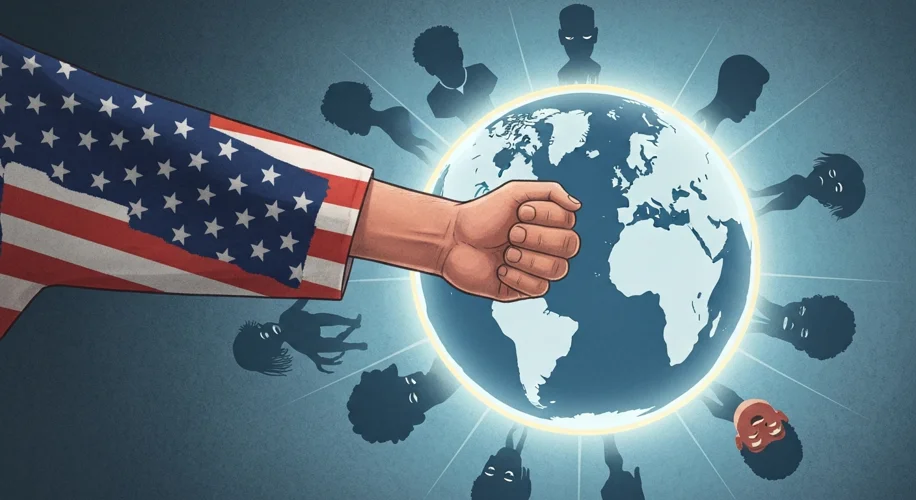

The United States, a nation forged in revolution and dedicated to self-determination, has long held a complex and often tumultuous relationship with international organizations. From the grand pronouncements of global peace to the swift pronouncements of withdrawal, this dance between engagement and isolation has echoed throughout American history, shaping its identity on the world stage.

Imagine, if you will, the year is 1919. The Great War, a cataclysm that had engulfed Europe and drawn in nations from across the globe, had finally sputtered to a halt. The air was thick with both exhaustion and a fervent hope for a lasting peace. At the forefront of this idealistic charge was Woodrow Wilson, the American President, a man who believed passionately in the power of collective security. He championed the League of Nations, an ambitious project designed to prevent future wars through diplomacy and mutual understanding.

But back home, a different sentiment was brewing. The war had exacted a heavy toll, and many Americans felt a profound weariness of foreign entanglements. The Senate, imbued with its constitutional power to ratify treaties, became the battleground. Led by figures like Henry Cabot Lodge, a powerful conservative voice, the opposition argued that the League would drag the United States into countless international disputes, compromising its sovereignty. The debate was fierce, pitting Wilson’s globalist vision against a resurgent wave of American isolationism. In the end, the Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, and the United States, the very nation that had proposed it, stood apart from the League of Nations, a powerful symbol of its internal struggle between international engagement and national self-interest.

This historical echo, the League of Nations saga, is not an isolated incident. It represents a recurring theme in America’s foreign policy. Throughout the 20th and into the 21st century, the United States has swung between embracing multilateralism and retreating into a more unilateralist stance.

The post-World War II era saw a significant shift. Haunted by the failures of the interwar period, the US became a principal architect of a new global order. The United Nations was founded in 1945, with the US playing a leading role. This period marked an era of unprecedented American leadership in international institutions, from the Bretton Woods system that established the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a military alliance designed to counter Soviet aggression.

Yet, even within this era of robust engagement, the seeds of doubt were sown. Debates often raged about the cost of participation, the perceived infringement on American sovereignty, and the effectiveness of these bodies. Different administrations have approached these questions with varying degrees of enthusiasm. Some have sought to strengthen these organizations, while others have viewed them with skepticism, at times even seeking to curb their influence or, in extreme cases, disengage entirely.

A striking modern parallel to the League of Nations debate emerged in recent years. Under the Trump administration, the United States announced its intention to withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO). The rationale cited was the organization’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, with accusations of bias towards China and general mismanagement. This move sent shockwaves across the globe, highlighting the fragility of international cooperation when a leading power falters in its commitment.

The withdrawal was ultimately reversed by the Biden administration, but the episode underscored the enduring tension. It revealed how deeply partisan these decisions could become, and how quickly decades of commitment could be called into question. The arguments echoed those of the League of Nations era: concerns about sovereignty, cost, and perceived ineffectiveness were once again at the forefront.

Why this perpetual back-and-forth? Several factors contribute to America’s complex relationship with international bodies.

- Ideology and Identity: The American narrative is deeply rooted in individualism and self-reliance. This can sometimes clash with the collectivist ethos required for robust international cooperation. The very idea of surrendering even a degree of autonomy to a global body can be a difficult pill to swallow for a nation that prides itself on its independence.

- Economic Considerations: Membership in international organizations often comes with financial obligations. Debates frequently arise about whether the economic benefits of participation outweigh the costs. Critics argue that American tax dollars could be better spent at home, while proponents emphasize the long-term economic stability and trade opportunities that global engagement provides.

- Perceived Ineffectiveness or Bias: When international organizations are perceived as failing to achieve their stated goals, or as being unfairly influenced by other nations, public and political support can wane. Accusations of inefficiency, bureaucracy, or political bias often fuel calls for withdrawal.

- Domestic Politics: The decision to join or leave an international organization is rarely made in a vacuum. Domestic political considerations, the shifting moods of the electorate, and the strategies of political parties often play a significant role. International engagement can become a potent symbol in partisan battles.

The consequences of these shifting tides are profound. When the US fully engages, it can lend immense weight and legitimacy to global efforts, from peacekeeping to pandemic response. Conversely, when it withdraws or expresses deep skepticism, it can weaken these institutions, undermine global cooperation, and create power vacuums that other nations may seek to fill, sometimes with less benign intentions.

Ultimately, America’s relationship with international organizations is not a simple story of consistent commitment or consistent rejection. It is a dynamic, evolving narrative, a reflection of the nation’s internal debates about its role in the world. The tension between the desire for global leadership and the deeply ingrained impulse for self-determination continues to shape its foreign policy, leaving a legacy of engagement, withdrawal, and constant re-evaluation on the world stage.

As we look to the future, the question remains: will America find a more stable equilibrium in its engagement with the global community, or will the pendulum continue to swing, leaving a trail of disrupted alliances and uncertain futures in its wake?