The year is 1950. The world is still reeling from the devastation of World War II, and a new kind of conflict is brewing – the Cold War. In this era of uncertainty, crime was evolving, becoming more organized and more elusive. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), under the leadership of J. Edgar Hoover, recognized a growing problem: a cadre of dangerous criminals who had mastered the art of disappearing. These were not petty thieves; these were murderers, kidnappers, and bank robbers whose freedom posed a constant threat to public safety.

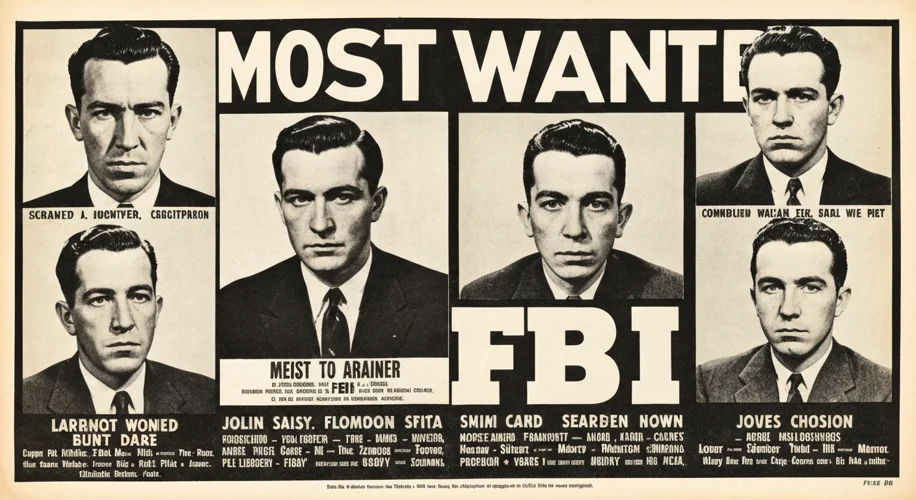

To combat this escalating challenge, on March 14, 1950, the FBI launched a program that would forever change the landscape of criminal pursuit: the Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. It was a bold move, a public declaration that no criminal was too cunning to escape justice. The initial list was a chilling catalog of the era’s most notorious offenders, individuals whose faces would soon become etched into the American psyche.

The Genesis of a List: From Public Urgency to Psychological Warfare

The idea for the list wasn’t born in a vacuum. It emerged from a direct request by the FBI to the Associated Press for information on the most significant escaped fugitives. The AP, in turn, canvassed its news bureaus across the country, compiling a list of over 60 individuals. The FBI then culled this list, selecting the ten most dangerous and those who had evaded capture for the longest periods. The goal was clear: leverage the power of the press to turn the public against these fugitives, making them the hunted in a nationwide game of cat and mouse.

This wasn’t just about providing wanted posters; it was about creating a psychological weapon. By making these criminals household names, the FBI aimed to create an environment where they could no longer blend in. The theory was that someone, somewhere, would recognize them, would remember a face from a newspaper or a radio broadcast, and would come forward. The list transformed ordinary citizens into potential informants, embedding the pursuit of justice into the fabric of daily life.

Evolution of a Brand: From Sepia Tones to Digital Footprints

The early years of the Ten Most Wanted list saw a steady stream of successes. Fugitives like Arthur “Doc” Barker, a member of the infamous Barker-Karpis gang, were apprehended thanks to public tips generated by their inclusion on the list. The iconic images of these wanted men, often stark black-and-white mugshots, became a fixture in post offices and newsstands across America. The psychological impact was undeniable. For the fugitives, it meant a constant, gnawing paranoia. Every glance, every hushed conversation, could be the one that led to their downfall.

As technology advanced, so too did the FBI’s methods. The list evolved from simple newspaper clippings to more sophisticated public appeals. In 1969, the FBI began distributing wanted posters with more detailed descriptions and, crucially, photographs. The advent of television brought the faces of these fugitives into living rooms nationwide, amplifying the list’s reach and impact. By the late 20th century, the internet had revolutionized information dissemination. The FBI’s website became a crucial tool, allowing for real-time updates and wider global access to the Most Wanted list.

The Psychology of the Hunt: Fear, Fame, and the Ultimate Price

The psychological toll on fugitives placed on the Ten Most Wanted list is immense. The constant need to look over one’s shoulder, to adopt new identities, and to live in perpetual fear of discovery creates an unsustainable existence. The notoriety, while a consequence of their crimes, also becomes a suffocating cloak. The very fame the list bestows is a double-edged sword, ensuring that they are never truly free.

Consider the case of Ted Kaczynski, the