The dim, flickering lamplight cast long, dancing shadows across the adobe walls of Peter Maxwell’s home in Fort Sumner, New Mexico. It was the night of July 14, 1881. The air was thick with the scent of dust and anticipation. John Henry “Billy the Kid” McCarty, a name that had become synonymous with both daring outlawry and youthful rebellion, was a captive. He had been apprehended by Sheriff Pat Garrett, a man who knew him perhaps too well, having once been his friend.

Billy, clad in his familiar dusty clothes, was seemingly cornered. The legend of his supposed 21 killings—one for each year of his short, tumultuous life—preceded him. He had escaped from jail just days before, a feat as audacious as any of his previous exploits. Now, he found himself in a familiar predicament, awaiting a fate that seemed to be closing in like the New Mexico night.

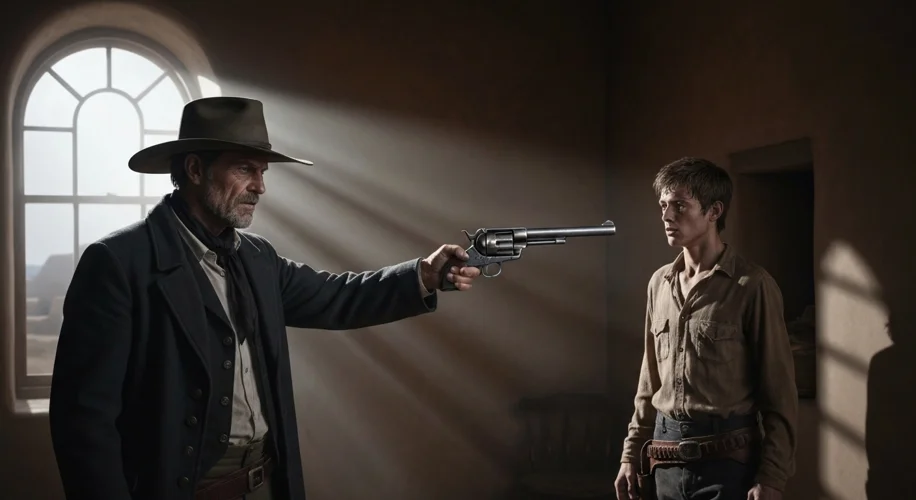

Garrett, alerted by Maxwell to Billy’s presence in the house, entered the darkened room where the Kid was being held. Billy, unarmed and disarmed, was pacing. Accounts differ on the exact sequence of events, but the most enduring detail, the one that has echoed through the decades, is the Sheriff’s chilling question.

As Garrett stepped into the room, Billy, perhaps sensing an imminent threat or hearing a floorboard creak, turned. In the semi-darkness, he couldn’t quite make out the figure. It was then, according to Garrett’s own account in his book “The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid,” that the Kid uttered his last words: “¿Quién es?” – “Who is there?” in Spanish.

This seemingly simple question, delivered in a language that held a deep connection to the Southwest, has fueled endless debate and speculation. Why Spanish? Billy the Kid, born Henry McCarty, was of Irish and possibly English descent, though he was known by various aliases. His early life was spent in New York, then he moved west, his path eventually leading him to the Spanish-speaking communities of New Mexico. It was in these communities that he found refuge, forged alliances, and, crucially, adopted the Spanish language.

His life in New Mexico was deeply intertwined with the Hispanic culture. He rode with Hispanic cowboys, learned their ways, and, it’s believed, spoke their language. For Billy, Spanish wasn’t just a foreign tongue; it was a language of his adopted home, a language of camaraderie and survival. It was the language of many of the people he knew, fought alongside, and perhaps even stole from. It was the language of the frontier itself, a melting pot of cultures.

When Garrett, the imposing figure of the law, entered that room, Billy’s immediate instinct, his deepest ingrained response to an unknown presence in a potentially dangerous situation, was to use the language that felt most natural, most connected to his experiences in this land. It was a moment of raw instinct, a whisper of his life lived on the fringes of American society, deeply embedded within the Hispanic fabric of New Mexico.

Garrett’s response was immediate and fatal. He fired his pistol twice. The first shot struck Billy in the chest, and the second, as he fell, reportedly hit him in the throat. Billy the Kid, the young outlaw whose legend was already larger than life, was dead.

Was Billy’s use of Spanish a sign of comfort, a reflection of his deepest connections, or simply a linguistic habit formed by years spent among Spanish speakers? Some historians argue it was a testament to his assimilation into the local culture, a genuine expression of belonging in a land that had become his true home, however brief. Others see it as purely opportunistic—a learned phrase to perhaps disarm or confuse his captor, even in his final moments.

Regardless of the precise motivation, the image of Billy the Kid, a figure of Anglo-American legend, uttering his last words in Spanish is profoundly evocative. It paints a picture of a complex individual, a product of the brutal, multi-cultural frontier. It reminds us that the romanticized image of the lone gunman often obscures the intricate web of cultural exchange and adaptation that defined the American West.

Billy the Kid’s final question, a simple phrase in a foreign tongue, became a powerful symbol. It encapsulated his life on the borderlands, his immersion in a culture not his own, and the poignant reality of his end. It was a moment where legend met the gritty truth of a life lived and lost on the vast, untamed plains of New Mexico, forever leaving us to ponder the meaning behind his very last words.