The scent of smoke and despair still clung to the air in 1945. Europe, a continent ravaged by six years of brutal conflict, lay in ruins. Cities were pockmarked with craters, landscapes scarred, and millions of lives irrevocably altered. In the wake of such unprecedented destruction, a profound question echoed through the shattered halls of power: how could such a cataclysm ever be prevented again?

The answer, forged in the crucible of post-war necessity and a desperate yearning for lasting peace, lay not in retribution, but in integration. This wasn’t a sudden revelation, but a slow, deliberate unfolding of an idea that had simmered for decades: the concept of a united Europe.

Long before the horrors of World War II, visionaries had dreamt of a continent free from the cyclical bloodshed that had defined its history. Thinkers like Victor Hugo, in the mid-19th century, had spoken of a “United States of Europe,” a bold prediction of a future where nations, once locked in perpetual rivalry, would coexist in harmony. These were not mere idle fantasies; they were potent seeds planted in the fertile ground of intellectual discourse, waiting for the right historical moment to sprout.

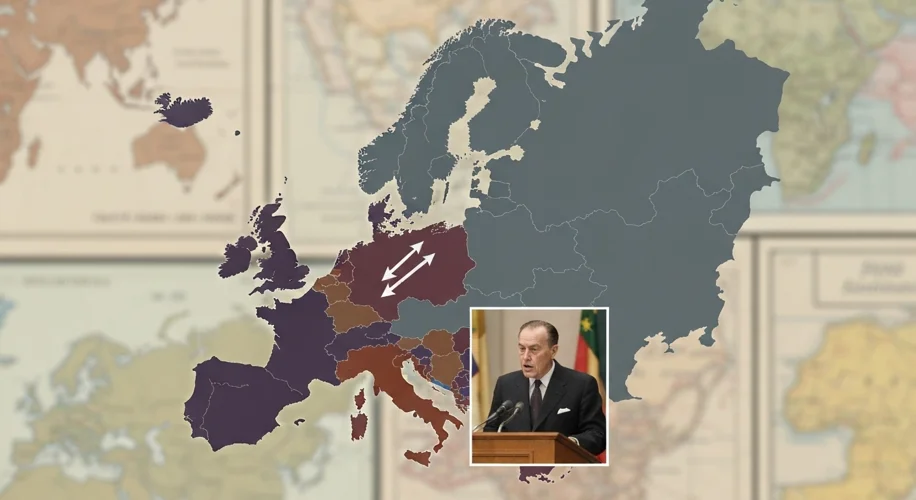

The immediate aftermath of World War II provided that moment. The old order had crumbled, leaving a vacuum and a stark realization: the intense nationalism that had fueled the war was a dangerous, destructive force. Leaders across a war-weary continent began to explore radical new paths. Among the most instrumental figures was Robert Schuman, the French Foreign Minister. On May 9, 1950, Schuman, echoing the sentiments of his German counterpart Konrad Adenauer, proposed a plan that would fundamentally alter the course of European history.

Schuman’s declaration, now celebrated as Europe Day, was deceptively simple in its stated aim: to make war between historic rivals France and Germany “not merely unthinkable, but materially impossible.” The mechanism? To pool their coal and steel resources under a common High Authority, an entity that would oversee these vital industries, crucial for any nation’s war-making capacity. It was a stroke of diplomatic genius, a pragmatic step towards political unity disguised as an economic agreement.

This bold proposal led to the Treaty of Paris in 1951, establishing the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). It was a small step, perhaps, but a giant leap in concept. Six nations – France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg – committed to this groundbreaking venture. Their motivations were complex: West Germany sought legitimacy and integration into the Western bloc, France aimed to manage and contain its traditional rival, while the smaller nations saw an opportunity to regain influence and secure economic stability.

But the ECSC was just the beginning. The embers of integration, once fanned, began to glow brighter. The success of the ECSC spurred discussions about deeper economic ties. This led to the Treaty of Rome in 1957, which created the European Economic Community (EEC), often referred to as the “Common Market.” This treaty aimed to create a single market where goods, services, capital, and people could move freely across national borders, dismantling trade barriers and fostering unprecedented economic cooperation.

Imagine the scene: border crossings, once fraught with checks and bureaucracy, slowly becoming relics of the past. The “four freedoms” – free movement of goods, services, capital, and persons – became the bedrock of this new European order. This was a radical departure from the fragmented, protectionist policies that had often defined European trade for centuries.

The 1960s and 1970s saw the EEC grow, with new member states joining its ranks, each seeking to benefit from this burgeoning economic powerhouse. Yet, the path was not always smooth. Internal disagreements, economic downturns, and the lingering specter of nationalism presented significant challenges. The expansion of the community also brought its own set of complexities, as diverse national interests needed to be harmonized.

The late 20th century witnessed a further acceleration of integration. The Single European Act in 1986, for instance, was a crucial step in completing the single market, removing the remaining obstacles to free movement. But the most significant transformation was yet to come. The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union opened up new horizons. The prospect of reunifying Europe, both geographically and politically, was now within reach.

This momentous shift culminated in the Maastricht Treaty, signed in 1992 and effective from 1993. This treaty officially established the European Union (EU), transforming the EEC into a much broader entity. It laid the groundwork for a common currency, the Euro, and introduced closer cooperation in areas like foreign policy, security, and justice. The EU was no longer just an economic project; it was aspiring to be a political union, a community of shared values and common destiny.

The expansion in the late 20th century was particularly dramatic, drawing in countries from Central and Eastern Europe that had, for decades, been under Soviet influence. This was a powerful symbol of liberation and a testament to the enduring appeal of the European project. It represented the fulfillment of Schuman’s original vision, extending the embrace of peace and prosperity to a continent long divided by the Iron Curtain.

The motivations behind this ongoing integration were manifold. For many nations, it was an assurance of security in a volatile world. For others, it was an economic engine, driving prosperity and creating opportunities. Crucially, it was also a conscious rejection of the past, a collective commitment to building a future where dialogue and cooperation would triumph over conflict and division. The history of the European Union, from its tentative post-war beginnings to its expansion at the close of the 20th century, is a compelling narrative of human resilience, pragmatic idealism, and the enduring pursuit of peace.