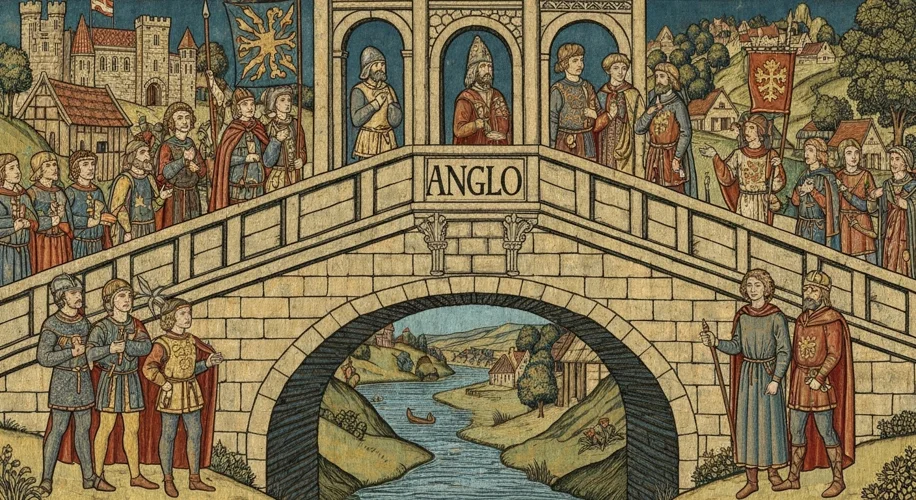

The year 1066. A date etched into the memory of England, synonymous with a cataclysmic shift in power: the Norman Conquest. William the Conqueror, Duke of Normandy, landed on English soil, claimed the throne, and ushered in an era of profound change. The ruling elite, the language, the very fabric of society were reshaped by French influence. Yet, amidst this seismic upheaval, a curious linguistic survivor persisted: the term ‘Anglo’. Why, after such a dramatic imposition of a new order, did the old name for the English people and their land continue to resonate?

The Norman Conquest was not merely a change of kings; it was a cultural and linguistic bombardment. The Norman French became the language of the court, law, and administration, gradually overlaying and intermingling with the Old English spoken by the majority. For a time, French was the language of power, while English was relegated to the common folk, viewed as the tongue of the vanquished.

One might expect the victors to have imposed their own nomenclature universally, erasing the “Anglo-Saxon” identity. Indeed, Norman names and titles became prevalent, and the concept of “England” itself was redefined through a Norman lens. However, the persistence of ‘Anglo’ reveals a more complex reality. It wasn’t a simple case of obliteration; it was a story of adaptation, resilience, and the slow, intricate weaving of two cultures.

The survival of ‘Anglo’ can be attributed to several key factors. Firstly, the sheer numerical majority of the Anglo-Saxon population meant their language and identity could not be entirely expunged. Even as French permeated the upper echelons, the vast majority of the populace continued to speak English. This linguistic bedrock provided a fertile ground for the continued use of ‘Anglo’ as a descriptor.

Secondly, the Normans themselves, while conquerors, were not entirely alien. They were Vikings who had settled in France, adopting its language and customs. Upon conquering England, they began a process of assimilation, intermarrying with the Anglo-Saxon nobility and gradually adopting aspects of English culture. This made the complete eradication of the ‘Anglo’ identity less feasible and perhaps less desirable as they consolidated their rule.

Furthermore, the term “Anglo” was not merely a linguistic marker; it carried historical and cultural weight. It represented centuries of development, a shared heritage, and a distinct sense of self. To simply discard it would have been to ignore the very land and people they now ruled. Therefore, ‘Anglo’ continued to be used in various official and unofficial capacities, often in conjunction with Norman terms, creating a hybrid identity.

Consider the ‘Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’, a vital historical record. While the Normans held sway, the Chronicle continued to be compiled and updated, albeit with a Norman perspective creeping in over time. This demonstrates a continuity of narrative and self-identification, where ‘Anglo’ remained a significant part of the historical self-portrait.

Even in legal and administrative contexts, the Anglo-Saxon legal system, while modified, retained many of its core principles. The concept of ‘Anglo-Saxon law’ persisted, underscoring the deep roots of the preceding culture. In scholarly or ecclesiastical circles, distinguishing between the Norman rulers and the broader populace, or referring to the land itself, the term ‘Anglo’ provided a necessary and convenient shorthand.

The Norman Conquest was a watershed moment, undeniably transforming England. However, history rarely operates in absolute black and white. The persistence of ‘Anglo’ is a testament to the enduring power of identity, language, and culture. It highlights how even under the most forceful of impositions, the old ways do not simply vanish but often adapt, blend, and continue to shape the new. The term ‘Anglo’ thus became a symbol of this complex fusion, a reminder that the England that emerged from 1066 was not solely Norman, but a rich, evolving tapestry woven from both conqueror and conquered.

In essence, the story of ‘Anglo’ after the Norman Conquest is a microcosm of how societies grapple with profound change. It speaks to the resilience of the common people, the pragmatic adaptations of the ruling class, and the inherent difficulty of erasing deeply ingrained cultural identities. The echo of ‘Anglo’ persisted not because the Normans forgot their victory, but because the English themselves never entirely forgot who they were, ensuring that their name, like their language, would endure.