Imagine a world painted in muted greens and browns, teeming with life forms that defy our modern imagination. This was Earth, half a billion years ago, during the Cambrian period. It was an era of explosive evolutionary innovation, a time when the blueprint for most of the animal kingdom was being sketched out. Yet, for all the wonders of this ancient epoch, direct evidence of its inhabitants’ inner workings has been frustratingly scarce. Until now.

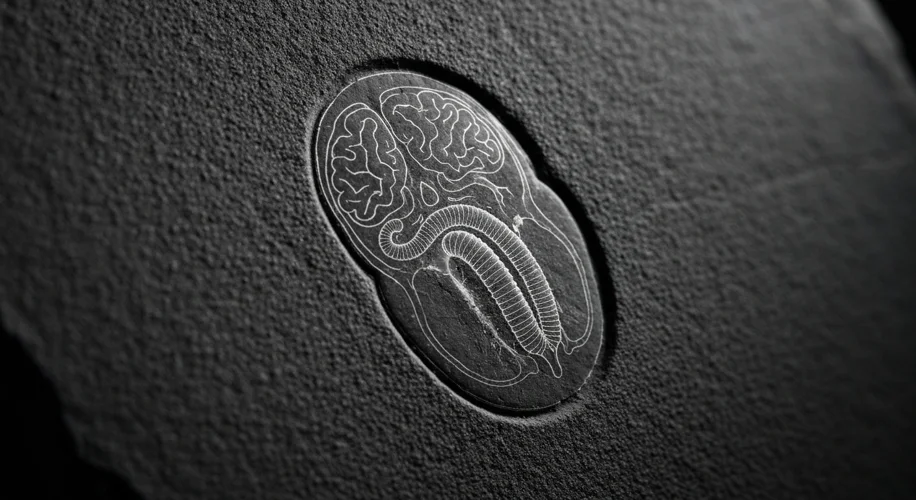

In a discovery that has sent ripples of excitement through the scientific community, researchers have unearthed a fossil from the Cambrian period, approximately 500 million years old, that boasts an almost unbelievable level of preservation. This isn’t just another fossilized shell or bone; this specimen has yielded perfectly preserved soft tissues, including an intact brain and digestive system. Such finds are akin to finding a pristine message in a bottle from the dawn of complex life, offering an unparalleled glimpse into the anatomy and biology of creatures that swam Earth’s primordial seas.

The sheer rarity of fossils with preserved soft tissues, especially for an era as ancient as the Cambrian, cannot be overstated. Most life from this period has left behind only mineralized hard parts. The forces of fossilization are notoriously selective, typically favoring durable materials like bone and shell over the delicate, easily degraded tissues that make up brains and guts. For such soft tissues to survive for half a billion years requires an extraordinary confluence of geological and chemical conditions. Imagine an animal dying in an environment with extremely low oxygen, perhaps rapidly buried in fine, anoxic sediment, preventing scavengers and decomposers from obliterating its delicate internal structures. This rapid burial and lack of oxygen act as a natural preservative, allowing soft tissues to fossilize under specific circumstances.

This particular discovery is significant not only for the preservation of these vital organs but also for the information they contain. The brain, the control center of any animal, reveals crucial details about the sensory capabilities and nervous system complexity of this ancient creature. The digestive system, a testament to its feeding habits and metabolic processes, paints a picture of its place in the Cambrian food web. Scientists can now study the intricate pathways of its gut, inferring what it ate and how it processed nutrients, offering a direct window into its ecological niche.

While the specific identity of the creature is still under detailed analysis, the implications are vast. This fossil could belong to an arthropod, a group that dominated the Cambrian seas and includes ancestors of modern insects, spiders, and crustaceans. The preservation level might even allow for insights into the musculature and appendage articulation, providing data that could refine our understanding of Cambrian locomotion and predator-prey dynamics.

The study of such fossils is a detective game played across geological time. Each detail, from the cellular structure of the preserved tissues to the geological context of the find, is meticulously analyzed. Scientists use advanced imaging techniques, such as synchrotron X-ray microscopy, to peer into the fossil without damaging it, revealing structures that are invisible to the naked eye. This allows them to reconstruct not just the form, but potentially the function of these long-extinct beings.

Ultimately, this remarkable 500-million-year-old fossil serves as a powerful reminder of life’s incredible journey. It pushes back the boundaries of our knowledge, offering tangible proof of the intricate biological machinery that was already in place during the formative stages of animal evolution. It’s a testament to the enduring power of natural processes and the relentless curiosity of science, allowing us to connect, in a very real sense, with the ancient inhabitants of our planet and understand the deep roots of the life we see today.