The embers of World War II had barely cooled when the defeated nations found themselves under the watchful eyes of the victors. But the path of occupation, meant to guide these countries toward peace and stability, was anything but uniform. In the ashes of a global conflagration, the stories of occupied Germany, Korea, and Japan unfolded with vastly different strategies, reflecting the complex geopolitical currents of the era.

A Continent Divided: Germany’s Fourfold Burden

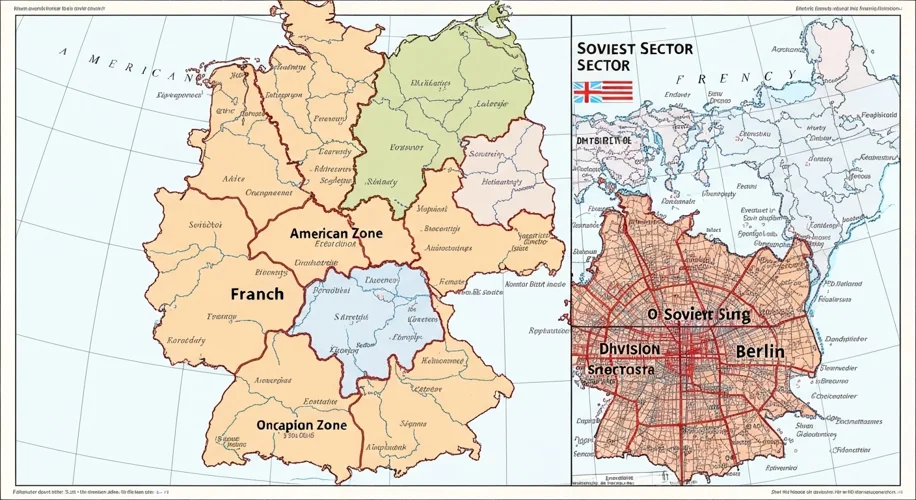

Germany, the epicenter of the European war, bore the most intricate occupation. The Yalta Conference in February 1945, even before the war’s end, had already determined that Germany would be divided into four zones of occupation. The victorious powers – the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and France – each carved out a slice of the defeated nation. This decision was born from a mixture of necessity and a deep-seated mistrust, particularly between the Western Allies and the burgeoning Soviet Union.

The immediate goals were clear: demilitarization, denazification, and democratization. However, the ideological chasm between the capitalist West and the communist East rapidly widened. As the Cold War solidified its grip, these zones began to diverge. In the West, under American leadership, efforts focused on rebuilding democratic institutions, fostering economic recovery through initiatives like the Marshall Plan, and integrating West Germany into the Western alliance. The objective was to prevent a resurgence of militarism and Nazism while creating a bulwark against Soviet influence.

Meanwhile, in the Soviet zone, the emphasis was on reparations and establishing a socialist state aligned with Moscow. The dismantling of industries and the imposition of a communist political system set East Germany on a starkly different trajectory. The division of Germany was not merely a military arrangement; it became a profound ideological and physical split, culminating in the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, a stark symbol of the Iron Curtain.

A Peninsula Torn: Korea’s Dual Mandate

Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945 was a moment of immense national hope. However, this hope was quickly tempered by the division of the peninsula along the 38th parallel. Like Germany, Korea was initially divided into two zones of occupation: the North by the Soviet Union and the South by the United States. This division was, in part, a pragmatic military decision to oversee the surrender of Japanese forces, but it quickly hardened into a political frontier.

The differing ideologies and objectives of the American and Soviet occupiers soon led to the establishment of two separate states: the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) in the North, backed by the Soviets, and the Republic of Korea (ROK) in the South, supported by the Americans. The Korean War (1950-1953) that followed was a brutal manifestation of this division, a proxy conflict that cemented the peninsula’s split and left a legacy of tension that persists to this day.

The Dragon Under One Wing: Japan’s Singular Occupation

In stark contrast to Germany and Korea, Japan’s post-war occupation was largely a singular effort, led predominantly by the United States under General Douglas MacArthur. While other Allied powers had a role, American influence was paramount. The decision for a single-power occupation stemmed from several factors: Japan’s swift and unconditional surrender, the desire for a unified and efficient pacification process, and the American vision for a remade Japan.

The American occupation of Japan, which lasted from 1945 to 1952, was characterized by a dual strategy: what Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP) General MacArthur termed “demilitarization and democratization.” This involved dismantling Japan’s military, prosecuting war criminals, and implementing sweeping reforms. A new constitution was drafted, renouncing war and establishing a parliamentary democracy. Land reforms were enacted, empowering farmers, and efforts were made to break up the zaibatsu, the powerful family-controlled industrial conglomerates.

Unlike Germany, where the victor powers were deeply divided, the American occupation of Japan aimed for a more cohesive transformation. The goal was to transform Japan from a militaristic aggressor into a peaceful, democratic nation that could serve as a stable ally in the Pacific. While there were critics and certainly challenges, the relative speed and focus of the American occupation left a distinct imprint on modern Japan.

Divergent Paths, Shared Histories

The post-World War II occupations of Germany, Korea, and Japan offer a compelling study in contrasts. Germany’s four-power occupation, fractured by the onset of the Cold War, led to a deep and enduring division. Korea’s initial dual occupation, mirroring Germany’s fate, erupted into a devastating war that froze its division. Japan, under a predominantly American occupation, underwent a rapid and profound transformation. These divergent legacies underscore how the geopolitical realities, the nature of the defeat, and the objectives of the occupying powers sculpted the destinies of these nations in the crucible of the post-war world.