In the annals of history, few diseases have captured the cultural imagination quite like tuberculosis, often referred to as ‘consumption.’ Far from being solely a harbinger of death, consumption, especially during the 18th and 19th centuries, became intertwined with notions of beauty, artistic sensitivity, and even spiritual transcendence. This paradox – the romanticization of a deadly illness – offers a fascinating lens through which to view societal values, artistic expression, and the human struggle against mortality.

The Shadow of the White Plague

For centuries, tuberculosis ravaged populations, a relentless scourge that left no social strata untouched. Its insidious nature, slowly wasting the body, often manifested in a range of symptoms that, to the Victorian and Romantic eye, could be misconstrued as signs of profound depth and ethereal beauty. A pale complexion, a delicate frame, rosy cheeks (often a sign of fever), a hacking cough, and a heightened emotional state were frequently associated with the disease. These were the very traits that artists and writers began to champion as the pinnacle of sensitivity and refined existence.

From Sickness to Symbolism

The shift from viewing consumption as purely a disease to a symbol of artistic suffering was gradual but profound. The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and order had, in some circles, given way to the Romantic movement’s celebration of emotion, individualism, and the sublime. In this context, the physical frailty caused by tuberculosis became a metaphor for a sensitive soul overwhelmed by the world’s harsh realities. The afflicted individual was seen as existing on a higher plane, their suffering a conduit for profound insight and creative genius.

Consider the works of John Keats, a poet who himself succumbed to tuberculosis at the young age of 25. His poetry, filled with exquisite imagery and a deep sense of longing, is often imbued with a melancholic beauty that resonates with the very essence of the romanticized consumptive. His famous line, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know,” from “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” speaks to a Platonic ideal that many associated with the consumptive’s perceived spiritual clarity.

Similarly, the French novelist George Sand, in her semi-autobiographical works, often depicted characters whose tuberculosis was linked to artistic temperament and emotional vulnerability. Frédéric Chopin, Sand’s lover, was a renowned composer whose delicate health and profound musicality were often discussed in the same breath as his struggle with the disease.

The Consumptive Archetype in Literature and Art

This romantic ideal manifested in numerous literary characters. In Alexander Dumas’s La Dame aux Camélias, the courtesan Marguerite Gautier, dying of consumption, is portrayed with a tragic beauty and an enduring capacity for love. Her illness serves not only as a plot device but also as a marker of her refinement and deep emotional capacity. The opera La Traviata, based on Dumas’s novel, further cemented this image in the public consciousness.

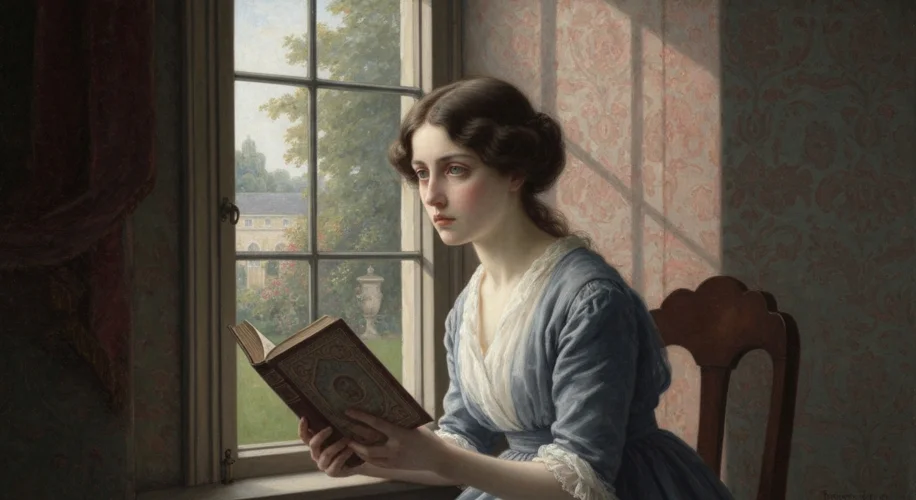

Even in visual arts, the pale, ethereal beauty associated with consumption became a desirable aesthetic. Pre-Raphaelite painters, with their focus on detailed, often melancholic or romantic subjects, sometimes depicted figures that echoed this aesthetic. The delicate features, the flowing hair, and the often-sad expressions were part of a larger artistic vocabulary that intertwined illness with a certain kind of beauty.

Why the Romanticization?

Several factors contributed to this cultural phenomenon:

- Association with Artistic Genius: The perceived link between heightened sensitivity, suffering, and artistic output led to the belief that consumption somehow enabled creativity.

- Escape from Mundanity: In a world that could be seen as increasingly industrialized and materialistic, the consumptive’s perceived spiritual depth offered an escape, a focus on inner life.

- Social Mobility and Status: For some, the delicate nature associated with consumption might have been a way to distance oneself from manual labor and project an image of refinement or aristocracy, even if ironically.

- The Inevitability of Death: Facing a disease with no cure, people often sought meaning and beauty in the face of death. Romanticism, with its focus on emotion and the sublime, provided a framework for this.

The Darker Side of the Myth

It is crucial to remember that this romanticization masked a brutal reality. For those suffering from tuberculosis, there was no inherent beauty in the debilitating pain, the isolation, or the often-agonizing death. The romantic image served as a coping mechanism, a way for society to frame and distance itself from a terrifying disease. It allowed for an aesthetic appreciation of suffering that was ultimately detached from the lived experience of the patient.

As medical understanding advanced and treatments for tuberculosis began to emerge in the 20th century, the romantic allure of consumption faded. The advent of antibiotics like streptomycin offered a tangible hope and a cure, stripping the disease of its mystique. Yet, the echoes of this cultural fascination remain, a testament to how deeply art, literature, and society can weave together life, death, and beauty in the most unexpected of ways.

The romanticization of consumption is a complex historical thread, revealing a society grappling with mortality, seeking meaning in suffering, and finding beauty in the most unlikely of places. It reminds us that culture is not merely a reflection of reality, but an active interpretation, capable of transforming even the most devastating of illnesses into potent symbols.