In the tapestry of American history, few threads are as consistently woven with intrigue, drama, and undeniable impact as the story of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. More than just a law enforcement agency, the FBI has evolved from a nascent detective unit into a formidable force, grappling with the nation’s most heinous crimes and its most perilous security threats. Its narrative is one of transformation, marked by legendary directors, groundbreaking investigations, and a constant adaptation to the ever-changing landscape of law and order.

The seeds of the FBI were sown in the early 20th century, a time of burgeoning industrialization and increasing organized crime. Before its official inception, the Department of Justice relied on ad-hoc investigative methods. However, the need for a centralized, professionalized federal detective force became glaringly apparent. In 1908, Attorney General Charles J. Bonaparte, acting on the request of President Theodore Roosevelt, established the Bureau of Investigation (BOI), a small team of agents tasked with federal crimes. Its early years were modest, focusing on offenses like mail fraud and interstate theft.

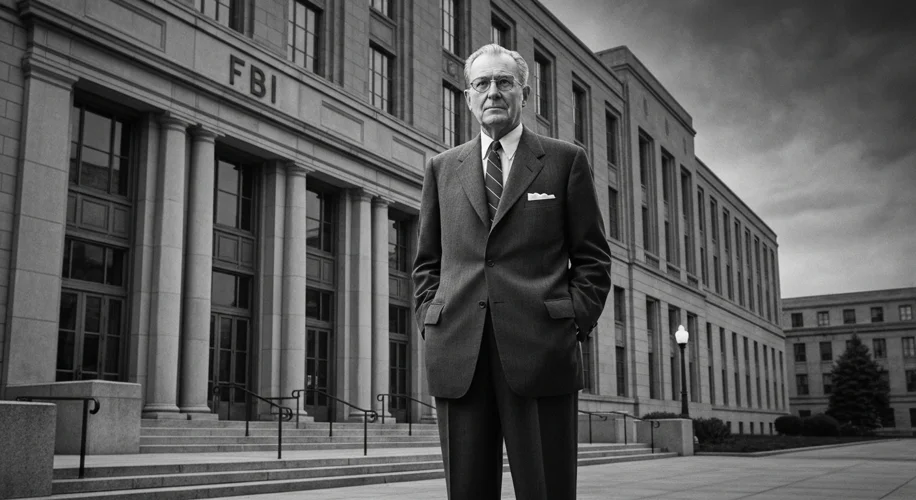

The true architect of the BOI’s transformation, and arguably the most influential figure in its history, was J. Edgar Hoover. Appointed director in 1924, Hoover was a man of immense ambition and iron will. He envisioned a bureau that was not only efficient but also incorruptible and technologically advanced for its time. Under his nearly five-decade tenure, the BOI was reorganized and renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1935. Hoover ruthlessly purged the bureau of any perceived weakness, established stringent training standards, and championed the use of scientific methods, including fingerprint analysis and ballistics.

Hoover’s FBI became synonymous with iconic crime-fighting. The 1930s saw the bureau relentlessly pursue notorious gangsters like John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, and Machine Gun Kelly. These high-profile cases, often sensationalized by the media, cemented the FBI’s image as the nation’s ultimate crime-fighting machine. The “Most Wanted” poster, a Hoover innovation, became a potent tool, striking fear into the hearts of fugitives and captivating the public imagination.

However, the FBI’s influence extended far beyond common criminals. As the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War escalated, the bureau’s mandate broadened dramatically to include national security and counter-espionage. Hoover, with his deep-seated suspicion of communism, turned the FBI into a powerful bulwark against perceived internal threats. The era saw extensive surveillance of political dissidents, civil rights activists, and anyone deemed a security risk, often through controversial and legally questionable means. Hoover’s unchecked power and his extensive, often personal, files on influential figures created a legacy that would be scrutinized for decades.

The post-Hoover era presented new challenges and demanded further evolution. Directors like J. Edgar Hoover’s successors, such as William Sessions and Louis Freeh, navigated the complex terrain of emerging threats like domestic terrorism, international organized crime, and cybercrime. The Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 and the September 11th attacks in 2001 profoundly reshaped the FBI’s priorities, leading to a significant expansion of its counter-terrorism capabilities and a closer integration with intelligence agencies.

Today, the FBI stands at the nexus of traditional law enforcement and modern intelligence gathering. Its agents are equipped with sophisticated technology, from advanced forensic tools to vast digital surveillance capabilities. They investigate everything from white-collar fraud and cyberattacks to international espionage and domestic extremism. The bureau’s commitment to its motto, “Fidelity, Bravery, Integrity,” continues to guide its operations, even as it grapples with the ethical and legal complexities of 21st-century investigations.

The history of the FBI is a compelling narrative of adaptation and power. It reflects the evolving anxieties and priorities of the United States, from the roaring twenties and the gangster era, through the McCarthyist purges and the Cold War, to the digital age of cyber threats and global terrorism. Its directors, its agents, and its investigations have left an indelible mark on American society, shaping our understanding of justice, security, and the constant, often unseen, battle against those who seek to undermine the republic.