In the annals of human history, few inventions have resonated with the power to reshape societies quite like the printing press. Imagine a world where books were precious, painstakingly copied by hand, accessible only to the elite. This was the reality for centuries. Then, around 1440, in the heart of Mainz, Germany, a goldsmith named Johannes Gutenberg tinkered with a revolutionary idea that would shatter this exclusivity and unleash an unprecedented flood of knowledge.

Before Gutenberg, the written word was a luxury. Monks in scriptoriums dedicated their lives to the laborious task of illuminating manuscripts, a process that could take years for a single volume. The result was that books were rare, expensive, and often guarded within the cloistered walls of monasteries or the opulent libraries of royalty and wealthy merchants. Literacy was a privilege, and the dissemination of ideas was a slow, trickle-down affair. The vast majority of the population remained locked in a world where information was primarily oral, subject to the whims of memory and interpretation.

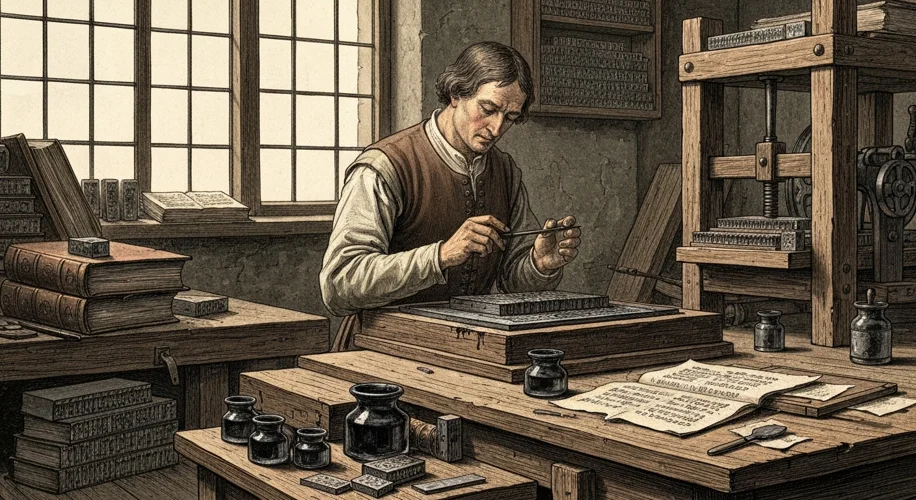

Gutenberg, a man of meticulous craftsmanship and relentless curiosity, was not the first to conceive of movable type. The concept had originated in East Asia centuries earlier, with Chinese and Korean artisans experimenting with ceramic and metal characters. However, these systems were often cumbersome, dealing with thousands of distinct characters for complex writing systems. Gutenberg’s genius lay in adapting and refining existing technologies, particularly those of metallurgy and the wine press, to create a practical and efficient system for the Latin alphabet. He developed a method for mass-producing uniform metal type, an oil-based ink that adhered well to metal, and a press that could apply even pressure to transfer the ink to paper or vellum. This combination was the true revolution.

The year 1455 is often cited as a pivotal moment, the year Gutenberg completed his masterpiece: the Gutenberg Bible. This wasn’t just any Bible; it was a testament to his innovation. Each page was a marvel of consistency, far surpassing the variations inherent in hand-copied texts. The crisp, uniform letters, the balanced layout – it was a product of precision engineering. The production of the Bible was a monumental undertaking, requiring thousands of individual type pieces, vast quantities of paper, and immense skill.

The impact of Gutenberg’s invention was nothing short of seismic. Suddenly, the cost and time required to produce books plummeted. Information, once a guarded treasure, began to flow like a river. The printing press became the engine of the Renaissance, accelerating the spread of classical knowledge and new discoveries. It fueled the Protestant Reformation; Martin Luther’s Ninety-five Theses, once a local grievance, were printed and distributed across Europe with astonishing speed, challenging the authority of the Catholic Church in ways previously unimaginable. Scientific advancements were shared and debated among a wider scholarly community, leading to a more rapid pace of innovation.

Consider the humble pamphlet. Before the press, a persuasive argument or a revolutionary idea might only reach a few hundred people. With it, thousands, even tens of thousands, could be reached. This democratized information and empowered individuals. Universities flourished, literacy rates began to climb, and a more informed populace started to question established norms. The vernacular languages gained prominence as more texts were printed in common tongues, rather than solely in Latin, further broadening access to knowledge.

Of course, the transition wasn’t instantaneous, nor was it without its complexities. The initial cost of setting up a printing press was significant, and it took time for printing houses to proliferate. Yet, the trajectory was clear. By the end of the 15th century, printing presses were operating in hundreds of European cities, churning out millions of books. The world had entered a new era, one where the power of the printed word could shape minds, ignite revolutions, and build civilizations.

The invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg was not merely a technological advancement; it was a cultural and intellectual watershed. It broke down the barriers of access to knowledge, empowering individuals and transforming the very fabric of society. The echoes of his ingenuity still reverberate today, in every book we read, every article we share, and every piece of information we access. It was, in essence, the dawn of the information age, a revolution sparked by metal, ink, and a visionary’s persistent spirit.