The air in Bronze Age Crete, thick with the scent of wild thyme and olive blossoms, also carried a sweeter, more precious aroma – that of honey. Long before the grandeur of the Minoan palaces at Knossos and Phaistos, and indeed, before the formidable citadels of the Mycenaeans rose on the mainland, the humble bee was a cornerstone of Aegean life. These tiny, industrious creatures provided not just a divine-tasting sweetener but also a vital source of light, medicine, and craft materials, weaving themselves into the very fabric of these advanced Bronze Age civilizations.

Imagine a world lit not by flickering oil lamps, but by the steady, clean burn of beeswax candles. Imagine a healer’s kit filled with potent salves, their efficacy amplified by the antimicrobial properties of honey. This was the reality for the Minoans and Mycenaeans, two sophisticated cultures that flourished between roughly 2700 and 1100 BCE.

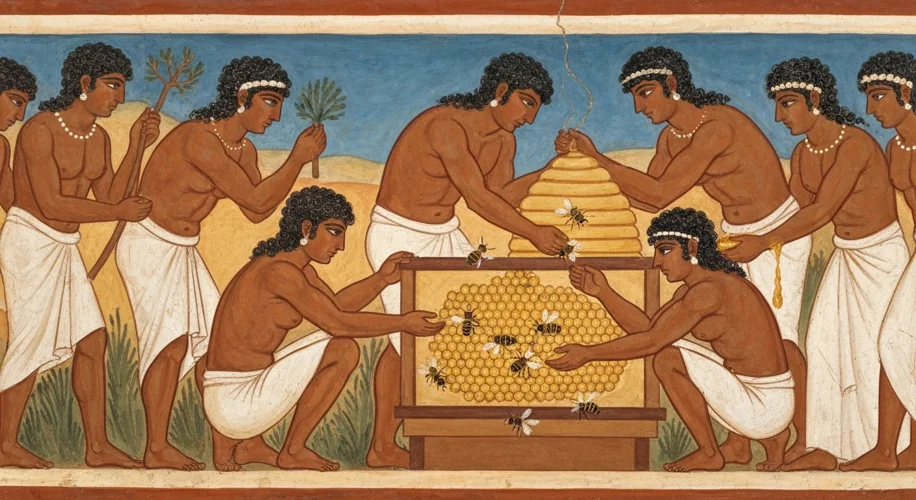

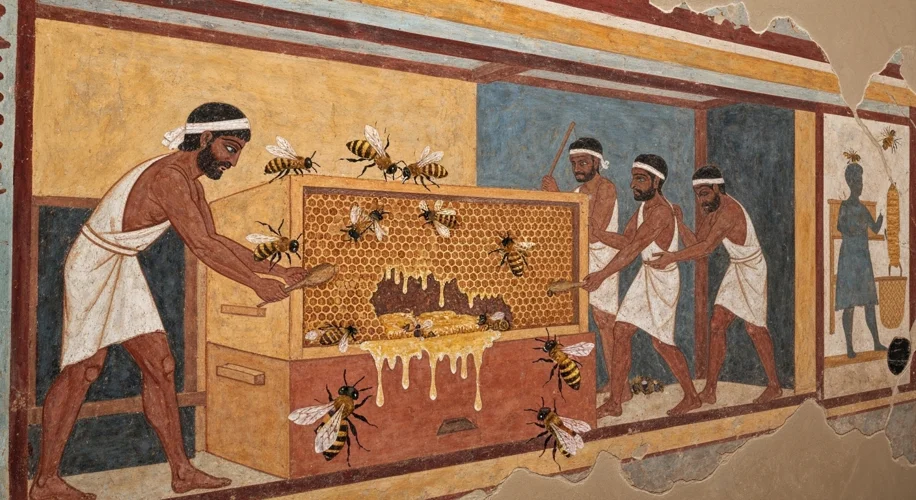

The earliest tangible evidence of beekeeping in the Aegean comes to us from Minoan Crete, a civilization renowned for its vibrant art, complex administration, and maritime prowess. Archaeological finds, particularly in the palaces and villas, reveal a deep appreciation for bees and their products. Elaborate pottery depicting bees and honeycombs, along with ancient hives carved from clay or wicker, speak to a sophisticated understanding of apiculture. The famous “Minoan Bee” fresco from Knossos, though its exact context is debated, likely depicts figures associated with beekeeping or honey collection, showcasing the bee as a symbol of fertility, prosperity, and even divinity.

Bees, revered by the Minoans, were seen as sacred creatures, messengers of the gods. Their honey, a rare and precious commodity in a world without refined sugar, was more than just a sweetener. It was a staple in their diet, a significant trade good, and a key ingredient in religious rituals and medicinal preparations. Ancient texts, though scarce, hint at honey’s medicinal uses, likely for its antibacterial and wound-healing properties. Imagine a Minoan physician carefully applying a honey-based poultice to a patient’s injury, the golden elixir working its slow, steady magic.

Beeswax, the other invaluable gift from the apiary, served equally crucial roles. It was molded into candles, providing the primary source of light for homes, workshops, and religious ceremonies after sundown. Without wax candles, the intricate administrative tasks, artistic endeavors, and social gatherings that characterized Minoan and Mycenaean life would have been severely curtailed. Wax also played a vital role in the creation of their exquisite artworks. It was used in the “lost-wax” casting technique, a method that allowed artisans to create detailed bronze figurines and tools. Imagine the painstaking process: a wax model meticulously crafted, then covered in clay, heated to melt the wax away, and finally, molten bronze poured into the hollow cavity.

The Mycenaeans, who rose to prominence on mainland Greece, inherited and adapted many aspects of Minoan culture, including their relationship with bees. While Minoan art often depicted bees more explicitly, Mycenaean artifacts, such as the gold pendant found at Mycenae featuring two bees flanking a honeycomb, clearly demonstrate the continued importance of these insects. The Linear B tablets, deciphered records from Mycenaean palaces, provide concrete evidence of honey’s economic significance. These administrative documents list quantities of honey allocated for various purposes, including religious offerings and perhaps even as payment for services. This suggests a well-organized system of honey collection and distribution, managed by the palace bureaucracy.

The importance of honey extended beyond the mundane. In Mycenaean society, honey was a ritualistic offering to the gods, symbolizing sweetness, purity, and abundance. It was likely consumed during feasts and ceremonies, reinforcing social bonds and expressing gratitude to the divine. The presence of honey in tombs further suggests its symbolic role in the afterlife, perhaps as a sustenance for the deceased on their journey to the underworld.

The transition from the Minoan to the Mycenaean era, and eventually to the so-called Greek Dark Ages, saw shifts in civilization but not a decline in the utility of bees. Even as palatial systems crumbled, the knowledge of beekeeping and the use of honey and wax persisted, laying the groundwork for their even more prominent role in Classical Greek society. Later Greek writers, such as Homer and Hesiod, would continue to sing the praises of honey, referring to it as “nectar” and a food fit for the gods.

In essence, the Aegean apiaries were more than just a source of a sweet treat. They were an integral part of the Bronze Age economy, religion, medicine, and technology. The careful tending of bees by Minoan and Mycenaean peoples provided the light that pushed back the darkness, the sustenance that nourished their bodies, and the materials that shaped their art and rituals. These buzzing, golden treasures, so seemingly insignificant, were in fact, pillars of civilization, their hum echoing through the millennia, a testament to the profound impact of nature’s smallest architects on humanity’s grandest achievements.