In the sweltering summer of 1518, the city of Strasbourg, then a bustling free imperial city within the Holy Roman Empire, became the stage for one of history’s most bizarre and unsettling episodes: the Dancing Plague.

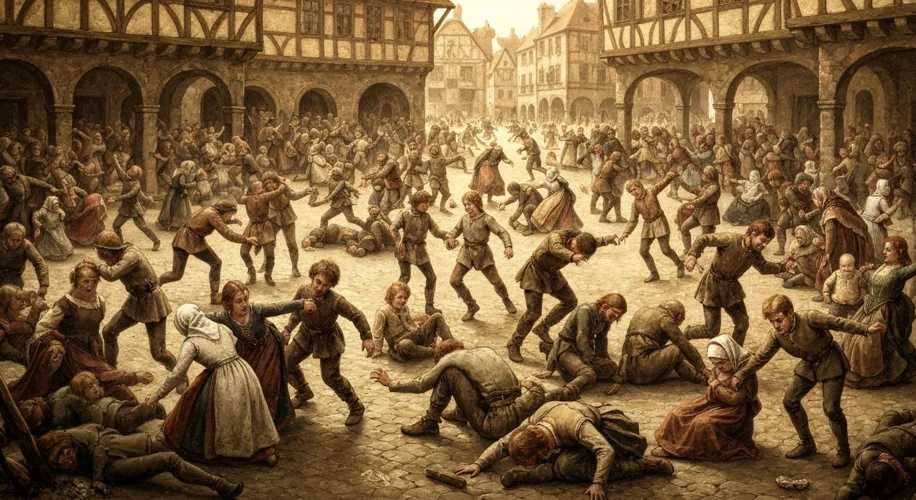

It began innocuously enough. Frau Troffea, a woman of middling social standing, stepped out into the streets one sweltering July day and began to dance. Not with joy, not with merriment, but with a frenzied, uncontrollable desperation. Her movements were wild, her face contorted in what appeared to be agony, yet she could not stop. Within a week, dozens more had joined her, their bodies wracked by the same inexplicable compulsion.

The authorities, bewildered and increasingly alarmed, initially resorted to what they believed was a logical solution: more dancing. They reasoned that if the affliction was caused by hot blood, then the dancers needed to expend that excess energy. They cleared open spaces, even erected a temporary stage, and encouraged the afflicted to dance their fevers away. Bards were hired to play music, hoping the rhythm might aid the process. The sick were even told to dance until they collapsed from exhaustion.

But the situation only worsened. The number of dancers swelled, reaching into the hundreds. Witnesses described a horrifying spectacle: men and women, young and old, prancing, twirling, and leaping through the streets for days on end. Their feet bled, their bodies gave out, and some, tragically, succumbed to exhaustion, heart attacks, or strokes. The air was thick with the groans of the suffering and the incessant, desperate rhythm of their movements.

Panic rippled through Strasbourg. What was this curse? Was it divine punishment for some unknown sin? Was it the work of malicious spirits? Theories abounded. Some blamed a supernatural curse sent by Saint Vitus, a figure associated with a similar, though less severe, phenomenon in the 10th century. Others whispered of ergot poisoning, a hallucinogenic fungus that grows on rye and can cause muscle spasms and psychotic episodes. The authorities, desperate for answers, even organized public processions and prayed for divine intervention, believing God’s wrath had been invoked.

As the plague raged through the summer, it eventually began to subside. By September, the phenomenon had largely vanished, leaving behind a city traumatized and baffled. The exact cause of the Dancing Plague of 1518 remains one of history’s enduring mysteries. While ergot poisoning is a popular theory, many historians point to the harsh living conditions of the time. Strasbourg in 1518 was suffering from famine, disease, and extreme poverty. The relentless heat of that particular summer likely exacerbated these hardships. Some scholars suggest that the plague was a form of mass psychogenic illness, a collective psychological response to extreme stress and societal anxieties. In such a state, the mind can manifest physical symptoms, leading individuals to act out their shared fears and anxieties in extraordinary ways.

The Dancing Plague serves as a stark reminder of the fragility of the human mind and body when subjected to immense social and environmental pressures. It was a time when superstition and nascent scientific understanding collided, leaving authorities and citizens alike in a state of bewildered horror, dancing to the tune of an unknown, and terrifying, affliction.