The summer of 1858 dawned like any other in London, but it would soon become a summer that the city would never forget – and certainly never want to repeat. A suffocating, putrid stench descended upon the capital, a miasma so foul it threatened to bring the great city to its knees. This wasn’t the smell of industry or combustion, but something far more primal and pervasive: the stench of raw sewage, hundreds of thousands of tons of it, fouling the very artery of London – the River Thames.

For centuries, London had grown, spilling its waste directly into the river that had sustained it. The Thames, once a source of life and commerce, had become an open sewer. By the mid-19th century, a burgeoning population of over two million people, coupled with industrialization, had transformed the river into a toxic brew. The city’s rudimentary sewer system, a patchwork of aging brickwork and open channels, was overwhelmed. Waste, along with rainwater, flowed directly into the Thames, only to be carried downstream, only to be pumped back up into people’s homes via unreliable water systems. It was a grim, cyclical contamination.

The conditions were dire, but it was the unseasonable heatwave of that summer that turned a chronic problem into an acute crisis. The high temperatures caused the exposed mudbanks of the Thames, now thick with human and animal waste, to ferment and putrefy. The smell was unbearable. Parliament, situated right on the riverbank, was particularly afflicted. Curtains were soaked in chloride of lime, a desperate attempt to mask the overwhelming odor, but even this chemical deterrent proved futile against the sheer intensity of the stench. Members of Parliament found it impossible to conduct business, fleeing their chambers in disgust. One legislator famously declared, “The House is uninhabitable.” Queen Victoria herself was forced to cancel a royal excursion on the Thames due to the noxious fumes.

The “Great Stink,” as it came to be known, was more than just an unpleasant olfactory experience; it was a stark, undeniable public health emergency. Cholera epidemics had already ravaged London in previous decades, and the putrid river was a breeding ground for disease. The stench was a constant, visceral reminder of the unseen killer lurking in the water supply. Doctors and sanitation reformers had long warned of the dangers of the untreated sewage, but it took this overwhelming assault on the senses to galvanize action.

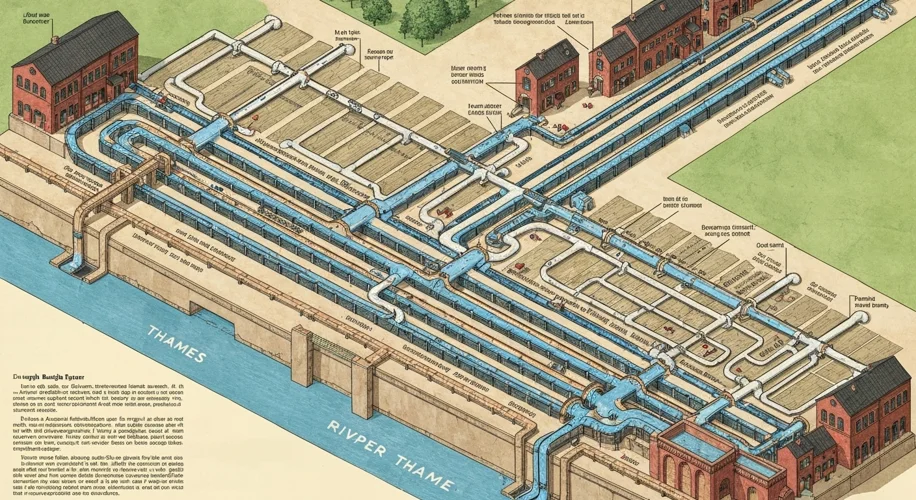

The crisis finally forced the hand of the government. Sir Joseph Bazalgette, a brilliant engineer, had already proposed a comprehensive solution: a vast, ambitious new sewer system that would intercept the city’s waste and carry it far downstream, away from the metropolis, before discharging it into the estuary. His plan involved an intricate network of intercepting sewers running parallel to the Thames, with pumping stations to lift the sewage over higher ground. The sheer scale of the project was staggering, requiring miles of tunnels, massive construction efforts, and significant financial investment. The Great Stink, however, provided the political will and public mandate to push Bazalgette’s vision forward.

Work began in 1859, and over the next two decades, Bazalgette and his teams constructed over 80 miles of major intercepting sewers and over 1,000 miles of street sewers. This monumental undertaking transformed London’s sanitation, drastically reducing waterborne diseases like cholera and typhoid. The river, once a fetid open drain, began to recover. The project also spurred innovations in public health policy and urban planning, setting a precedent for tackling similar challenges in other rapidly growing cities worldwide.

The Great Stink serves as a potent historical lesson. It reminds us that the foundations of modern, healthy cities are often laid in the most unglamorous, yet essential, infrastructure. It was an event born of neglect and overwhelming public health crisis, but it ultimately led to one of the most significant public works projects in history, a subterranean marvel that continues to serve London to this day. The foulest hour for London was, paradoxically, the dawn of a new era of sanitation and public health, forever changing the way cities manage their waste and protect their citizens.