The year is 1973. Santiago, Chile, a city once vibrant with political discourse, now hums with an undercurrent of unease. President Salvador Allende, a democratically elected socialist, stood at the helm of a nation grappling with deep social and economic divides. His “Chilenization” policies, aimed at nationalizing key industries like copper mines, had endeared him to the working class but stoked the fears of the elite and foreign investors.

The air crackled with tension. Protests, strikes, and counter-protests had become commonplace. The political landscape was polarized, a microcosm of the Cold War’s global ideological struggle. The United States, wary of a socialist experiment in its backyard, covertly supported opposition forces. Meanwhile, within Chile, the military, historically a guardian of the republic, found itself increasingly entangled in the political fray.

On September 11, 1973, that unease erupted into a brutal reality. Tanks rolled into Santiago, fighter jets screamed overhead, and the presidential palace, La Moneda, became the focal point of a violent assault. General Augusto Pinochet, the army commander-in-chief, led the military coup that toppled Allende’s government. The images that emerged were stark: La Moneda ablaze, symbols of a democratically elected government reduced to rubble.

Allende himself refused to surrender. In a final, defiant broadcast from the besieged palace, he declared his unwavering commitment to his people and his ideals. “I will not resign,” he stated, his voice firm against the din of battle. He would die that day, a martyr for his cause, his death officially ruled a suicide, though questions have lingered through the decades.

The coup marked the beginning of a dark chapter for Chile. Pinochet’s regime, which lasted for 17 years, ushered in an era of systematic repression. Political opponents were silenced, disappeared, tortured, and killed. Thousands were forced into exile. The once vibrant public sphere was choked by fear and censorship. The “Chicago Boys,” a group of Chilean economists trained in the United States, implemented radical free-market reforms, privatizing state industries and liberalizing trade, which, while stabilizing the economy in some respects, also deepened social inequality.

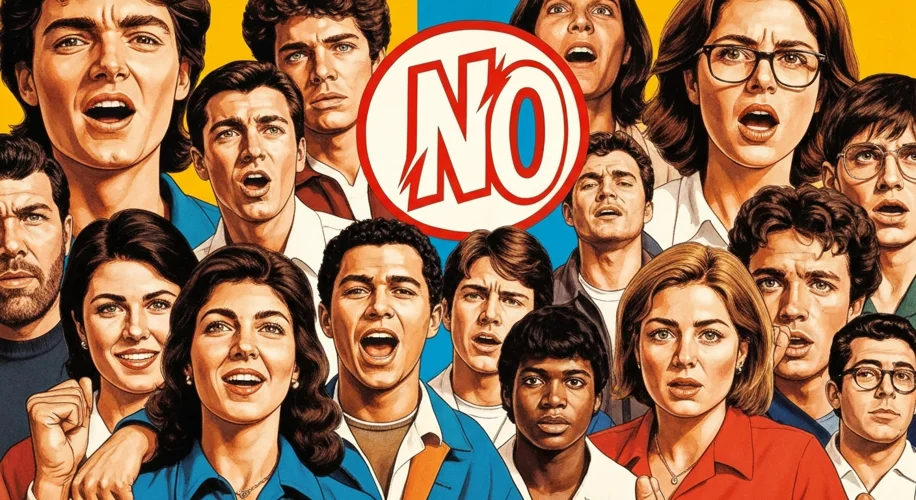

Yet, even under the iron fist of dictatorship, the seeds of resistance began to sprout. Small acts of defiance grew into organized movements. The “No” campaign, a courageous grassroots effort in the 1988 plebiscite, challenged Pinochet’s rule directly. Millions of Chileans, yearning for freedom, cast their votes against the dictator’s continued tenure. The outcome was a resounding defeat for Pinochet, a testament to the unyielding spirit of the Chilean people.

The transition to democracy was not instantaneous, nor was it without its challenges. The lingering shadow of the dictatorship, the economic disparities, and the quest for justice for the victims of human rights abuses continued to shape Chile’s political landscape. However, the resilience demonstrated in the “No” campaign marked a pivotal moment, a collective awakening that paved the way for a more open and democratic society.

The story of Chile’s military dictatorship and its subsequent transition to democracy is a powerful reminder of the fragility of democratic institutions and the enduring human desire for freedom and justice. It is a narrative woven with threads of betrayal, resilience, and ultimately, hope. It teaches us that even in the darkest of times, the voices of the people, united in their pursuit of a better future, can indeed dismantle the strongest of walls and usher in the dawn of a new day.