In the mid-20th century, a powerful psychoactive compound, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), emerged from the shadows of laboratory experiments and stepped onto a world stage poised for transformation. Initially hailed as a potential breakthrough in psychotherapy, its journey has been a tumultuous one, marked by societal upheaval, widespread prohibition, and a recent, surprising resurgence of scientific interest.

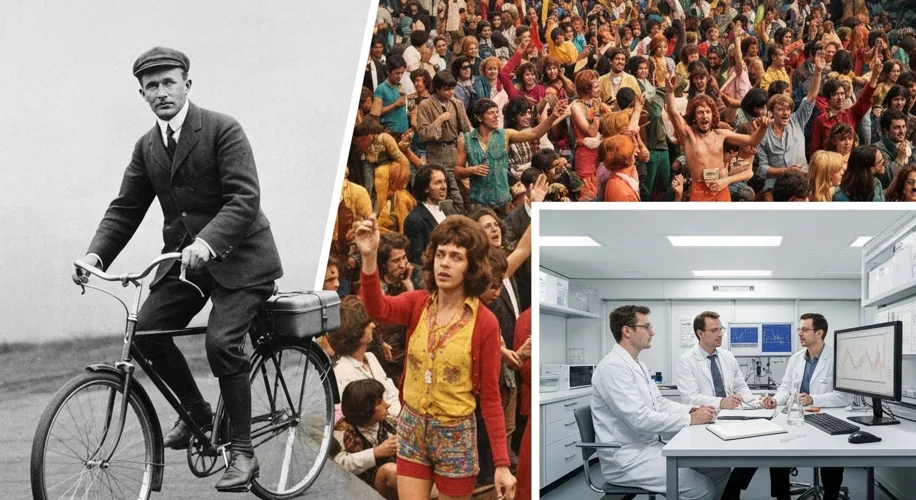

It all began in 1938 in the laboratories of Sandoz Pharmaceuticals in Basel, Switzerland. Albert Hofmann, a chemist, was synthesizing various compounds derived from ergot, a fungus that grows on rye. While his initial attempts didn’t yield the desired medicinal properties, Hofmann set the compound aside. It wasn’t until March 1943, during a period of intense research prompted by wartime needs, that Hofmann revisited lysergic acid diethylamide. Driven by a hunch, he synthesized it again, and a few days later, on April 16th, he accidentally ingested a small amount. The experience was profound: a vivid, almost hallucinatory state that left him with a sense of wonder and disorientation. Three days later, on April 19th, now famously known as “Bicycle Day,” Hofmann deliberately consumed a larger dose, intending to replicate the effect. He rode his bicycle home from the lab, accompanied by his wife, Anya, experiencing an extraordinary journey through altered perceptions and intense emotional states. This marked the first intentional human exploration of LSD’s mind-altering capabilities.

The potential therapeutic applications of LSD quickly captured the attention of the psychiatric community. In the 1950s and early 1960s, a wave of optimism swept through research institutions. Psychiatrists and psychologists explored LSD’s ability to induce states of introspection and emotional release, believing it could unlock repressed memories and facilitate breakthroughs in treating conditions like alcoholism, depression, and anxiety. Studies were conducted at institutions like Harvard University, where Dr. Timothy Leary and Dr. Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass) explored LSD’s effects on consciousness, albeit with methods that would later be criticized for their lack of rigorous control.

Dr. Humphry Osmond, a British psychiatrist, coined the term “psychedelic” – meaning “mind-manifesting” – to describe the experience induced by LSD and similar compounds. He envisioned these substances as tools that could, under controlled conditions, offer profound insights into the human psyche. Early research suggested promising results. A 1958 study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry by Dr. Maxwell R. Katz and colleagues reported that LSD could be beneficial in treating chronic alcoholism, with patients experiencing significant improvements after just one or two sessions.

However, the escalating use of LSD outside of therapeutic settings began to cast a long shadow. The burgeoning counterculture movement of the 1960s embraced LSD as a symbol of rebellion, exploration, and liberation from societal norms. Figures like Timothy Leary became prominent advocates, famously proclaiming, “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” This widespread, often uncontrolled, recreational use, coupled with sensationalized media reports of “bad trips” and perceived societal disruption, fueled public fear and ignited calls for prohibition.

The turning point came in 1966 when LSD was made illegal in the United States. This was followed by its classification as a Schedule I drug by the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances in 1971, effectively halting most legitimate research. The scientific community, once enthusiastic, largely abandoned the study of LSD due to legal restrictions and the prevailing stigma. For decades, LSD was primarily associated with the excesses of the counterculture, its therapeutic potential relegated to the realm of myth and controversy.

But as history often shows, ideas that are suppressed can, and often do, resurface. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a new generation of researchers, often working with limited funding and in defiance of lingering stigmas, began to re-examine LSD and other psychedelics. Advances in neuroscience and imaging technologies provided new tools to understand how these compounds interact with the brain.

Today, the landscape is shifting dramatically. Clinical trials are once again exploring the potential of LSD-assisted therapy. Organizations like the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) and the Beckley Foundation are at the forefront of this research. Early results from these contemporary studies are encouraging, mirroring some of the positive findings from the pre-prohibition era, but with far more rigorous methodologies. For instance, a 2021 study published in the journal Cell by researchers at the University of Zurich demonstrated that low doses of LSD could reduce anxiety and improve mood without inducing significant perceptual changes, suggesting a potential for microdosing in therapeutic contexts.

The renewed interest in LSD is not merely academic. It’s driven by a pressing need for innovative treatments for mental health conditions that often resist conventional therapies. The potential of psychedelics to facilitate profound psychological change, even after just a few sessions, offers a glimmer of hope for individuals struggling with conditions like treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, and end-of-life anxiety. While challenges remain, including navigating regulatory hurdles and ensuring responsible implementation, the journey of LSD from a stigmatized substance to a potential therapeutic agent represents a compelling chapter in the ongoing quest to understand and heal the human mind.