The year is 1898. The United States, a nation forged in the fires of revolution against colonial rule, stands at a precipice. The Spanish-American War has ended, leaving Spain’s empire in tatters and the Philippines, an archipelago rich in history and culture, newly acquired by the American eagle.

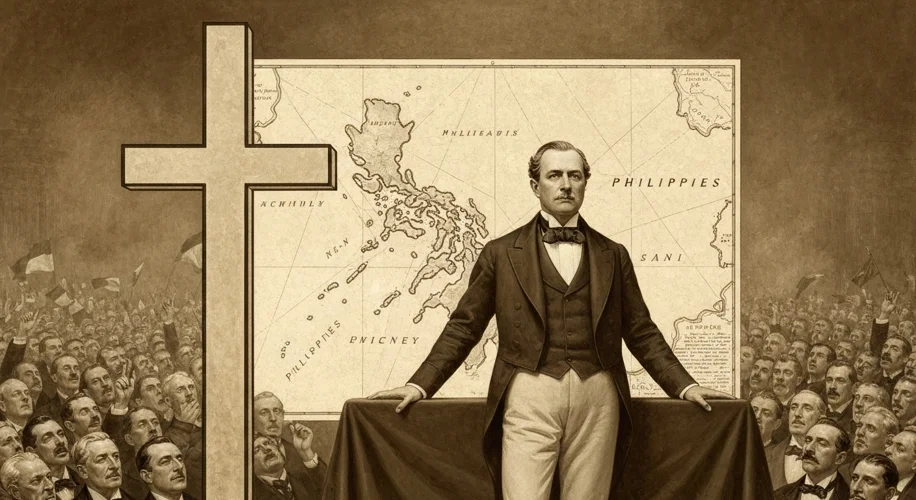

President William McKinley, a man who famously wrestled with his conscience over this decision, declared his rationale with a conviction that echoed through the halls of power: “We must uplift, civilize, and Christianize them.”

But here lies a profound irony, a historical twist that still makes us pause. By 1898, the vast majority of the Filipino people, over 80%, were devout Catholics. They had been for centuries, thanks to the long and often brutal Spanish colonial period. So, what did McKinley’s “divine mission” truly entail? Was it a genuine desire to spread Christianity, or a convenient justification for a burgeoning imperial ambition?

Let’s rewind to understand the context. The late 19th century was the zenith of European imperialism. Nations across Europe were carving up Africa and Asia, driven by a complex mix of economic greed, strategic advantage, and a pervasive belief in their own cultural superiority – the so-called “White Man’s Burden.” America, eager to assert its place on the world stage, was not immune to these powerful currents.

The Spanish-American War, ostensibly fought to liberate Cuba from Spanish oppression, quickly expanded. The Battle of Manila Bay in May 1898 saw Commodore George Dewey’s American Asiatic Squadron decisively defeat the Spanish fleet. This swift victory presented the U.S. with a prize far beyond its initial intentions. Suddenly, the fate of the Philippines, a nation with its own burgeoning independence movement led by Emilio Aguinaldo, was in American hands.

McKinley’s internal struggle is well-documented. He reportedly prayed for guidance, and the answer, he claimed, came in the form of a divine revelation: the U.S. had a duty to take possession of the Philippines and govern them. This spiritual mandate, however, conveniently aligned with the strategic and economic interests of the time. The islands offered a gateway to the lucrative markets of Asia, a coaling station for the U.S. Navy, and a symbol of America’s growing global power.

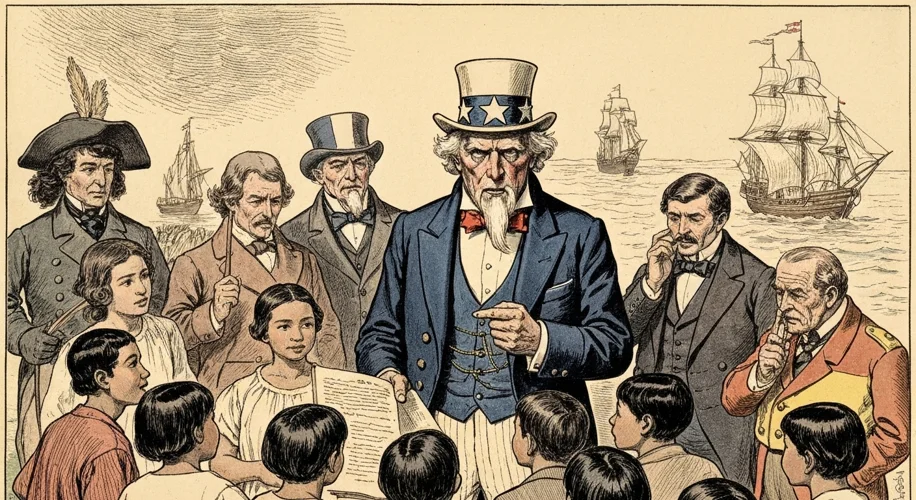

The reality on the ground painted a different picture than McKinley’s pious pronouncements. While American missionaries did follow the soldiers, their efforts were often met with indifference or outright resistance by a population already steeped in Catholic traditions. The American Protestant mission, in many ways, arrived as an unwelcome guest to a predominantly Catholic home. The focus on “Christianization” began to shift, subtly or overtly, towards Americanization – imposing American language, culture, and governance.

The consequences were far from peaceful. The Filipino people, who had fought for their own independence from Spain, found themselves in a new war, this time against their supposed liberators. The Philippine-American War, lasting from 1899 to 1902, was a brutal conflict marked by fierce resistance and significant American military action. Reports of atrocities, scorched-earth tactics, and the suppression of Filipino nationalism cast a long shadow over the proclaimed benevolent intentions.

Historians have long debated the true motivations behind the annexation. Was it truly a “divine mission,” an act of accidental imperialism, or a calculated step towards becoming a global power? The evidence suggests a complex interplay of factors. The economic and strategic advantages were undeniable. The prevailing racial and cultural attitudes of the era certainly played a role, fostering a belief that Americans were uniquely suited to govern and uplift the Filipinos.

The “Christianization” narrative, in this light, appears less as a primary objective and more as a rhetorical tool, a way to legitimize an imperial project to both a domestic audience and the international community. It allowed the U.S. to frame its expansion not as conquest, but as a moral crusade.

The legacy of this period is complex. While the U.S. did introduce reforms in education, infrastructure, and governance, the imposition of foreign rule and the subsequent conflict left deep scars. The very rationale of spreading Christianity to a predominantly Catholic nation remains a stark reminder of how easily notions of divine purpose can be twisted to serve the ambitions of empire. It forces us to ask: when a nation claims a “divine mission” to civilize others, whose definition of civilization are we truly following, and at what cost?

The McKinley Tariff, a separate but contemporaneous piece of legislation that significantly raised tariffs on imported goods, also played a role in the economic considerations surrounding colonial expansion, as it aimed to protect American industries and create new markets for American goods. While not directly related to the stated religious mission, it underscores the broader economic imperatives driving U.S. foreign policy at the time. The Philippines, with its potential as both a market and a source of raw materials, fit neatly into this economic strategy.

Ultimately, the story of the Philippines and President McKinley’s rationale is a cautionary tale. It highlights the enduring tension between a nation’s proclaimed ideals and its actual actions, especially when those actions involve power, territory, and the complex intersection of faith and foreign policy.