The grandeur of America’s National Parks – Yellowstone’s geysers, Yosemite’s granite cliffs, the Grand Canyon’s majestic abyss – often evokes a sense of pristine wilderness, a place untouched by human hands. Yet, beneath this idyllic surface lies a somber truth, a historical undercurrent of displacement and dispossession that continues to haunt these iconic landscapes. Long before the advent of the National Park Service, these lands were the ancestral homes of Indigenous peoples, vibrant cultures woven into the very fabric of the mountains, valleys, and rivers.

Imagine a people whose lives were intrinsically linked to the rhythm of the seasons, whose knowledge of the land was passed down through generations, a tapestry of oral histories, spiritual beliefs, and sustainable practices. For the Crow, Shoshone, Bannock, Paiute, and Miwok tribes, these lands were not mere scenery; they were sacred, providing sustenance, shelter, and spiritual connection. Their presence predated any European arrival by millennia, their footprints etched into the earth long before any park ranger’s boots would tread them.

The mid-to-late 19th century marked a brutal turning point. The burgeoning United States, driven by Manifest Destiny and a desire to “civilize” the West, began to view these ancestral lands not as occupied territories but as empty spaces ripe for preservation – and exploitation. The creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872 serves as a stark, early example. While hailed as a triumph of conservation, it was, for many Indigenous communities, a declaration of banishment.

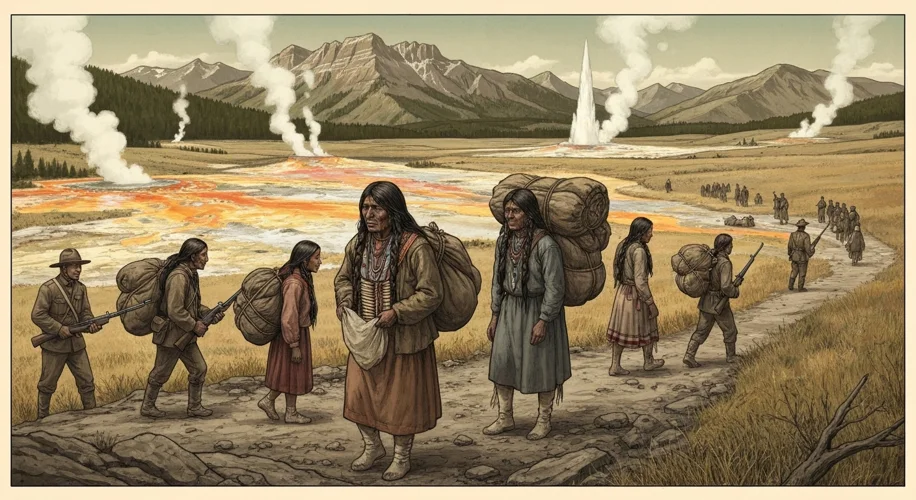

Consider the story of the Shoshone people. For generations, they had utilized the Yellowstone region for hunting and gathering, their movements dictated by the migration of game and the availability of resources. The park’s establishment, however, meant their traditional lifeways were deemed illegal. Hunting within the newly designated boundaries became a crime, and their access to vital food sources was severed. The U.S. Army, tasked with enforcing park regulations, actively removed Indigenous peoples, often through violent means. Families were separated, sacred sites were desecrated, and traditional practices were suppressed. The Bannock and Shoshone were forcibly driven from the area, their connection to their ancestral lands brutally severed.

Similar narratives unfolded across the country. In Yosemite, the Mariposa Indian War of 1851 saw the displacement of the Miwok people, paving the way for settlers and, eventually, the park’s designation. The Yosemite Grant Act of 1864, while granting Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove to California for preservation, explicitly aimed to remove Native Americans from the land. These policies were not merely oversight; they were deliberate actions rooted in a profound misunderstanding and, often, a willful disregard for Indigenous sovereignty and rights.

The underlying philosophy was one of exclusion. The dominant narrative of the era cast Indigenous peoples as obstacles to progress and preservation. The idea of coexisting with nature, of integrating human communities into a sustainable landscape, was largely absent. Instead, the ideal was a pristine, unblemished wilderness, an idea that conveniently ignored the fact that these lands had been managed and inhabited for millennia.

The consequences of these forced removals were devastating and long-lasting. Indigenous communities lost not only their homes and access to resources but also their cultural and spiritual anchors. The disruption of traditional lifeways led to economic hardship, social fragmentation, and the erosion of cultural identity. The psychological trauma of displacement and the loss of ancestral lands continue to resonate through generations.

Moreover, the establishment of these parks often benefited industries like tourism and resource extraction, which were facilitated by the absence of Indigenous presence. The very notion of