The echoes of conflict have long resonated through the American experience, often less with the clash of armies and more with the strident arguments over deeply held beliefs, values, and who truly belongs in the nation’s narrative. These aren’t always shouts and protests; sometimes, they are quiet, determined movements chipping away at established norms, demanding a place at the table, and fundamentally altering the nation’s social and political landscape. The history of women’s rights in America is a prime example of such a profound, enduring ‘culture war.’

From the nation’s very inception, the promise of liberty and equality was largely a male construct. Women, even those of independent means, were relegated to the domestic sphere, their legal and social standing severely circumscribed. The prevailing culture dictated that a woman’s place was in the home, nurturing children and supporting her husband. Public life, politics, and intellectual pursuits were considered beyond their capacity and, frankly, their purview.

Yet, beneath this veneer of societal expectation, a powerful undercurrent of discontent began to stir in the 19th century. The Second Great Awakening, a fervent religious revival, paradoxically also fueled social reform movements. Women, often the most devout participants in these revivals, found themselves organizing and advocating for change. They became deeply involved in abolitionism, temperance, and education reform, which, in turn, exposed them to the stark inequalities they faced themselves.

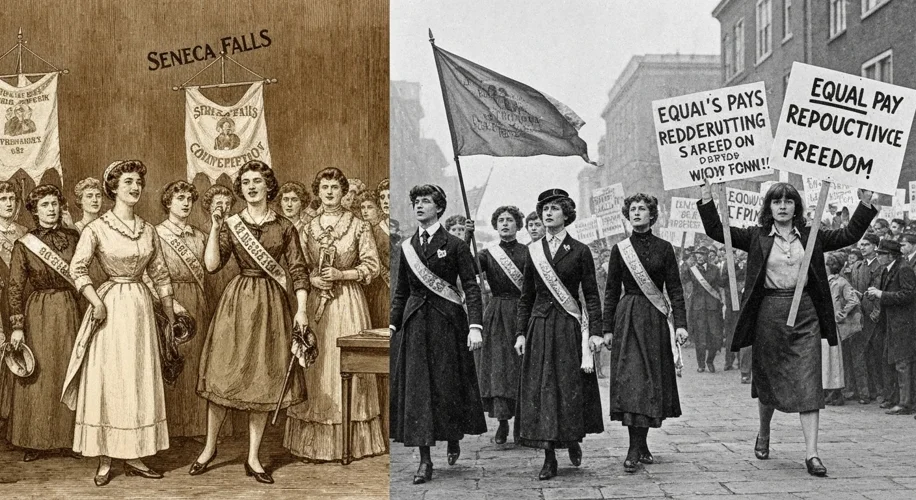

One of the most pivotal moments in this burgeoning movement was the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. Organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, this gathering of approximately 300 individuals, a mix of men and women, boldly declared that “all men and women are created equal.” They issued a “Declaration of Sentiments,” directly mirroring the Declaration of Independence, but crucially, it listed “a long train of abuses and usurpations” inflicted upon women, demanding rights including suffrage, property ownership, and equal access to education and employment.

This declaration was nothing short of revolutionary, igniting fierce opposition. Critics decried the very idea of women participating in public life as unnatural and destructive to the social order. Ministers preached against it, newspapers ridiculed the attendees, and many who signed the document faced social ostracism. The path to suffrage, the right to vote, became the central, yet fiercely contested, goal for decades. It was a battle fought in legislative halls, in public squares, and through tireless petitioning. Figures like Susan B. Anthony, a tireless organizer and speaker, became synonymous with the struggle, facing arrest for daring to vote in an election.

The fight for suffrage was not a monolithic entity. Different factions within the movement often clashed over strategies and priorities. Some prioritized a federal amendment, while others focused on state-by-state victories. The movement also intersected with other ‘culture war’ issues of the era, particularly race. The passage of the 15th Amendment, granting voting rights to Black men but not to women, created a painful rift, with some suffragists feeling betrayed.

The early 20th century saw the movement gain renewed momentum. Progressive Era reforms created a more fertile ground for social change. New tactics emerged, including more militant demonstrations, picketing the White House, and enduring hunger strikes in prison, which brought public attention and sympathy. Alice Paul and her National Woman’s Party were instrumental in these more confrontational approaches, even drawing parallels between the struggle for women’s rights and the fight for independence.

The culmination of this decades-long struggle arrived in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment, finally granting women the right to vote nationwide. However, this was not an end to the ‘culture war’ over women’s roles and rights. The mid-20th century brought about new waves of feminist activism, addressing issues beyond suffrage, such as equal pay, reproductive rights, and an end to discrimination in employment and education. The publication of Betty Friedan’s “The Feminine Mystique” in 1963 is often cited as a catalyst for this second wave of feminism, articulating the “problem that has no name” – the widespread dissatisfaction among suburban housewives.

These later movements also faced intense backlash. The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), proposed to guarantee equal legal rights for all American citizens regardless of sex, became a major battleground. Opponents, like Phyllis Schlafly, argued that the ERA would undermine traditional family structures and negatively impact women. The intense debate and lobbying efforts ultimately prevented the ERA from being ratified by the required number of states.

The history of women’s rights in America is a testament to the power of persistent advocacy against entrenched cultural norms and political opposition. It highlights how movements for social justice are often intertwined with broader ‘culture wars,’ challenging not just laws but fundamental beliefs about identity, equality, and the very fabric of society. The struggle for women’s equality, though achieving significant milestones, continues to be a dynamic force, shaping contemporary debates and demonstrating that the fight for full inclusion is an ongoing narrative in the American story.