The year is 1918. The world, already reeling from the Great War, is about to face an enemy far more insidious and invisible: the Spanish Flu. This microscopic killer would sweep across continents, leaving in its wake a trail of devastation so profound that it claimed more lives than all the battles of World War I combined. In the face of such overwhelming odds, humanity’s greatest defense, often unseen and unsung, has been the vaccine.

The story of vaccines is not just a tale of scientific triumph; it’s a narrative woven through centuries of public health crises, societal skepticism, and hard-won battles for acceptance. It’s a story that begins long before the advent of the microscope, in a world where fear and superstition often held sway over reason.

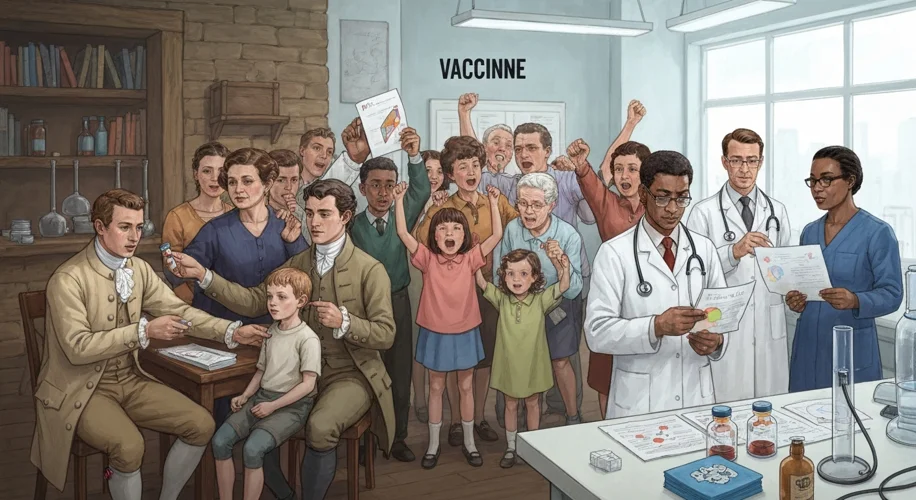

Our journey starts in the late 18th century, with a keen-eyed English country doctor named Edward Jenner. The specter of smallpox loomed large, a disease that left survivors disfigured and often blind, and killed millions. Jenner observed that milkmaids, who contracted a milder disease called cowpox, seemed to be immune to smallpox. This sparked a daring hypothesis. In 1796, he conducted a now-legendary experiment: he took material from the pustules of a milkmaid and inoculated an eight-year-old boy, James Phipps. When he later exposed Phipps to smallpox, the boy remained healthy. The era of vaccination had begun.

Jenner’s discovery was revolutionary, yet its adoption was far from immediate. Resistance, fueled by fear of the unknown and religious objections, was rampant. Some viewed the procedure as unnatural, even heretical. Yet, the undeniable efficacy of vaccination in combating smallpox gradually chipped away at the skepticism. By the mid-19th century, smallpox vaccination had become a cornerstone of public health in many parts of the world.

The 20th century, however, would bring new challenges and accelerate vaccine development at an unprecedented pace. The early 1900s saw the rise of infectious diseases like polio, diphtheria, and measles, which continued to cast a long shadow over childhood. The development of vaccines against these diseases was a painstaking process, often fraught with setbacks.

One of the most significant advancements came with the development of the polio vaccine. Polio, a virus that could paralyze and kill, struck terror into the hearts of parents worldwide. Dr. Jonas Salk’s inactivated polio vaccine, announced in 1955, was a monumental achievement. The public reaction was one of overwhelming relief and celebration. In the United States, children lined up by the millions to receive the life-saving injection, a stark contrast to the fear that had gripped the nation.

However, the path was not always smooth. The Salk vaccine faced initial hurdles, including a tragic incident in 1955 involving a batch of vaccine that caused polio in some recipients. This led to the development of Dr. Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine, which became widely used in the following decades and played a crucial role in the near-eradication of the disease globally.

These developments highlighted the critical role of advisory panels and scientific review boards. In the wake of public health crises, these bodies became essential for evaluating the safety and efficacy of new vaccines, providing guidance to public health officials, and building public trust. They represented a more structured, evidence-based approach to vaccine deployment, moving beyond the more ad-hoc methods of earlier centuries.

But the 20th century also witnessed intense public health debates and controversies surrounding vaccination campaigns. The introduction of new vaccines often coincided with periods of heightened public anxiety and misinformation. The 1970s and 80s, for instance, saw the rise of concerns about the pertussis (whooping cough) vaccine, with some linking it to neurological disorders. While extensive scientific research has largely debunked these links, these controversies underscore the persistent challenge of communicating scientific information effectively to a diverse public.

The advent of the internet and social media in the late 20th and early 21st centuries has amplified these challenges. Misinformation can spread at an alarming rate, often overshadowing rigorous scientific evidence. Debates surrounding vaccine mandates, the timing of childhood immunizations, and the safety of new vaccines have become increasingly polarized.

Yet, the historical record is undeniable. Vaccines have been one of humanity’s most powerful tools in combating infectious diseases. From the eradication of smallpox to the dramatic reduction in cases of polio, measles, and diphtheria, vaccines have saved countless lives and prevented untold suffering. They have allowed children to grow up without the specter of disfigurement and death, and enabled societies to flourish free from the constant threat of devastating epidemics.

As we look back on the history of vaccine development, we see a recurring pattern: a relentless scientific pursuit met with a spectrum of public reaction, from eager acceptance to deep-seated suspicion. The ongoing public health challenges, particularly in the wake of recent global health events, underscore the enduring importance of robust vaccine programs, transparent communication, and a continued commitment to scientific rigor. The shield of humanity, forged through centuries of innovation and perseverance, continues to be our most potent defense against the unseen enemies that threaten our well-being.