In the bustling, gas-lit streets of Victorian London, amidst the clatter of horse-drawn carriages and the scent of coal smoke, a revolutionary idea took root. It was the winter of 1843, and the modern world, teetering on the brink of immense change, was about to gain a new, cherished tradition: the Christmas card.

Before this innovation, the custom of sending holiday greetings was a far more personal and time-consuming affair. Letters, painstakingly penned by hand, were dispatched, often arriving long after the festive season had passed. This was a world without the instantaneity of modern communication, a time when distance felt vast and the pace of life, though different, was still measured.

Enter Sir Henry Cole, a visionary civil servant and a man of considerable ambition. Cole, who was instrumental in establishing the London postal system, found himself overwhelmed by the sheer volume of personal correspondence he was expected to send during the Christmas season. He was a busy man, with important work on public administration and the Great Exhibition of 1851 occupying his thoughts. Sending individual letters to all his acquaintances simply wasn’t feasible. He needed a more efficient solution, a way to convey festive cheer without sacrificing precious time.

Cole, a keen observer of social trends and a proponent of the arts, approached his friend John Callcott Horsley, a renowned painter of the era. Together, they hatched a plan: to create a single, mass-producible greeting that could be sent to many people at once. This was the genesis of the Christmas card.

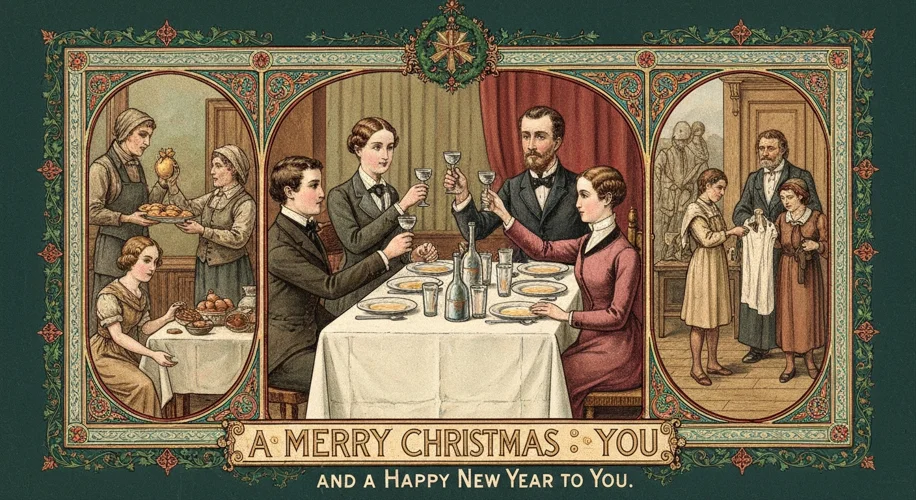

The result was a lithographed card, a masterpiece of Victorian design and sentiment. It depicted a sprawling, joyous scene: a family gathered around a table, raising their glasses in a toast to Christmas. Flanking this central image were two smaller panels, illustrating acts of charity—one showing the giving of food to the hungry, the other the clothing of the poor. Across the bottom, in elegant script, were the words, “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to You.”

This was no mere illustration; it was a carefully curated message. Cole, a man of progressive ideals, intentionally included the scenes of charity. In an era marked by stark social inequalities, he wished to remind recipients that the spirit of Christmas extended beyond personal celebration to encompass compassion and benevolence towards the less fortunate.

Horsley, perhaps drawing inspiration from religious art and contemporary genre paintings, imbued the scene with warmth and conviviality. The family, dressed in their finest Victorian attire, exuded happiness and familial love, creating an idealized vision of the holiday season. The card was, in essence, a miniature artwork, a portable piece of festive cheer.

This innovative concept was brought to life by the printer William Egley, who produced an initial run of 1,000 cards. These were not distributed as we might buy them today; they were sold for one shilling each, a considerable sum at the time, making them a luxury item. Despite the price, the cards were a success, selling out quickly and paving the way for future Christmas card production.

The impact of Cole’s brainchild was profound and far-reaching. The Christmas card quickly captured the public imagination. It offered a convenient and affordable (eventually) way to maintain social connections during the holiday period, especially for those living far apart. The trend spread rapidly throughout Britain and across the Atlantic to America, where artists and printers soon began creating their own designs.

By the 1870s and 1880s, Christmas cards had become a ubiquitous part of the holiday season. Lithography techniques improved, making cards more colorful and intricate. Designs evolved from religious imagery and winter scenes to include flowers, animals, and sentimental verses. The practice became a democratic one, accessible to nearly everyone, transforming the way people expressed their holiday wishes.

The Christmas card was more than just a piece of decorated paper; it was a symbol of connection, a tangible expression of goodwill in an increasingly industrialized world. It fostered a sense of community and shared celebration, transcending social strata and geographical boundaries.

Looking back from our vantage point in 2025, it’s easy to take the Christmas card for granted. Yet, its creation by Sir Henry Cole in 1843 was a moment of true ingenuity. It was an innovation born out of necessity and a desire to connect, a small but significant step that continues to brighten our holidays, proving that even the simplest of traditions can carry the weight of history and the warmth of human connection.