Imagine a time, thousands of years ago, before written records, before cities, before even the concept of nationhood as we know it. Yet, from the mists of prehistory, a powerful current flows through countless languages spoken today, from the sun-drenched shores of the Mediterranean to the windswept plains of India, and across the vast Atlantic to the Americas. This current is the legacy of a single, ancestral language: Proto-Indo-European, or PIE.

For ordinary folks interested in history, the very idea of a language spoken by people who left no written testament can seem like pure conjecture, a fascinating but ultimately unprovable theory. However, the existence of PIE is not a matter of blind faith among historians and linguists; it is a conclusion reached through meticulous, evidence-based reconstruction, a detective story played out across millennia.

The journey to uncovering PIE began not with ancient texts, but with a startling observation made in the late 18th century. Sir William Jones, a British judge and scholar in India, noticed uncanny similarities between Sanskrit, the classical language of India, and Latin and Greek, the foundational languages of Western civilization. He famously remarked that these languages, however different, must have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.

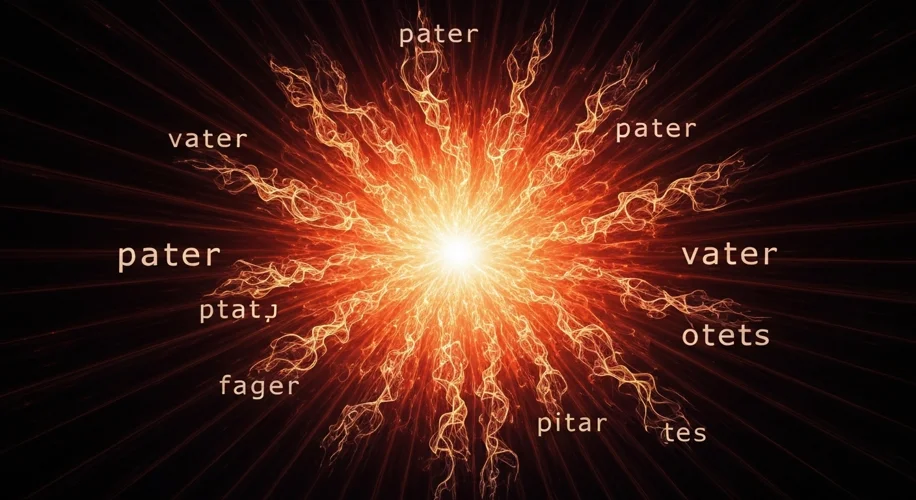

This wasn’t just a casual observation. Jones was like a linguist’s Sherlock Holmes, piecing together clues. He saw shared roots for words like ‘pater’ (father) in Latin, ‘pitr’ in Sanskrit, and ‘patēr’ in Greek. The resemblance was too profound to be accidental. This realization ignited a scholarly pursuit that would span centuries, involving some of the most brilliant minds in philology.

How do you reconstruct a language that has no speakers, no texts, no monuments? The method is known as the comparative method. Linguists like Franz Bopp, Jacob Grimm (yes, the Brothers Grimm of fairy tale fame), and later, August Schleicher, began systematically comparing related words and grammatical structures across different Indo-European languages. They looked for patterns of sound change – predictable shifts in pronunciation over time.

For instance, if a ‘p’ sound in one language consistently corresponded to a ‘f’ sound in another, and an ‘s’ sound corresponded to a ‘h’, they could work backward. By applying these reconstructed sound laws, they could hypothesize what the original PIE word might have sounded like. The process is akin to forensic reconstruction, where fragmented bones tell the story of a complete skeleton.

What did this reconstructed language look like? PIE is thought to have been spoken roughly between 4500 and 2500 BCE. Its speakers, often referred to as the “Proto-Indo-Europeans,” are believed to have originated somewhere in the Pontic-Caspian steppe, an area of grasslands north of the Black Sea.

Their culture, as inferred from the reconstructed vocabulary, was surprisingly sophisticated. They had words for family relations (mother, father, brother, sister), for domesticated animals (cattle, sheep, horses), for farming tools, for wheeled vehicles, and even for concepts like ‘god’ and ‘king’. The presence of words for ‘horse’ and ‘wheel’ is particularly significant, suggesting their role in early mobility and warfare.

The most widely accepted theory for the spread of PIE and its daughter languages is the Kurgan hypothesis, proposed by archaeologist Marija Gimbutas. She linked the expansion of Indo-European speakers with the proliferation of Kurgan (burial mound) culture from the steppes. As these people migrated, their language spread, diverging into various branches: Germanic, Italic (leading to Latin and Romance languages), Celtic, Slavic, Baltic, Indo-Iranian, Greek, Armenian, and others.

Let’s look at a concrete example. The PIE word for ‘father’ is reconstructed as ‘*ph≒ter.’ From this single root, we get ‘pater’ in Latin (father of Rome), ‘father’ in English, ‘vater’ in German, ‘otets’ in Russian, ‘pater’ in Greek, ‘baba’ in some Slavic languages, and ‘pitar’ in Sanskrit. The list goes on, a testament to a shared linguistic ancestry.

The impact of PIE is immeasurable. It is the bedrock upon which much of Western and Indian civilization was built, linguistically speaking. Understanding PIE allows us to trace the migrations of ancient peoples, reconstruct their social structures, and even gain insights into their worldview. It’s a powerful tool for understanding the deep, often invisible, connections that bind humanity together.

While the exact homeland and the precise mechanisms of its spread are still debated among scholars, the existence of Proto-Indo-European is a cornerstone of modern linguistics and historical studies. It’s a triumph of human intellect, a testament to our ability to reconstruct the past through careful analysis and a deep appreciation for the enduring power of language.