Imagine a world bathed not in the electric glow of screens, but in the flickering dance of candlelight and the scent of woodsmoke. This was medieval Europe, a time when art wasn’t a casual hobby, but a rigorous, lifelong calling. For the aspiring artist, the path was rarely straight, often fraught with hardship, yet illuminated by the potential for creating works that would echo through centuries.

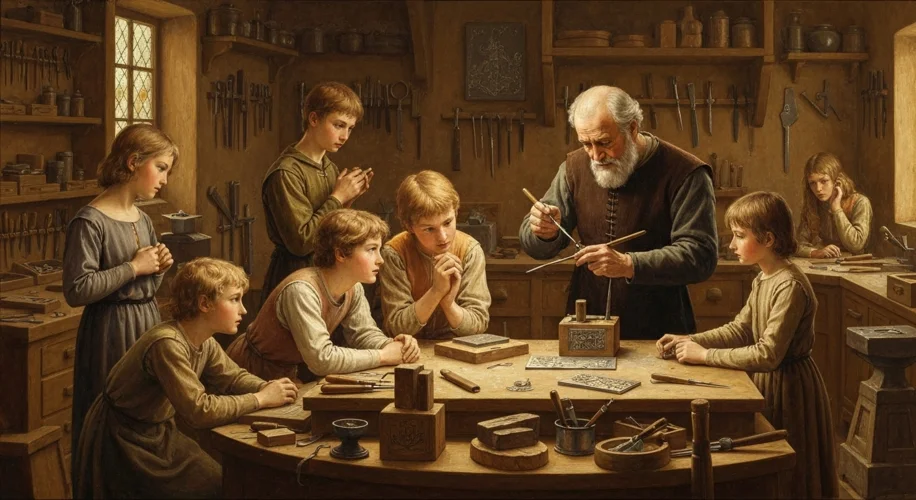

The journey typically began in childhood, not in a sterile studio, but within the bustling, often grimy, workshops of established masters. At the tender age of seven or eight, a boy might be apprenticed to a painter, a sculptor, a goldsmith, or an illuminator. This wasn’t a matter of choice in the modern sense; often, it was a familial arrangement, a way to secure a trade and a future. The apprenticeship was a brutal crucible. For years, sometimes a decade or more, the apprentice was little more than a glorified servant. His days were filled with menial tasks: grinding pigments, preparing vellum, sweeping floors, and running errands. He learned by observing, by imitating, and by endless repetition.

Consider the life of a hypothetical apprentice named Thomas, in 14th-century Florence. His master, a renowned fresco painter, demanded absolute obedience. Thomas awoke before dawn, tended the master’s fires, and then began his day’s labor. He might spend hours meticulously preparing a wall for a fresco, a task requiring the precise application of successive layers of plaster. Or perhaps he’d be tasked with grinding lapis lazuli, a precious blue pigment imported from distant Afghanistan, a process that turned his hands blue for days and filled the air with fine dust. Mistakes were met with harsh words, or worse, a stinging slap from the master’s rule.

Yet, within this strict hierarchy, the seeds of artistry were sown. Thomas would learn the foundational principles: the subtle mixing of colors, the anatomy of the human form, the principles of perspective (still a developing art), and the devotional narratives that fueled most artistic commissions. He would copy master drawings, learning to capture the drapery of a robe or the serene expression of a saint.

Once his apprenticeship was complete, Thomas might become a journeyman. This was a period of greater freedom, but often precariousness. He would travel from city to city, seeking work in various workshops. This itinerant life allowed him to absorb different styles and techniques, broadening his artistic vocabulary. He might assist on major cathedral projects, contribute to altarpieces, or even take on smaller commissions himself. The life of a journeyman was one of constant striving, of proving one’s skill to earn the next meal and the next commission.

The ultimate goal for many was to become a master craftsman. This required not only exceptional skill but also financial independence and guild membership. To achieve master status, an artist typically had to present a “masterpiece” – a work of exceptional quality that demonstrated his complete command of his craft. This could be a complex altarpiece, an intricately carved sculpture, or a beautifully illuminated manuscript.

Patronage was the lifeblood of medieval art. Churches, monasteries, wealthy merchants, and nobles commissioned artworks to adorn their sacred spaces, their homes, and to demonstrate their piety and status. A powerful patron could transform an artist’s fortunes, providing a steady income and the opportunity to undertake ambitious projects. However, this also meant artists were beholden to the tastes and demands of their patrons. A duke might insist on specific colors or imagery, overriding the artist’s own vision. The artist’s personal expression was often secondary to the patron’s narrative or devotional requirements.

Consider the renowned Limbourg brothers, who created the stunning “Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.” Their patron, John, Duke of Berry, was one of the most influential figures of his time. The brothers worked for him for years, creating some of the most exquisite illuminated manuscripts ever produced. Their access to precious materials and their freedom to develop their unique style were direct results of this powerful patronage.

Challenges abounded. The cost of materials, especially imported pigments like ultramarine blue derived from lapis lazuli, could be exorbitant, limiting the scale and richness of artworks. The guilds, while providing structure and quality control, could also be insular, making it difficult for outsiders or those with unconventional styles to gain entry.

Despite these hurdles, the medieval artist pursued a calling that was both a craft and a devotion. Their work was an integral part of society, serving spiritual, social, and political functions. From the soaring cathedrals filled with stained glass to the intimate devotional books, medieval art was a testament to human skill, faith, and the enduring pursuit of beauty in a world far removed from our own. The apprentice who endured years of grinding pigments and sweeping floors dreamed of the day his own hand would bring divine stories to life, adorning the world with enduring splendor.