The legions. The very word conjures images of disciplined, steel-clad warriors marching in perfect formation, their eagles glinting in the Mediterranean sun. They were the backbone of Rome, the instruments of its vast conquests. But peel back the gilded veneer of the Roman military machine, and you’ll find a truth often overlooked: the empire was not built by Romans alone. It was forged, expanded, and sustained by a diverse, often overlooked, array of peoples – the auxiliaries, the socii, and the foederati.

Imagine the early days of Rome, a fledgling city-state grappling for dominance in the Italian peninsula. To expand, Rome needed soldiers, and lots of them. Yet, Roman citizenship was a privilege not easily bestowed. This is where the socii – allies from Latin and other Italian communities – came into play. Bound by treaties, they provided Rome with vital manpower, fighting alongside Roman citizens. They were the first wave of Rome’s military might, their loyalty and fighting prowess crucial in subduing rivals and expanding Roman influence across Italy.

As Rome’s ambitions stretched beyond Italy, so too did its need for specialized troops. The legions, primarily heavy infantry, were not equipped for every battlefield. They needed skirmishers who could harass the enemy, archers to rain down death from afar, and cavalry to outmaneuver and pursue. These roles were increasingly filled by auxiliaries, recruited from the provinces and allied kingdoms across the ever-expanding empire. A Batavian auxiliary, renowned for his skill in riverine warfare, might patrol the Rhine frontier. A Cretan archer, with his deadly accuracy, could turn the tide of a battle. Numidian cavalry, swift and elusive, could outflank any enemy.

These men, often from cultures with long martial traditions, brought unique skills and weaponry to the Roman army. While legionaries drilled endlessly in the gladius and scutum, auxiliaries mastered their own traditional fighting styles. Think of the slingers from the Balearic Islands, whose projectiles could shatter shields, or the Syrian archers, whose volleys could decimate enemy formations before the legions even closed. They were the Swiss Army knives of the Roman military, filling critical gaps and allowing the legions to focus on their shock tactics.

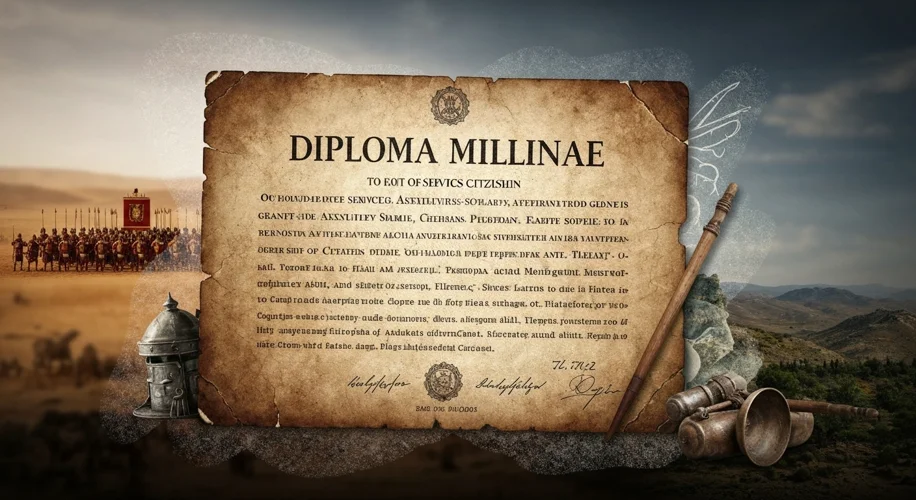

But integration wasn’t merely about battlefield utility. For auxiliary soldiers, service in the Roman army was a pathway to Roman citizenship, a prize of immense social and economic value. After serving for 25 years, an auxiliary soldier, and often his family, would be granted Roman citizenship. This was a powerful incentive, fostering loyalty and a sense of belonging that transcended ethnic and cultural differences. It was a pragmatic, if sometimes slow, process of Romanization, weaving these diverse peoples into the fabric of Roman society.

Consider the career of Tiberius Claudius Maximus, a Thracian auxiliary who served with distinction under Emperor Trajan. His military diploma, a physical testament to his service and subsequent citizenship, details his service in the Dacian Wars. This wasn’t just a military career; it was a transformation, granting him rights and status he could never have dreamed of in his homeland. His story, replicated thousands of times over, illustrates the profound impact of auxiliary service on individual lives and the broader Romanization of the empire.

By the late Republic and into the Empire, auxiliaries often outnumbered the legions. They were stationed in their own units, commanded by Roman officers, and integrated into the vast network of Roman fortifications and military bases. They were not merely hired help; they were an indispensable component of Rome’s military structure.

As the empire matured and faced new challenges, another category of troops emerged: the foederati. These were groups of barbarians who were permitted to settle within Roman territory, often on the frontiers, in exchange for military service. They were not fully integrated citizens but rather allied contingents, fighting under their own leaders, bound by treaties (foedera) to defend the empire. While this offered a seemingly endless supply of manpower, it also introduced a complex dynamic. The loyalty of foederati could be fickle, and their presence often led to friction with the local Roman populace and even the regular army.

The story of the Roman army is, therefore, incomplete without acknowledging the vital contributions of these non-Roman soldiers. They were the scouts who navigated treacherous terrain, the archers who softened enemy lines, the cavalry that pursued fleeing foes, and the garrisons that held the vast frontiers. Their service was not just a military necessity; it was a crucible in which disparate peoples were molded into a cohesive, albeit complex, imperial force.

Their integration, symbolized by the granting of citizenship, was a masterstroke of Roman policy. It transformed potential enemies into loyal defenders and stakeholders in the empire’s success. While the legions may have been the sharp edge of the Roman sword, it was the auxiliary forces, the socii and foederati, who provided the breadth, depth, and enduring strength that allowed Rome to conquer and, for centuries, to rule.

The legacy of these auxiliary troops is profound. They were the human bridges between Rome and the vast, diverse world it encompassed, demonstrating that the might of Rome was not solely a Roman achievement, but a testament to the collective might of those who fought for it, and in doing so, became part of its enduring story.