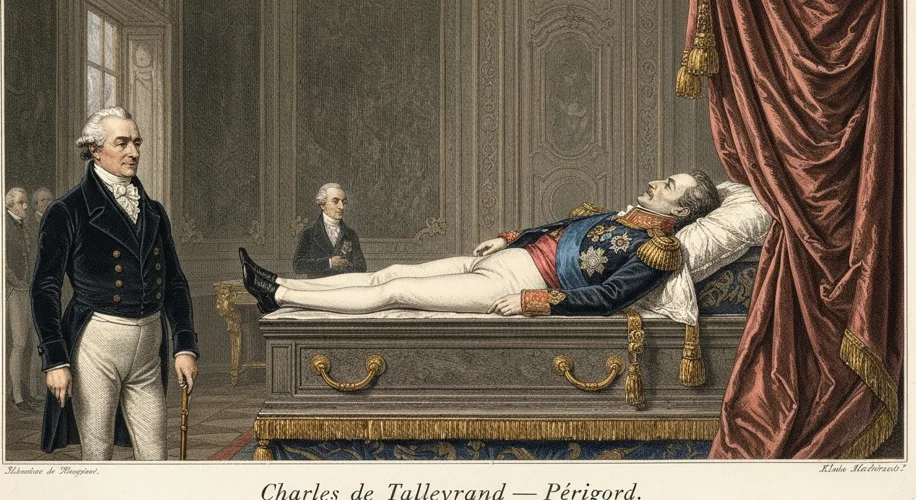

The year is 1838. In a Parisian salon, the air hung thick with the scent of expensive perfume and whispered gossip. The man at the center of this hushed drama, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, lay on his deathbed. For decades, this titan of diplomacy had navigated the treacherous currents of European politics, a chameleon who had served kings, emperors, and republics with an almost supernatural ability to survive and thrive.

Talleyrand was a paradox. Excommunicated by the Catholic Church for his earlier scandalous life, he had sought reconciliation in his final days, confessing his sins with a finality that seemed almost theatrical. Yet, even in this solemn moment, the sharpest minds of his era were reflecting on his enduring legacy. One such mind belonged to Klemens von Metternich, the architect of the post-Napoleonic European order, and a man who had often found himself on opposing sides of Talleyrand’s intricate games.

Metternich, the quintessential conservative statesman, had sparred with Talleyrand across the diplomatic battlefield for years. From the Congress of Vienna, where they meticulously redrew the map of Europe after Napoleon’s fall, to countless secret negotiations and public pronouncements, their careers were intertwined. Talleyrand, the embodiment of French resilience and cunning, and Metternich, the steadfast guardian of monarchical stability, represented two distinct, yet equally potent, forces shaping 19th-century Europe.

As the news of Talleyrand’s passing spread, Metternich, upon hearing of the former diplomat’s final, perhaps repentant, words, is said to have uttered a quip that has echoed through history: “What does he mean by that?” This seemingly simple question, however, carried the weight of Metternich’s profound understanding of Talleyrand’s complex character and his even more complex political maneuvering. Was Talleyrand truly seeking divine forgiveness, or was this a final, masterful stroke of performance, a way to shape his posthumous reputation?

Metternich, who had witnessed firsthand Talleyrand’s extraordinary ability to reinvent himself and his nation, understood that the man’s life was a testament to strategic ambiguity. Talleyrand had been a bishop, a revolutionary, a minister under Napoleon, and later, a key figure in the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. Each era demanded a different persona, a different set of principles, and Talleyrand adapted with a fluidity that astounded his contemporaries. His mastery lay not just in negotiation, but in the art of survival, in understanding the shifting sands of power and positioning himself, and France, to best advantage.

The context of their era, the aftermath of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, was one of immense upheaval. Europe had been torn apart by conflict, and the ensuing peace, largely brokered by diplomats like Metternich and Talleyrand at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, was a delicate balancing act. The goal was to restore a semblance of order and stability, to prevent another continent-wide conflagration. Both men played crucial roles in this endeavor, though their methods and ultimate aims often differed. Metternich sought to suppress liberal and nationalist movements, fearing they would destabilize the established order. Talleyrand, while a royalist at heart, understood the need for France to adapt to the new realities, often advocating for policies that secured French influence without resorting to overt aggression.

Metternich’s quip, therefore, was not merely a comment on a deathbed confession. It was a reflection on a lifetime of calculated ambiguity. Talleyrand’s final moments, much like his entire career, offered an opportunity for interpretation, for the continuation of the subtle games he had played so masterfully. Was his final utterance a genuine plea for salvation, or a final, ironic nod to the enduring mystery of his life and the man himself? For Metternich, the question remained, and perhaps, in the grand theatre of European diplomacy, the answer was less important than the enduring power of the question itself.

Talleyrand’s death marked the end of an era, the passing of a diplomat whose influence stretched across revolutions and restorations. Metternich’s pithy response served as a fitting, if somewhat sardonic, epitaph for a man who had spent his life mastering the art of the unsaid, leaving behind a legacy as complex and enigmatic as his final words.