The year is 1956. The world is still reeling from the Second World War, a new bipolar order is solidifying, and the embers of colonialism are flickering, threatening to ignite. In this volatile landscape, a single event, sparked by the nationalization of a vital waterway, would send shockwaves across the globe, fundamentally altering the balance of power and heralding the twilight of European imperial might.

The Spark: A Canal, A President, A Plan

At the heart of the unfolding drama lay the Suez Canal, an artificial marvel of engineering completed in 1869. This 101-mile ribbon of water, cutting through Egypt, was a crucial artery for global trade, especially for oil shipments between Europe and the Middle East. Its ownership and management, however, were largely controlled by the British and French through the Universal Suez Canal Company. For Egypt, under the charismatic leadership of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, this represented a stark symbol of foreign domination.

Nasser, a fervent Arab nationalist, sought to bolster Egypt’s standing and fund the ambitious Aswan High Dam project, a monumental undertaking designed to transform the Egyptian economy. When the United States and Britain, who had previously pledged financial support for the dam, abruptly withdrew their offers, Nasser saw it as a deliberate attempt to undermine his vision. His response was audacious and defiant: on July 26, 1956, he announced the nationalization of the Suez Canal, declaring that its revenues would now fund the dam.

The Conspiracy: A Secret Alliance is Forged

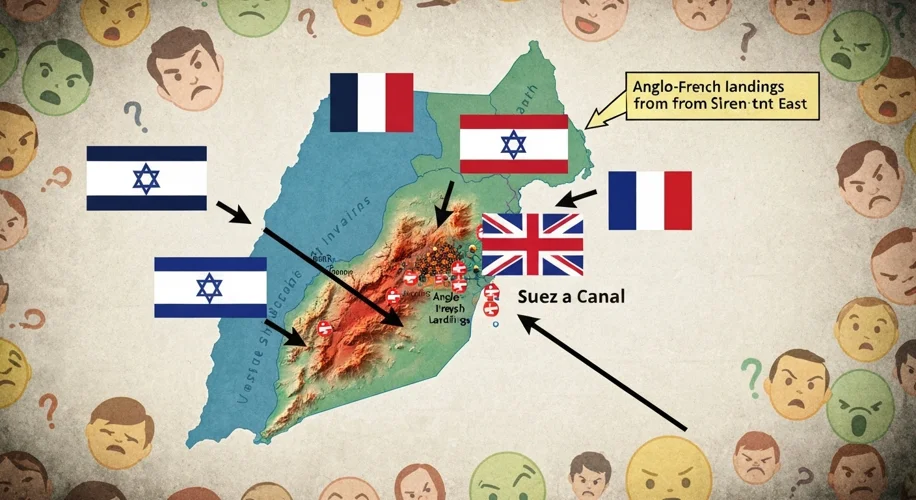

The nationalization sent shockwaves through London and Paris. For British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, it was a direct challenge to Britain’s prestige and a potential threat to its oil supplies. France, still smarting from its defeat in the First Indochina War and facing a fierce Algerian uprising, viewed Nasser as a dangerous sponsor of anti-French forces. Secretly, a plan began to form between Britain, France, and Israel, a nation that felt increasingly threatened by Nasser’s rhetoric and military build-up.

The tripartite plan was deceptively simple: Israel would invade the Sinai Peninsula, citing security concerns. Britain and France would then issue an ultimatum to both sides to withdraw from the canal, and when (as they anticipated) Egypt refused, they would intervene militarily, ostensibly to protect the canal and restore order. This intervention would also serve to depose Nasser, whom they viewed as a destabilizing force.

The Invasion: A Swift, Brutal Onslaught

On October 29, 1956, Israel launched its invasion of the Sinai. Within days, Israeli forces had achieved significant battlefield victories. As per the plan, Britain and France issued their ultimatum, which was predictably rejected by Egypt. On October 31, British and French aircraft began bombing Egyptian airfields, crippling Nasser’s air force. Paratroopers then landed near the canal, followed by naval landings.

The military operation was, in many ways, a success for the invading forces. They quickly secured positions around the canal, and the Egyptian military, despite fierce resistance in some areas, was overwhelmed. However, the diplomatic and political fallout was immediate and catastrophic.

The World Reacts: A Storm of Condemnation

The international community was aghast. The United States, caught completely off guard by its allies’ actions, was furious. President Dwight D. Eisenhower viewed the invasion as a blatant act of colonial aggression that undermined his efforts to win over newly independent nations in the Middle East. He feared it would drive Arab nations into the arms of the Soviet Union.

The Soviets, eager to exploit the situation, issued veiled threats of intervention and condemned the Anglo-French action. The United Nations was also deeply divided, but a strong consensus emerged against the invasion. Public opinion in many countries, including within Britain and France, turned against the war, with widespread protests and condemnation.

Faced with overwhelming international pressure, particularly from the United States, Britain and France were forced to halt their military operations. Under UN supervision, a ceasefire was declared, and the invading forces eventually withdrew.

The Aftermath: A New World Order Emerges

The Suez Crisis of 1956 was a watershed moment. For Britain and France, it was a humiliating denouement, effectively marking the end of their Great Power status and their ability to act independently on the global stage without American approval. Their colonial ambitions were irrevocably shattered, and their influence in the Middle East was severely diminished.

For President Nasser, despite the military defeat, it was a profound political victory. He emerged as a hero and a symbol of Arab nationalism, further solidifying his leadership within Egypt and across the Arab world. The crisis also underscored the growing power of the United States and the Soviet Union, demonstrating that any major international conflict could not be resolved without their consent. It accelerated the decolonization process and contributed to the rise of the Non-Aligned Movement.

The Suez Crisis was more than just a military conflict over a waterway; it was a seismic shift in global politics. It exposed the waning power of old empires, highlighted the emergence of new superpowers, and reshaped the geopolitical landscape for decades to come. The echoes of this pivotal event continue to resonate, reminding us of the complex interplay of nationalism, power, and the enduring struggle for self-determination.