In the digital age, where information flows with unprecedented speed and volume, governments worldwide grapple with a familiar foe: the regulation of online content. Recently, Britain issued its first-ever online safety fine to the controversial US website 4chan. This modern skirmish over speech, obscenity, and responsibility echoes a long and often contentious history, a history that stretches back to a time when the “internet” was a mere whisper in the scientific community.

To understand the enduring challenges of online content regulation, we must travel back to the United States of 1873. It was in this year that a sweeping piece of legislation, the Comstock Act, was signed into law. Named after its fervent proponent, Anthony Comstock, a postal inspector and self-appointed guardian of public morality, the act aimed to eradicate “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” material from the mail. While its stated goal was noble—protecting the public from perceived moral decay—its reach was far broader and its implications more chilling than its proponents likely envisioned.

Comstock, a man of unwavering conviction, believed that vice was a creeping contagion that threatened the very fabric of American society. His particular targets were contraceptives and any information related to reproductive health. In his zeal, he saw these materials not as tools for family planning or personal autonomy, but as instruments of sin and moral corruption. The Comstock Act made it illegal to send “any article or thing designed or intended for the prevention of conception, or for causing the miscarriage of any woman pregnant” through the U.S. mail. This included not only the objects themselves but also any “letter, writing, or circular, picture, or engraving, or any other, of an indecent, lewd, lascivious, or obscene character.”

The cultural landscape of late 19th-century America was one marked by significant social and technological change. The rise of industrialization, rapid urbanization, and waves of immigration brought new anxieties and desires for social control. Alongside this, advancements in printing and distribution technologies made it easier than ever to disseminate information, both welcome and, in the eyes of figures like Comstock, unwelcome. The post, a ubiquitous and essential service, became the battleground for this cultural war.

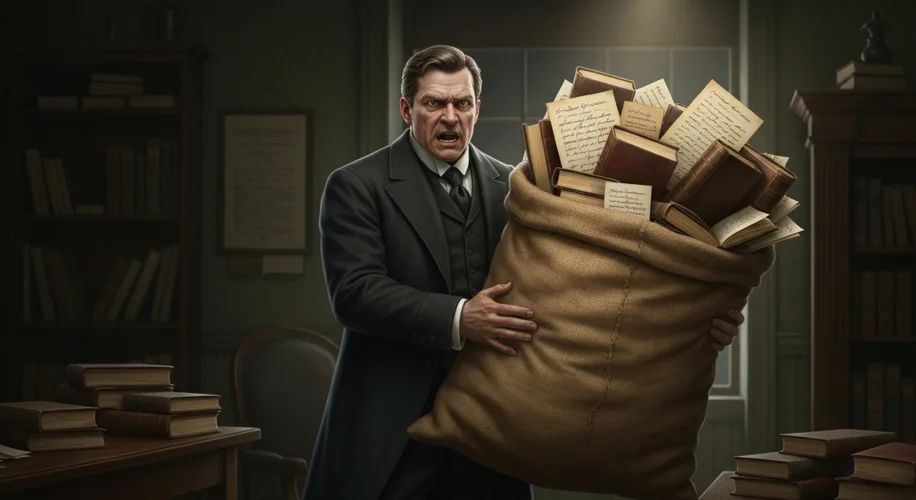

Comstock himself was a formidable force. Armed with his newfound authority as a special postal inspector, he actively pursued individuals he deemed immoral. He famously boasted of arresting hundreds of people, confiscating tons of “obscene” literature, and driving some of his targets to suicide. His methods were often aggressive, and his interpretation of “obscene” was notoriously broad, ensnaring not just pornography but also medical texts and even the dissemination of birth control information.

The consequences of the Comstock Act were profound and far-reaching. For decades, it served as a major obstacle to reproductive healthcare and education in the United States. Women seeking information about contraception or safe abortion were often denied access to it, leading to unsafe practices and significant health risks. The act fostered an environment of fear and silence around sexual health, a silence that would take generations to break.

Moreover, the Comstock Act laid a foundational precedent for governmental censorship and the control of information. It established a federal power to police morality through the mail, a power that would be invoked in various forms throughout the 20th century. The act’s broad language and its application by zealous enforcers highlight the inherent dangers of granting the state the authority to define and suppress speech it deems harmful.

Today, as we confront the challenges of regulating platforms like 4chan, the echoes of the Comstock Act are undeniable. The debates then mirrored those today: where is the line between protecting vulnerable individuals and stifling free expression? Who gets to decide what is “obscene” or “harmful”? What are the limits of governmental power in policing private communication?

While the technology has evolved from printing presses and mail carriers to the internet and social media algorithms, the fundamental tension remains. The Comstock Act, a relic of a pre-digital era, serves as a stark reminder that the struggle for free speech, privacy, and the responsible dissemination of information is not new. It is an ongoing conversation, a historical continuum that connects the moral crusades of the 19th century with the digital battles of the 21st. Britain’s fine on 4chan is not just a modern regulatory action; it is another chapter in a centuries-old story about who controls the narrative and what we are allowed to see and say.