Long before the age of radio waves and printing presses, even before the ink dried on the earliest scrolls, humanity had discovered a potent tool: propaganda. It wasn’t a sterile, academic concept; it was woven into the very fabric of their existence, shaping their understanding of the world and their place within it. Ancient civilizations like Egypt and Sumer, the cradles of human society, were not merely building cities and inventing writing; they were, in essence, crafting their own origin stories, not just for themselves, but for humanity itself. And in doing so, they laid the groundwork for a phenomenon that continues to shape our world today.

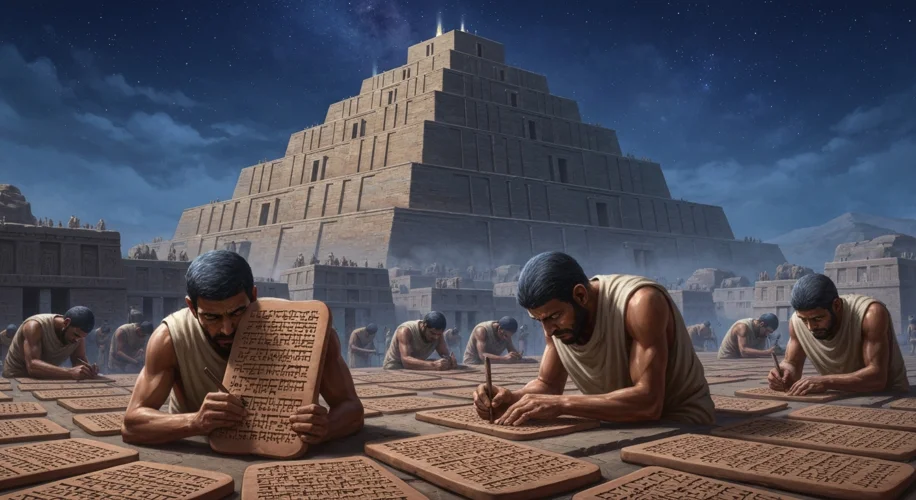

Imagine the sun-baked plains of Mesopotamia, where the Sumerians, around the 4th millennium BCE, were carving out a new existence. They were the world’s first city-builders, astronomers, and mathematicians. But how did they perceive their own beginnings? Their myths spoke of gods shaping humans from clay, imbuing them with breath and purpose. These weren’t just bedtime stories; they were foundational narratives that legitimized their social structures, their divine kingship, and their understanding of the cosmos. The epic tales of Gilgamesh, a king whose exploits blended the divine and the mortal, served not only as literature but as a powerful tool to reinforce the king’s connection to the gods and his mandate to rule.

Meanwhile, on the fertile banks of the Nile, the ancient Egyptians were constructing a civilization of unparalleled grandeur and longevity. Their consciousness of their own historical beginnings was deeply intertwined with their religious beliefs and their unique understanding of kingship. Pharaohs, seen as divine intermediaries, were not just rulers but gods on Earth. Their monumental constructions, from the towering pyramids to the colossal temples, were not merely feats of engineering; they were powerful visual statements designed to awe, inspire, and convey an unshakeable message of divine authority and eternal order. The very act of building these structures was an act of propaganda, solidifying the pharaoh’s power and the people’s belief in the cosmic significance of Egypt.

The Egyptians meticulously recorded their history, their triumphs, and their divine lineage on tomb walls and papyri. These inscriptions, filled with hieroglyphs depicting gods, kings, and scenes of daily life and the afterlife, served as a constant reinforcement of their worldview. They believed their civilization was divinely ordained, a perfect model of order (Ma’at) in a chaotic universe. While they didn’t possess a concept of “human history” as we understand it, they were acutely aware of their unique and ancient origins, believing their civilization to be the pinnacle of creation. They didn’t need to recognize their pioneering role in human history in a self-aware, academic sense; their entire cultural framework was built on the premise of being the original, the divinely appointed, the eternal.

Consider the Narmer Palette, dating back to around 3100 BCE. This ceremonial artifact, with its intricate carvings, depicts King Narmer uniting Upper and Lower Egypt. It’s not just a historical record; it’s a piece of political art, a visual declaration of unification and the king’s absolute power. This was propaganda in its purest form: a powerful, easily understood message designed to shape perception and legitimize rule. Every chisel mark was a word, every image a slogan.

These early civilizations, in their quest to understand their own existence and legitimize their societies, inadvertently became the architects of propaganda. They didn’t see themselves as manipulating public opinion; rather, they were expressing a divinely sanctioned truth. Their myths, their art, their monumental architecture – all served to reinforce a shared understanding of origins, purpose, and power. They were pioneers not just in agriculture or writing, but in the very human art of shaping narratives to build and maintain civilization. Their legacy is not just in the ruins they left behind, but in the enduring power of the stories they told, stories that continue to echo through the millennia.

What can we learn from these ancient masters of narrative? Perhaps it’s a reminder that the desire to shape perception is as old as civilization itself. From the grand ziggurats of Sumer to the towering pyramids of Egypt, these ancient peoples understood the power of visuals, of compelling narratives, and of reinforcing a collective identity. They didn’t have mass media, but they had the enduring power of shared stories and monumental statements, tools that, in their own way, were just as effective in shaping minds and forging empires.