The air in Tehran in 1979 crackled with more than just the dry desert heat; it thrummed with a revolutionary fervor that would soon shake the world. For decades, Iran had been under the increasingly autocratic rule of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a monarch who, backed by Western powers, had pushed for rapid modernization. But this modernization came at a cost, alienating swathes of the population and creating deep fissures within Iranian society.

A Land Divided

Beneath the glittering surface of Westernized urban centers, a deeply conservative religious establishment felt increasingly marginalized. The Shah’s reforms, which included secularizing education, expanding women’s rights, and redistributing land from religious endowments, were seen by many as an assault on Islamic values and traditions. The Shah’s relentless pursuit of Westernization, coupled with his authoritarian tactics and the infamous SAVAK secret police, fostered widespread resentment. Whispers of discontent turned into murmurs, and murmurs into a growing chorus of opposition.

The Ayatollah’s Return

At the heart of this burgeoning opposition was a charismatic and uncompromising cleric: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Exiled by the Shah in 1964, Khomeini had continued to rally his followers from afar, denouncing the Shah’s rule as corrupt, decadent, and subservient to foreign powers, particularly the United States, which he famously dubbed the “Great Satan.” His fiery sermons, smuggled back into Iran on cassette tapes, resonated deeply with a populace yearning for a return to what they saw as authentic Iranian and Islamic identity.

The year 1979 marked a seismic shift. Protests, initially sparked by student demonstrations, rapidly escalated into nationwide strikes and marches. The Shah’s government, once seemingly invincible, began to crumble under the immense pressure. Security forces, once loyal, started to waver, and in some instances, joined the protestors. The Shah, his authority dissolving like sand through fingers, eventually fled Iran in January 1979, seeking medical treatment abroad.

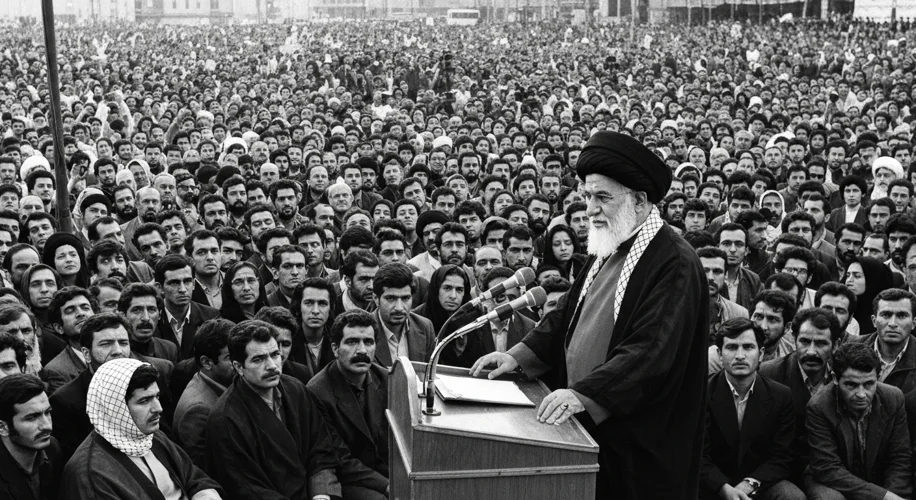

Khomeini’s triumphant return in February 1979 was met with scenes of jubilation. Millions poured into the streets to welcome him, believing he was their liberator. The old order was dismantled, and the Pahlavi dynasty, which had ruled Iran for over five decades, was brought to an abrupt end. What followed was a nationwide referendum, and in April 1979, Iran was declared an Islamic Republic, a revolutionary new system of governance.

A New Dawn, A New Order

The establishment of the Islamic Republic was not merely a political upheaval; it was a profound cultural and social transformation. The new constitution enshrined Ayatollah Khomeini as the Supreme Leader, granting him ultimate political and religious authority. Islamic law, Sharia, became the basis of the legal system, and many of the Shah’s reforms were reversed.

The revolution’s impact reverberated far beyond Iran’s borders. It challenged the Western-backed order in the Middle East and inspired Islamist movements across the region. The seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran later that year, and the subsequent hostage crisis, became a potent symbol of the revolution’s anti-Western stance and plunged Iran into international isolation.

A Legacy of Transformation

Today, in 2025, the Iranian Revolution remains a pivotal moment in modern history. It demonstrated the potent force of popular discontent fueled by religious and nationalist sentiment, and it fundamentally reshaped Iran’s identity and its place in the world. The revolution’s legacy is complex, marked by both the establishment of a unique theocratic state and ongoing debates about freedom, human rights, and Iran’s role on the global stage. It stands as a testament to how deeply held beliefs can ignite transformative change, forever altering the course of a nation.