The hum of an assembly line, the gleam of polished chrome, the roar of an engine – these are the visceral sounds and sights of the automotive industry. For decades, this global powerhouse has dictated economic tides, shaping cities and influencing nations. But beneath the polished hood, the engine of this industry has been in constant motion, with factories relocating and trade policies flexing like steel beams under pressure. This isn’t just about where cars are made; it’s a story of global ambition, economic pressure, and the complex dance between corporations and countries.

Imagine the post-World War II era. America was the undisputed king of the road. Its sprawling factories, fueled by wartime innovation and a booming domestic market, churned out vehicles that became symbols of freedom and prosperity. Brands like Ford, General Motors, and Chrysler were not just car manufacturers; they were American icons, employing millions and anchoring entire communities. Yet, even then, the seeds of change were being sown. As other nations rebuilt and industrialized, the cost of labor and production began to shift.

The 1970s marked a turning point. Japan, having recovered remarkably from the war, emerged as a formidable competitor. Its car manufacturers, notably Toyota and Honda, introduced smaller, fuel-efficient, and remarkably reliable vehicles. This wasn’t just a product innovation; it was a strategic conquest. Japanese companies began to establish a foothold in the lucrative American market, and soon, the question arose: why build these cars in expensive American factories when they could be produced more economically elsewhere?

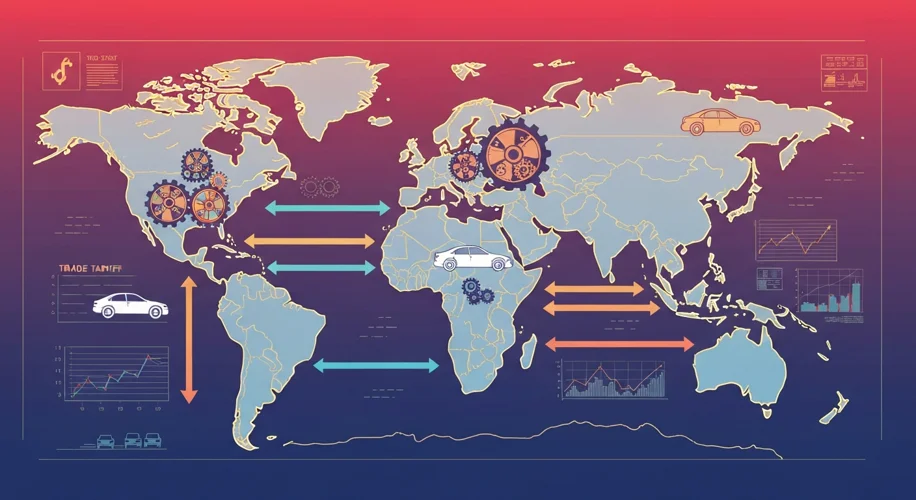

This is where the concept of “globalization” truly began to rev its engine in the automotive world. Companies started to look beyond their home borders. Initially, it was about accessing cheaper labor and raw materials. Mexico, with its proximity to the U.S. and lower wages, became an attractive destination. Then came the broader sweep across the Pacific to Asia, and eventually, to Eastern Europe as old political barriers crumbled.

This geographical shift wasn’t always smooth. As factories closed in traditional manufacturing hubs like Detroit, entire towns faced economic devastation. The iconic “Rust Belt” became a poignant symbol of this industrial exodus, leaving behind empty factories and communities struggling to reinvent themselves. The human cost was immense: skilled workers found themselves unemployed, their livelihoods vanishing with the relocated assembly lines.

Simultaneously, these cross-border movements ignited trade disputes. Governments, keen to protect their domestic industries and jobs, began to implement protectionist policies. Tariffs, quotas, and local content requirements became weapons in this economic warfare. The United States, for example, has frequently engaged in trade disputes with countries like Japan, Germany, and more recently, China, over alleged unfair trade practices and currency manipulation, all with the automotive sector often at the epicenter.

Think of the “Chicken Tax” in the United States, a 25% tariff imposed on light trucks and vans that has been in place since 1964. Originally intended to retaliate against European tariffs on American chicken, it has had a profound impact on the automotive industry, effectively preventing most foreign automakers from importing light trucks into the U.S. and encouraging them to build factories within the country instead.

Another significant period of tension arose in the early 2000s when the U.S. imposed tariffs on imported steel and aluminum, impacting car manufacturers who relied on these materials. The retaliatory measures and the subsequent uncertainty created a volatile environment for global automotive supply chains.

The perspectives in these disputes are varied and often conflicting. Corporations argue for free trade and the efficiency of globalized production, citing lower costs and greater consumer choice. Governments, however, often champion the need to protect domestic jobs, national security interests (given the strategic importance of the auto industry), and to ensure a level playing field. Labor unions, naturally, focus on safeguarding the livelihoods of their members, advocating for policies that keep manufacturing jobs at home.

The consequences of these relocations and trade wars are far-reaching. On one hand, globalization has led to more affordable vehicles for consumers worldwide and has fostered economic growth in developing nations. It has spurred innovation as companies compete on a global scale. On the other hand, it has contributed to job displacement in developed countries, increased economic inequality, and created complex geopolitical tensions that can spill over into other areas of international relations.

Today, as we stand in 2025, the automotive industry is undergoing another seismic shift with the rise of electric vehicles and autonomous driving. This technological revolution is poised to trigger new waves of manufacturing relocations and potentially reignite old trade disputes, as countries vie to lead in battery production, software development, and the assembly of these next-generation vehicles. The lessons learned from past industrial migrations and trade wars will undoubtedly shape how this new era unfolds, reminding us that the road ahead for the automotive industry, much like the industry itself, is constantly under construction.

Ultimately, the story of automotive industry relocations and trade disputes is a microcosm of globalization itself. It’s a narrative of economic imperatives clashing with national interests, of technological advancement driving industrial change, and of the enduring human desire for prosperity and security. The cars we drive are more than just machines; they are the products of a complex, often contentious, global economic narrative.