In the hushed corridors of power, a familiar tension has resurfaced, echoing a conflict as old as journalism itself: the delicate dance between government transparency and national security. Today, we look back at a pivotal moment in this ongoing saga, a time when the press stood defiant against the might of the state, risking everything for the public’s right to know. We’re talking about the Pentagon Papers, a bombshell leak that, in 1971, sent shockwaves through Washington and irrevocably shaped the landscape of American press freedom.

The year is 1971. The United States is mired in the Vietnam War, a conflict that has deeply divided the nation and eroded public trust. For years, the government had been presenting a carefully curated narrative of the war – one of progress and eventual victory. But beneath the surface, a different story was unfolding, one of strategic missteps, escalating commitments, and a growing awareness within the administration itself that the war was, perhaps, unwinnable.

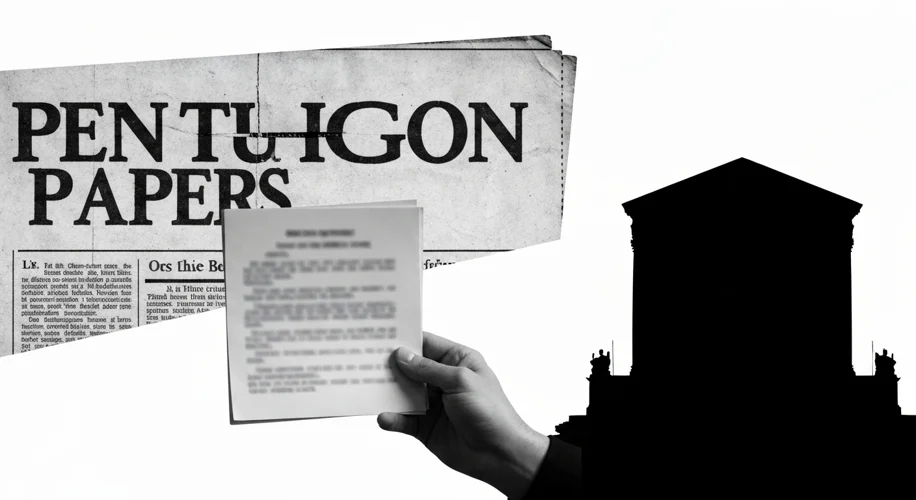

This hidden history was contained within a top-secret, 7,000-page document, commissioned by then-Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. Dubbed the Pentagon Papers, this massive study meticulously detailed the political and military decisions that had led the U.S. into the quagmire of Vietnam, from the Eisenhower administration through that of Lyndon B. Johnson. It was a chronicle of deception, not necessarily of malice, but of a pervasive belief that the public could not handle the unvarnished truth about the war’s grim realities.

Enter Daniel Ellsberg, a disillusioned former Pentagon analyst. Horrified by what he discovered within the classified study – the decades of misleading statements, the flawed strategies, the human cost of governmental hubris – Ellsberg felt a profound moral imperative to act. He began the arduous, clandestine process of copying the entire document, page by painstaking page, with the ultimate goal of bringing its contents to light.

His contact was Neil Sheehan, a journalist at The New York Times. Sheehan, a seasoned war correspondent, recognized the monumental significance of what Ellsberg was entrusting him with. After months of verification and legal review, on June 13, 1971, The New York Times began publishing excerpts from the Pentagon Papers. The revelations were staggering. The documents exposed how successive administrations had misled Congress and the public about the scope and prospects of the war, revealing a stark contrast between the public pronouncements and the private assessments of top officials.

The government’s reaction was swift and severe. President Richard Nixon and his administration, viewing the publication as an act of treason and a grave threat to national security, ordered the newspapers to cease publication. When The New York Times refused, the Department of Justice sought and obtained a federal court injunction, temporarily halting the series. But the story didn’t end there.

Other major newspapers, including The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, also received copies of the papers. Many of them, fueled by a belief in the public’s right to information and the imperative of a free press, decided to publish their own series. This created a legal standoff. The Nixon administration argued that the publication jeopardized national security, citing potential harm to diplomatic relations and military operations.

The case, New York Times Co. v. United States, quickly ascended to the Supreme Court. The nation watched with bated breath as the highest court grappled with a fundamental question: Could the government, through prior restraint, prevent the press from publishing information deemed classified, even if that information revealed governmental misconduct? On June 30, 1971, in a landmark 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the newspapers. The Court affirmed the principle of prior restraint being unconstitutional, stating that the government had not met the