The Aegean Sea, a sapphire jewel nestled between Europe and Asia, has cradled civilizations as ancient and profound as the myths they inspired. Among these, the Minoan civilization, flourishing on the island of Crete during the Bronze Age (roughly 2700 to 1450 BCE), stands as a testament to human ingenuity, artistic brilliance, and a society that seemed to exist in a world of its own making. Their palaces, adorned with vibrant frescoes, their intricate pottery, and their enigmatic Linear A script paint a picture of a sophisticated culture that thrived for over a millennium, only to vanish with a sudden, catastrophic abruptness that still echoes through time.

Imagine Crete, not as the sun-drenched tourist destination of today, but as a bustling hub of a civilization that mastered the seas. The Minoans, named by the archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the legendary King Minos of labyrinthine fame, were a maritime people. Their wealth was built on trade, their ships sailing across the Mediterranean, connecting Crete with Egypt, the Near East, and the Aegean islands. They were not a warrior culture in the traditional sense; their palaces, like the magnificent sprawling complex at Knossos, lacked formidable defensive walls. Instead, their security seems to have been a byproduct of their naval prowess and the perceived peace of their island haven.

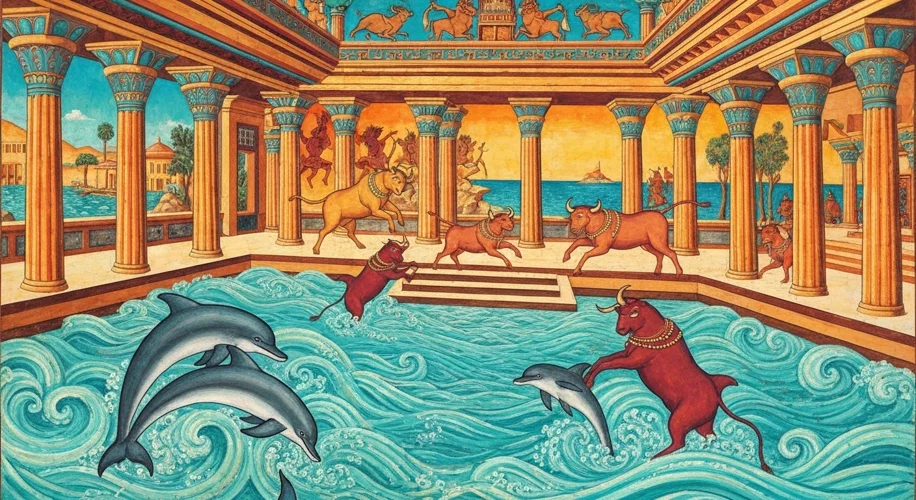

The Minoans were artists. Their frescoes are a riot of color and movement, depicting scenes of nature – dolphins dancing, lilies blooming, monkeys scampering – and ritualistic activities, most famously the athletic prowess of bull-leapers. These figures, depicted with slender waists and dynamic poses, seem to defy gravity as they somersault over charging bulls. This imagery suggests a society deeply connected to the natural world, one that perhaps viewed the bull not just as an animal, but as a powerful symbol of fertility and strength, even divinity. Their palaces were not just residences; they were centers of administration, religious activity, and artistic production. The labyrinthine corridors of Knossos, with their sophisticated plumbing systems and brightly painted walls, speak of advanced engineering and a keen aesthetic sensibility.

But this thriving world, seemingly so secure and radiant, was vulnerable. The very earth beneath their feet held a dormant fury. To the north of Crete lies the volcanic island of Thera (modern-day Santorini). Around 1600 BCE, Thera experienced one of the most violent volcanic eruptions in human history. The sheer scale of the eruption was cataclysmic. Vast quantities of ash and pumice were ejected into the atmosphere, darkening the skies and raining down upon the surrounding region. The eruption triggered massive pyroclastic flows, superheated clouds of gas and debris that swept across the island, obliterating everything in their path.

The immediate aftermath of the eruption was devastating for Crete. The immense blast sent colossal tsunamis racing across the Aegean. These colossal waves, tens or even hundreds of feet high, would have slammed into the shores of Crete, inundating coastal settlements, destroying harbors, and devastating the Minoan fleet that formed the backbone of their economy and defense. Imagine the terror of those living near the coast as the sea receded unnaturally, only to return with unimaginable force, sweeping away homes, temples, and lives.

The impact was not just physical; it was existential. The eruption and subsequent tsunamis crippled the Minoan civilization. Their intricate trade networks were shattered, their coastal settlements destroyed, and their agricultural lands potentially ruined by ashfall and saltwater intrusion. While the eruption is the most dramatic event, it’s crucial to understand that it may not have been the sole cause of their decline. The Minoans had weathered natural disasters before. However, the sheer magnitude of the Thera eruption, combined with possible internal factors or other environmental stresses, pushed them past their breaking point.

Following the eruption, Crete shows signs of significant disruption. While some settlements were rebuilt, they were often smaller and less elaborate. The grand palaces, once symbols of power and prosperity, were largely abandoned or repurposed. The distinctive Minoan culture began to wane, gradually replaced by the influence of the Mycenaeans, a mainland Greek culture that rose to prominence in the subsequent centuries. By around 1450 BCE, Minoan Crete was largely under Mycenaean control, and the unique Minoan civilization, as it had existed, effectively ceased to be.

The story of the Minoans is a potent reminder of the fragility of even the most advanced societies. It highlights how a single, natural event, no matter how distant, can have cascading consequences that reshape history. The Minoans, who created such beauty and order, were ultimately humbled by the raw power of nature. Their sudden disappearance, a mystery that has captivated historians and archaeologists for generations, serves as a dramatic illustration of how civilizations can rise, flourish, and then, in the blink of an eye, become mere echoes in the sands of time.

Their legacy, however, is not entirely lost. The art, the architecture, and the very idea of a sophisticated Bronze Age Aegean civilization endure. The Minoans, in their silent ruins, continue to whisper tales of a world that was, a world that achieved so much, only to be swept away by the tempestuous fury of the earth and sea. They are a vibrant chapter in the grand, ongoing narrative of human history, a story of creation, peak, and ultimately, a profound and sudden end.