The year is 1839. Imagine a world where a vast, ancient empire, the Qing Dynasty of China, stands at a precipice, its once-unshakeable foundations beginning to crumble under the weight of internal pressures and external demands. Across the globe, a young, ambitious empire, Great Britain, fueled by the fires of the Industrial Revolution, is expanding its reach, its insatiable appetite for trade pushing its naval might to the far corners of the earth.

For decades, a delicate dance had been occurring between these two titans. The Chinese, proud of their rich civilization and self-sufficiency, operated under a restrictive trade system. Foreign merchants were confined to the bustling port of Guangzhou (Canton), and their interactions with the Qing court were strictly controlled. The British, however, saw this system as an impediment to their burgeoning economic interests. Their primary commodity of desire? Tea. But to pay for the vast quantities of Chinese tea that were rapidly becoming a staple in British households, they needed something the Chinese desperately craved in return.

That something was opium. Cultivated in British India, this potent narcotic was secretly, and then not-so-secretly, smuggled into China. The trade flourished, with British merchants amassing fortunes, while China found itself grappling with a burgeoning addiction crisis that was draining its silver reserves and corrupting its officials. The social and economic fabric of the nation was fraying.

Enter Lin Zexu, a resolute Qing official appointed Imperial Commissioner. He was a man of unwavering integrity and a deep concern for his nation’s welfare. Arriving in Guangzhou in 1839, Lin was appalled by the pervasive opium trade and its devastating consequences. He issued a stern ultimatum to the foreign traders: surrender all opium stocks or face severe consequences. The British Superintendent of Trade, Charles Elliot, caught between his nation’s economic interests and the looming threat of conflict, ultimately complied, but not without a hefty dose of defiance.

In a dramatic, almost theatrical act, over 20,000 chests of opium, worth millions of pounds, were publicly destroyed. This wasn’t just the destruction of a commodity; it was a defiant stand by China against what it perceived as exploitation. But for Britain, it was the final straw. The destruction of British property, coupled with ongoing trade disputes and the perceived insult to their national honor, provided the casus belli they had been seeking.

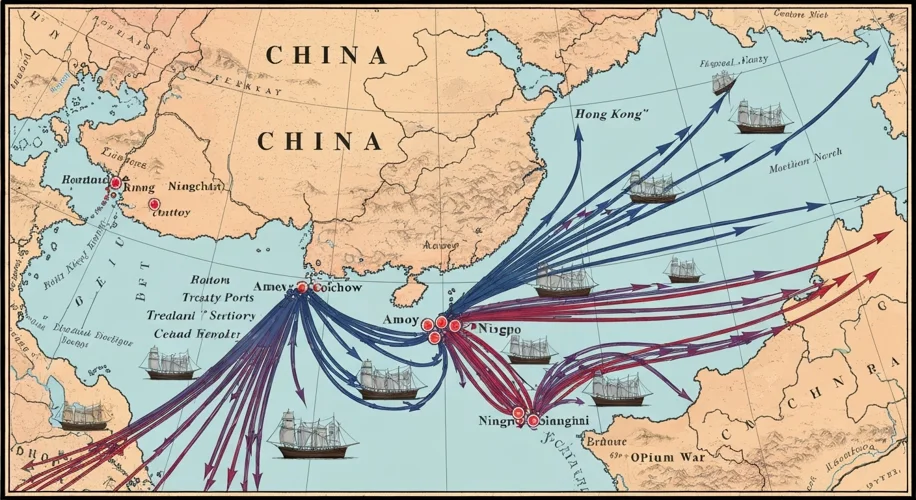

In 1840, the First Opium War erupted. The technologically superior British navy, with its steam-powered warships and advanced weaponry, was a force to be reckoned with. Chinese forces, though brave, were largely outmatched. The war was a swift and brutal affair. British ships sailed up the coast, bombarding coastal cities and forcing concessions.

The conflict culminated in the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, a document that would forever alter the course of Chinese history. The terms were humiliating for the Qing Dynasty. China was forced to cede the island of Hong Kong to Britain ‘in perpetuity.’ Five ‘treaty ports’ – Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai – were opened to foreign trade and residence, effectively creating enclaves where foreign laws often superseded Chinese ones. The treaty also imposed an ‘indemnity’ – a massive payment from China to Britain for the cost of the war and the destroyed opium.

But the consequences of the Opium War extended far beyond these immediate concessions. It shattered China’s long-held perception of itself as the ‘Middle Kingdom,’ the center of the civilized world. The war exposed the Qing Dynasty’s military and administrative weaknesses, fueling internal rebellions and further destabilizing the empire. It ushered in what many Chinese historians refer to as the ‘Century of Humiliation,’ a period marked by foreign interference, unequal treaties, and a loss of sovereignty.

For Britain, the war was a resounding success, consolidating its economic and geopolitical power in Asia. It paved the way for further imperial expansion and established a pattern of unequal relations with China that would persist for over a century. The opium trade, though officially discouraged after the war, continued to flow, perpetuating the social ills it had caused.

The First Opium War was not merely a conflict over trade goods; it was a collision of vastly different worldviews, economies, and imperial ambitions. It was a stark reminder of how power imbalances can shape history, leaving behind a legacy of resentment and a profound impact on the global geopolitical landscape that continues to resonate even today. It was the moment when the doors of China were forcefully opened, forever changing the destiny of both East and West.