Imagine a bustling Roman harbor, the air thick with the cries of merchants and the scent of salt and exotic spices. Ships, heavy with cargo, jostle for space. Among the most vital goods are the ubiquitous amphorae, their distinctive pointed bottoms piercing the sky as they are hoisted from the holds. These aren’t just clay pots; they are the unsung heroes of ancient commerce, their very shape a testament to ingenious, functional design honed over millennia.

From the sun-drenched shores of the Mediterranean to the far-flung outposts of the Roman Empire, the amphora was the go-to container for everything from wine and olive oil to garum (a fermented fish sauce that was a staple condiment) and honey. But why the sharp, pointed base? It’s a question that might seem trivial, but the answer lies at the heart of ancient trade, maritime transport, and a culture deeply reliant on the sea.

The origins of the amphora stretch back far beyond the Romans, with precedents found in Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece as early as the second millennium BCE. These early vessels, often found in archaeological sites, were used for storing and transporting liquids and grains. Over time, their shape evolved, influenced by the cultures that employed them. The Phoenicians, renowned mariners and traders, were particularly adept at refining the amphora’s design for long-distance voyages.

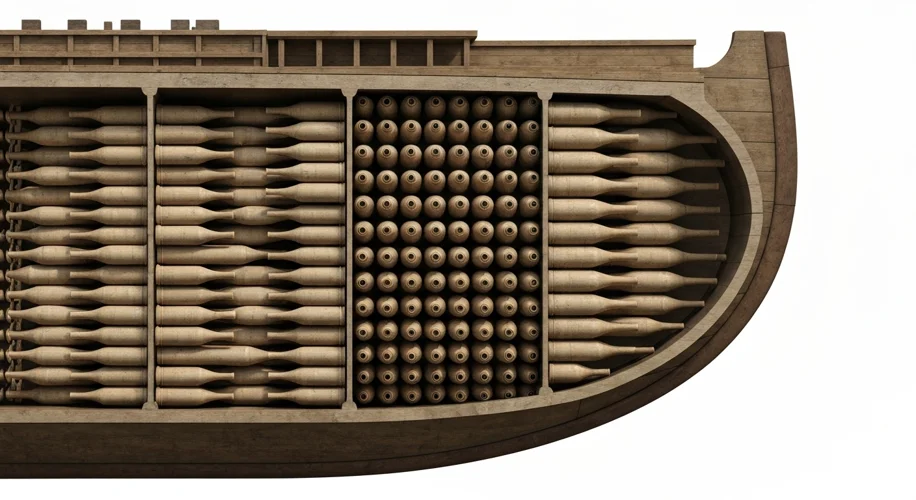

The pointed base, a seemingly awkward feature for upright display, served several crucial practical purposes. Firstly, in maritime transport, the pointed shape allowed amphorae to be packed tightly and securely into the hull of a ship. They could be wedged together, preventing them from shifting and crashing against each other during rough seas. This stability was paramount for minimizing breakage and ensuring that valuable cargo arrived at its destination intact.

Imagine a ship’s hold packed with hundreds, even thousands, of these vessels. The pointed bottoms would nestle into the spaces between others, creating a solid, interlocking mass. This efficient packing maximized the cargo capacity of each ship, a critical factor when every cubic meter of space represented potential profit. A flat-bottomed amphora, by contrast, would leave awkward gaps, reducing the overall volume of goods that could be transported.

Secondly, the pointed base made them easier to handle by dockworkers. While they couldn’t stand upright on their own, they could be easily gripped by specialized stands or simply jammed into sand or soft earth for temporary storage on land. This allowed for quick loading and unloading, crucial for the fast-paced trade of the ancient world.

Furthermore, the shape influenced the contents. A pointed base, often coupled with a narrower neck, helped to minimize the surface area exposed to air. This was particularly important for preserving the quality of liquids like wine and olive oil, protecting them from oxidation and spoilage. The tapering shape also meant less wasted space at the bottom, ensuring that even the last drops of precious liquid could be easily accessed.

The vastness of the Roman Empire, stretching from Britain to North Africa and the Middle East, depended on a complex network of trade routes. Amphorae were the workhorses of this network. Their standardization, though not absolute, allowed for a degree of predictability in trade. Archaeologists can often pinpoint the origin and even the approximate date of an amphora by its size, shape, fabric (the type of clay used), and any stamps or inscriptions it bears.

For instance, Dressel 1 amphorae, prevalent in the late Roman Republic and early Empire, are strongly associated with the transport of wine from Italy. Later types, like the African Red Slip amphorae, indicate the movement of grain and other commodities from North Africa. The sheer volume of amphorae unearthed at archaeological sites speaks volumes about the scale of ancient trade and the indispensable role these vessels played.

Their story doesn’t end with their contents. Once emptied, amphorae were often repurposed. They might be broken and used as a form of rudimentary ballast in ships, or their sherds (fragments) could be used in construction, particularly as a lightweight aggregate in Roman concrete, contributing to the longevity of structures like the Pantheon. Their ubiquity even led to their use as grave markers or as simple containers in everyday domestic life.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE didn’t spell the end of the amphora. Its design principles continued to influence pottery and container making, and variations persisted in various forms throughout the Byzantine period and into the Middle Ages. However, the era of its greatest prominence, as the primary vehicle for the economic and cultural exchange that defined the Roman world, had passed.

So, the next time you see an image of ancient ruins or read about Roman trade, spare a thought for the humble amphora. Its pointed bottom, so seemingly impractical at first glance, was a stroke of genius – a perfect marriage of form and function that enabled the vast, interconnected world of antiquity to thrive. It’s a silent testament to the enduring ingenuity of human hands and minds, a powerful reminder that even the most utilitarian objects can carry the weight of history.