In the bustling marketplaces and quiet scriptoria of antiquity, a seemingly humble substance played a pivotal role in the machinery of civilization: beeswax. From the sun-baked plains of Mesopotamia to the marble halls of Rome, this golden treasure, harvested from the industrious labors of bees, was an indispensable commodity, shaping everything from written communication to religious devotion.

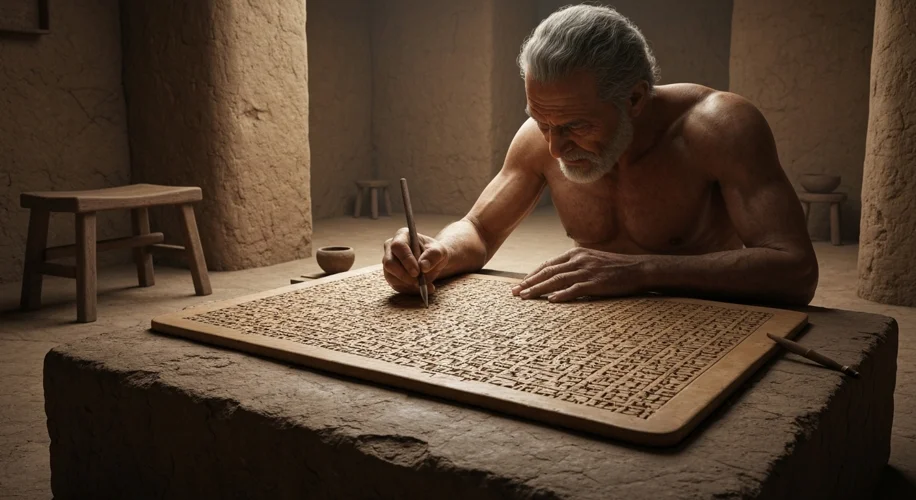

Imagine a scribe in ancient Sumer, thousands of years before the Common Era. His tools are simple: a stylus and a wooden board coated with a thin layer of dark, pliable wax. With a few swift strokes, he etches cuneiform script, recording harvests, laws, or perhaps a lover’s plea. This was the origin of the wax tablet, a precursor to paper and parchment, a fundamental tool that allowed the earliest civilizations to record their thoughts, their commerce, and their history. The very act of writing, of preserving knowledge, was often enabled by the silent work of bees.

But how did this precious wax reach these ancient hands? The story is one of early human ingenuity and the development of sophisticated trade networks. While wild honey and its comb were certainly utilized, the domestication of bees, or at least the systematic harvesting of their hives, began in earnest in these early societies. In Egypt, beekeeping was an established practice by the Old Kingdom (circa 2686–2181 BCE). Hieroglyphs and tomb paintings depict apiaries, showcasing the importance of bees not just for wax, but for honey, a vital sweetener and medicinal agent. Beekeepers would carefully remove sections of honeycomb, then melt the wax over gentle heat, separating it from the honey. This raw wax would then be purified, often through repeated melting and straining, to achieve the desired quality.

The reach of beeswax was far greater than the immediate vicinity of the hives. It became a valuable trade good, traversing vast distances along routes that predated the famous Silk Road. Coastal cities, river valleys, and mountain passes all became arteries of commerce. Traders would transport surplus wax from regions with abundant bee populations to areas where it was scarce but highly sought after. In Greece, for instance, beeswax was crucial for a variety of purposes. Artists used it to cast bronze statues through the ‘lost-wax’ method, a technique that allowed for intricate and detailed sculptures. It was also vital for sealing documents, an act of trust and authentication in a world without modern security measures. Imagine a Greek statesman carefully melting a dollop of beeswax onto a rolled papyrus, impressing his personal seal into the soft material – a guarantee of authenticity, a symbol of authority.

Rome, the empire that would come to define so much of the ancient Western world, inherited and expanded upon these uses. Roman scribes, like their Mesopotamian predecessors, relied on wax tablets for everyday writing, from school lessons to business transactions. The sheer scale of the Roman Empire meant that vast quantities of wax were required. This demand fueled an extensive trade network, with beeswax flowing in from across the Mediterranean, from North Africa, the Levant, and even further afield. Roman legions on campaign would carry wax tablets for their dispatches, and Roman administrators used wax seals to legitimize edicts that governed millions.

Beyond the practicalities of writing and crafting, beeswax held a significant place in the spiritual and personal lives of ancient peoples. In religious rituals, it was used to create votive offerings, to anoint sacred objects, and to fashion candles whose flickering flames illuminated temples and guided prayers. The purity and luminescence of beeswax made it a symbol of light and divine presence. In cosmetic practices, it was a key ingredient in salves, creams, and even early forms of makeup, helping to protect the skin from harsh elements and enhance beauty. The smooth, protective qualities of beeswax were highly valued.

The impact of beeswax on the ancient world cannot be overstated. It was a silent enabler of communication, a vital component of artistic and industrial processes, and an integral part of religious and personal life. The humble bee, through its production of wax, facilitated the spread of knowledge, the creation of enduring art, and the functioning of complex societies. When we consider the grand achievements of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome, it is worth remembering the small, golden contributions of their buzzing workers, whose wax helped build the very foundations of our civilization.