Imagine a nation where the very shape of its democracy could be molded, twisted, and reformed, not by the will of the people, but by the stroke of a pen drawing lines on a map. This is the potent reality of redistricting in the United States, a practice that has seen the Supreme Court step into the political arena time and again, attempting to balance fairness with the inherent partisanship of drawing electoral districts.

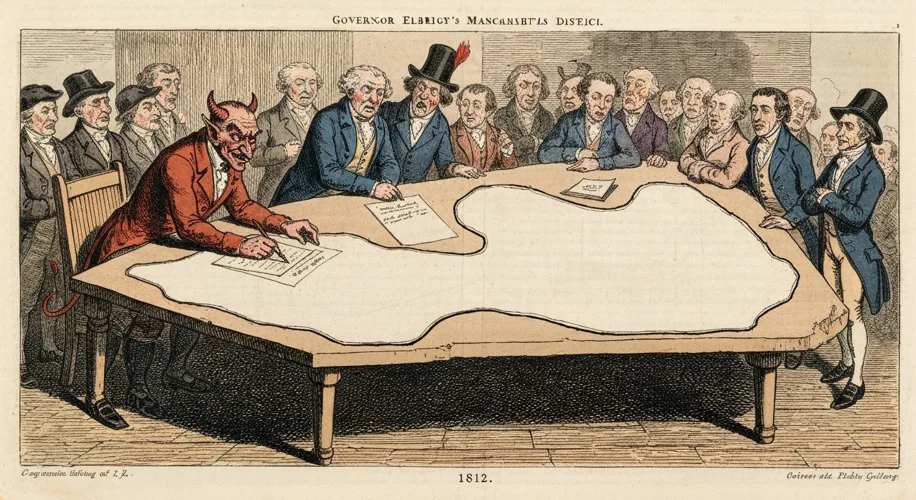

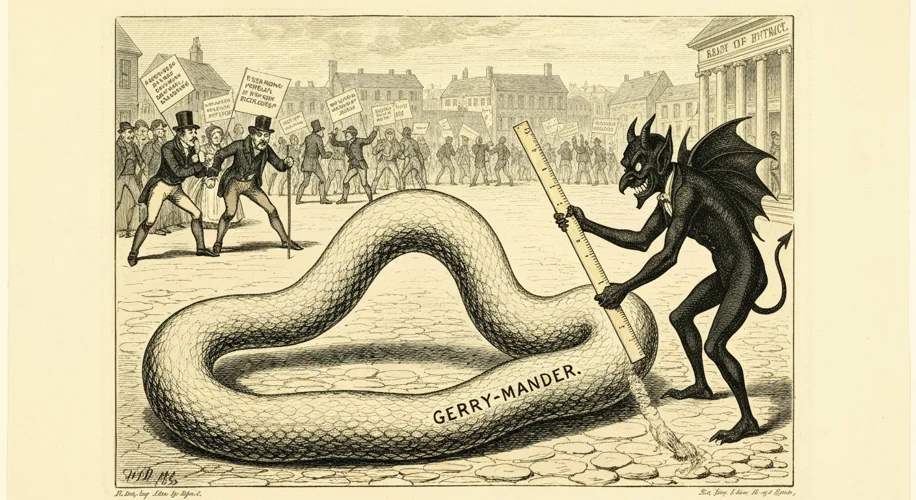

From the earliest days of the Republic, the drawing of congressional districts was a matter left to the states. The Constitution, in Article I, Section 4, grants states the power to prescribe “the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives,” but it also gives Congress the power to “at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations.” This delicate balance, however, did not foresee the sophisticated, often ruthless, manipulation that would come to be known as gerrymandering – a term born from the peculiar shape of a district drawn in Massachusetts in 1812 to favor Governor Elbridge Gerry. His name, contorted with “salamander,” gave us the enduring, and often ugly, word: gerrymander.

The Supreme Court’s initial stance was one of reluctance to intervene in what was seen as a purely political question. For decades, the Court largely deferred to state legislatures, even when districts were drawn with blatant disregard for fairness or representation. The prevailing view was that if voters disliked the way their districts were drawn, they should vote the party responsible out of office. This hands-off approach, however, allowed for the entrenchment of power, where incumbents could effectively choose their voters, rather than the other way around.

This dynamic began to shift in the latter half of the 20th century. Landmark cases started to chip away at the Court’s abstention. In Baker v. Carr (1962), the Court ruled that challenges to malapportioned legislative districts did present a justiciable question, meaning federal courts could hear such cases. This decision, while not directly about gerrymandering, opened the door for future challenges based on the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The true turning point came with Reynolds v. Sims (1964), which established the principle of “one person, one vote” for state legislative districts. This meant that districts within a state must be roughly equal in population. This was a monumental victory for fair representation, aiming to end the practice of rural overrepresentation and urban underrepresentation.

However, the line between malapportionment (unequal population) and gerrymandering (manipulative drawing for political advantage) remained blurry. For years, the Supreme Court grappled with how to address racial gerrymandering. In Shaw v. Reno (1993), the Court struck down a North Carolina congressional district drawn primarily to maximize African American representation, ruling that districts drawn based on race, even with benign intent, violated the Equal Protection Clause. This decision sparked a complex and ongoing debate about race, representation, and the intent behind redistricting.

The most significant modern challenges to gerrymandering have focused on partisan gerrymandering. For decades, the Court largely held that partisan gerrymandering claims were non-justiciable political questions. This meant that while the practice was undeniably unfair and often blatant, the courts would not intervene. This doctrine, known as the “political question doctrine,” effectively shielded partisan gerrymandering from judicial review.

However, the floodgates were opened, or at least nudged, with cases like Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004), which, though it didn’t establish a clear standard, hinted at the possibility of a justiciable claim if a manageable, neutral standard for evaluating partisan gerrymandering could be found. The debate continued, with numerous cases attempting to define what constituted an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander. Critics pointed to deeply skewed election results where a party could win a majority of seats while losing the popular vote – a clear sign of manipulation.

In Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Supreme Court delivered a major blow to challenges against partisan gerrymandering. The Court held that partisan gerrymandering claims are not justiciable in federal courts, effectively declaring that such claims present political questions that must be resolved by Congress or the states themselves. The majority argued that there was no judicially manageable standard to identify and remedy partisan gerrymandering, and that federal courts should not enter such a volatile political arena.

This decision was met with widespread criticism. Opponents argued that it left voters defenseless against extreme partisan gerrymandering, allowing politicians to continue to draw districts that entrench their power, discourage voter participation, and exacerbate political polarization. Proponents, however, argued that it was a necessary step to keep the judiciary out of inherently political matters and that redistricting should be left to the political process and state legislatures.

The legacy of the Supreme Court’s involvement in redistricting is a complex tapestry. While landmark decisions like Baker and Reynolds established crucial principles of fair representation, the Court’s struggles with the nuances of partisan gerrymandering, culminating in the Rucho decision, have left many questioning the future of fair elections. The lines on the map continue to shift, and the battle for truly representative districts remains a central, and often contentious, feature of American democracy. The Supreme Court’s journey through these cases reflects not just legal interpretations, but also the enduring tension between political power and the democratic ideal of equal voice.

The implications are profound. Gerrymandering can lead to less competitive elections, making it harder for new voices to emerge and harder for voters to hold their representatives accountable. It can contribute to political extremism, as representatives in safe districts may cater to their party’s base rather than seeking broader consensus. The ongoing debate highlights a fundamental question: when does the drawing of lines become so manipulative that it undermines the very foundation of representative government?