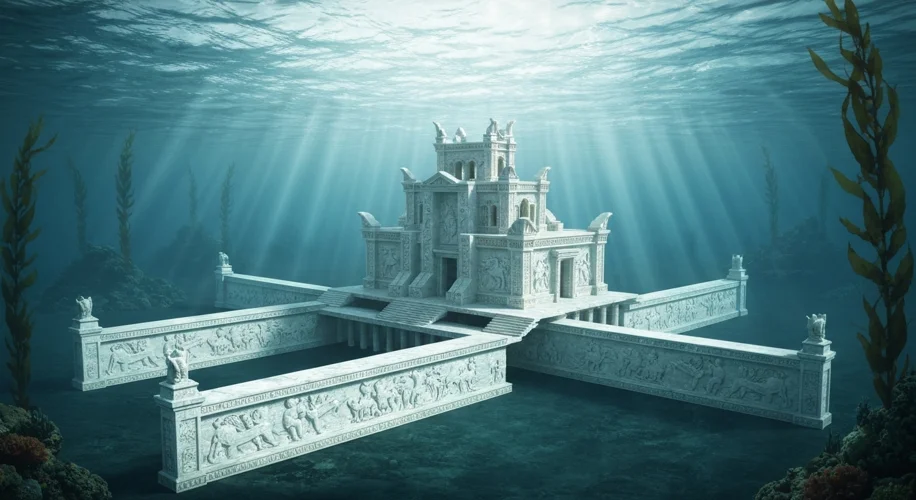

Our journey into the heart of this mystery begins not with a shipwreck, but with words etched in stone and papyrus. The earliest and most famous mention of orichalcum comes from the dialogues of Plato, specifically in his accounts of Atlantis. In the “Critias,” Plato describes the legendary island city, a marvel of engineering and opulence, its buildings adorned with the radiant metal. He wrote of walls encircling the inner citadel, one of bronze, another of tin, and the third, he claimed, “shone with a red light, like fire, and was covered in orichalcum.”

This description, penned around 360 BCE, painted orichalcum as a metal of immense value, second only to gold, used for decorative purposes and even for the awe-inspiring statues of the Atlantean gods. But Plato’s Atlantis, while captivating, has long been debated as allegory or historical fact. Was he describing a real metal, or using a fantastical element to illustrate his philosophical points about an idealized, yet ultimately doomed, civilization?

Beyond Plato, the trail of orichalcum leads us through the ancient Near East and the Mediterranean. References to a metal called urialkhum appear in Ugaritic texts dating back to the 13th century BCE, found in Ras Shamra, Syria. These texts list it as an imported commodity, suggesting it was a recognized and sought-after material, perhaps used in religious or royal contexts. The word itself, with its earthy tones, hints at a terrestrial origin, rather than something plucked from the mythical sea.

The Roman writer Pliny the Elder, writing in the 1st century CE, also discussed orichalcum. He believed it to be a metal found in ancient Greece, specifically in the region of Hades (modern-day Greece). Pliny described it as having the color of gold but being much rarer and more valuable. He suggested it was a compound metal, possibly a brass created by mixing copper and zinc, or perhaps a natural alloy.

For centuries, the prevailing theory among historians and metallurgists was that orichalcum was simply an ancient form of brass, a copper-zinc alloy. Brass has a distinct golden hue and was known to the ancients, though its production methods evolved over time. The earliest forms of brass were often accidental byproducts of smelting copper ores containing zinc. It was only later that controlled alloying became more widespread.

However, the archaeological record remained stubbornly silent on clear, undeniable examples of this “orichalcum” as described by Plato and Pliny. While ancient artifacts often feature bronze (a copper-tin alloy) and occasionally brass, nothing quite matched the legendary status and unique properties attributed to orichalcum. It remained a metal of myth, a story whispered across millennia.

Then, in 2015, a discovery off the coast of Sicily offered a tantalizing, albeit controversial, piece of the puzzle. Divers recovered a submerged cargo ship dating back to the 6th century BCE, laden with ingots of a metal alloy. Analysis revealed these ingots to be approximately 75-80% copper, 15-20% zinc, and small amounts of nickel and lead – essentially, an ancient form of brass. Crucially, the proportions of zinc in these ingots were much higher than typically found in other known ancient brass artifacts, leading some researchers to propose that these ingots might indeed be the physical manifestation of the fabled orichalcum.

This find, while exciting, did not definitively solve the mystery. Was this specific alloy, found in one shipwreck, the orichalcum of Plato’s Atlantis, or simply a particular alloy produced for a specific, perhaps localized, purpose? The debate continues. The archaeological context is crucial: this ship was carrying raw materials, not finished, ornate objects that might have been described by ancient writers.

The story of orichalcum, therefore, is a complex tapestry woven from myth, legend, and the persistent quest for tangible proof. It highlights how ancient texts, even those dealing with philosophical ideas, can sometimes point towards lost technologies or materials. While the romantic notion of a lost, shimmering metal from a sunken continent persists, the more grounded reality likely lies in the evolving understanding of ancient metallurgy. The zinc-rich brass ingots from the Sicilian wreck offer a compelling glimpse into what orichalcum could have been – a testament to the ingenuity of ancient peoples in their pursuit of materials that captured both the eye and the imagination.

Until more definitive evidence surfaces from the depths of history, orichalcum remains a powerful symbol, a reminder of the enduring allure of the unknown and the possibility that even the wildest ancient tales might hold a grain of truth.