History is littered with the ghosts of innovations that promised the moon but delivered little more than dust. These were the “next big things,” the paradigm shifts, the game-changers that, in hindsight, often seem more like historical footnotes or even cautionary tales. From the flying cars of yesterday to the blockchain fantasies of today, the allure of the revolutionary has always been potent, yet the reality often falls flat.

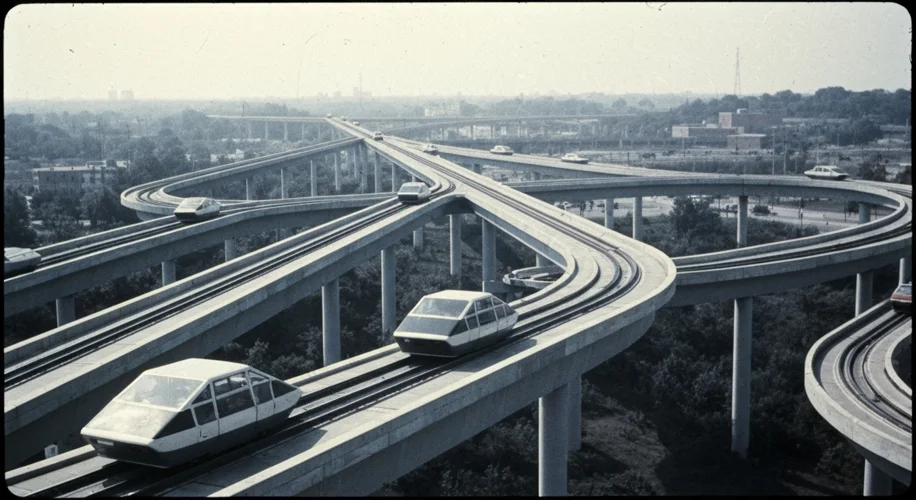

Consider the case of the Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) systems, particularly their heyday in the 1970s. Imagine sleek, automated pods gliding silently along elevated tracks, whisking you directly to your destination without stops or delays. This wasn’t just a sci-fi fantasy; it was hailed by many as the urban transportation solution of the future. Proponents envisioned cities free from traffic jams, with clean, efficient, and personalized travel.

One of the most prominent examples was the Morgantown PRT system in West Virginia. Launched in 1975, it was a pioneering effort, a joint venture between the U.S. Department of Transportation and West Virginia University. The system featured a fleet of small, driverless electric vehicles that ran on a network of elevated guideways. It was a technological marvel for its time, designed to alleviate the parking and traffic woes of the university campus and the city.

The initial reception was enthusiastic. Here was a tangible glimpse into a future of effortless commuting. The technology was innovative, aiming to be both environmentally friendly and highly efficient. The vision was compelling: a network of personalized transit, offering an on-demand service that could rival the convenience of private cars while reducing congestion and pollution. It was the “next big thing” in urban mobility.

However, the dream of widespread PRT adoption soon encountered the harsh realities of economics, engineering, and public acceptance. The Morgantown system, while functional, proved to be incredibly expensive to build and maintain. The intricate network of guideways and the specialized vehicles required significant ongoing investment. Furthermore, the system struggled to scale up to serve larger metropolitan areas, a crucial requirement for a truly transformative urban transit solution.

The technological sophistication that made PRT appealing also made it susceptible to glitches and costly repairs. The automated nature, while intended to increase efficiency, also meant that any malfunction could bring sections of the system to a grinding halt. For cities considering similar investments, the high upfront costs, coupled with the demonstrated operational challenges and limited scalability, presented a significant barrier.

Beyond the practicalities, PRT systems faced a cultural hurdle. While the idea of individual pods was attractive, it often failed to account for the social aspect of public transportation. People are accustomed to the communal experience of buses and trains, and the isolating nature of a personal pod didn’t resonate with everyone. Moreover, the visual impact of extensive elevated guideways in urban landscapes was often seen as intrusive and aesthetically unappealing, leading to public resistance.

Many other PRT projects proposed in the late 20th century never moved beyond the planning stages or were abandoned after initial trials. The promise of a clean, efficient, and personalized transit system, once heralded as the future, largely remained confined to a few select locations, with Morgantown being one of the most enduring, yet hardly ubiquitous, examples.

What can we learn from the fate of PRT and similar overhyped innovations? It highlights the critical gap between a compelling vision and its practical realization. Technology alone is rarely enough; it must be economically viable, scalable, socially acceptable, and adaptable to the complex realities of human behavior and urban environments.

The allure of the “next big thing” continues to drive innovation, but history teaches us a valuable lesson: many promising futures fail to materialize. The ghosts of these flopped innovations serve as a constant reminder that while ambition is essential, a healthy dose of realism and a deep understanding of context are crucial for any innovation to truly change the world.

From the electric cars of the early 20th century that were quickly overshadowed by gasoline engines, to the dirigible airships that once promised to revolutionize travel before the advent of the airplane, the annals of history are replete with such examples. Each failure, however, contributes to our collective knowledge, refining our understanding of what it takes for an idea to transition from a futuristic dream to an everyday reality.