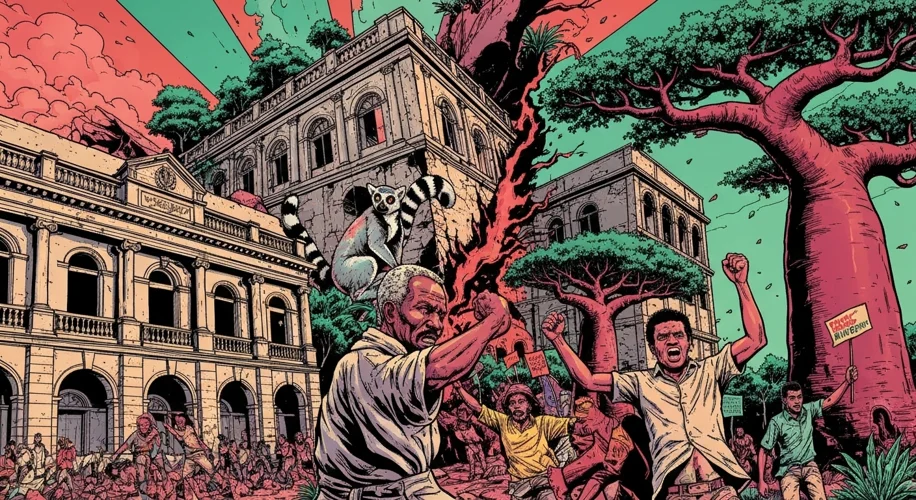

The island nation of Madagascar, a land of unique biodiversity and a rich cultural tapestry, has once again found itself at a political crossroads. The recent ousting of President [President’s Name – replace with actual name if known, otherwise use placeholder] in a military coup, following weeks of intense youth-led protests, is not an isolated incident but rather a stark reminder of the nation’s long and complex history of political instability, deeply rooted in its colonial past and ongoing struggles for self-determination.

Madagascar’s story is one of ancient origins, settled by seafaring peoples from Borneo thousands of years ago. Over centuries, a unique Malagasy culture emerged, a blend of Austronesian and African influences, characterized by a reverence for ancestors (famadihana, or the “turning of the bones,” being a notable ritual) and a complex system of social and political organization.

The arrival of European powers in the 16th century marked a significant turning point. Initially a stopover for traders and pirates, Madagascar’s strategic location in the Indian Ocean soon attracted the attention of colonial ambitions. France, in particular, asserted its dominance, eventually colonizing the island in the late 19th century. The colonial era, spanning from 1896 to 1960, brought profound changes. While it introduced some modern infrastructure and administrative systems, it also exploited the island’s resources, suppressed local traditions, and imposed a foreign political order. This period sowed the seeds of resentment and a deep-seated desire for independence.

Following World War II, a wave of decolonization swept across Africa and Asia. Madagascar, then known as the Malagasy Republic, gained its independence from France on June 26, 1960. However, the euphoria of freedom was soon tempered by the challenges of nation-building and the lingering influence of its former colonial power. The post-independence era has been a tumultuous journey, marked by a series of political upheavals, coups, and periods of authoritarian rule. The First Republic, led by Philibert Tsiranana, eventually gave way to a more socialist-oriented regime under Didier Ratsiraka in 1975. His rule, characterized by a strongman approach, lasted for 18 years, punctuated by economic hardship and political repression.

The winds of change blew again in the early 1990s, leading to a return to multi-party democracy. However, this transition was far from smooth. The early 21st century witnessed further political crises, including the controversial election of Marc Ravalomanana in 2002 and the subsequent military-backed takeover by Andry Rajoelina in 2009, an event that significantly damaged Madagascar’s international standing and economic development.

The recent events, culminating in the current political crisis, highlight a recurring pattern: a disconnect between the ruling elite and the populace, exacerbated by economic disparities and a perceived lack of accountability. The youth, who form a significant portion of Madagascar’s population, have emerged as a powerful force, their frustration channeled into sustained protests. Their demands often echo long-standing grievances, including calls for better governance, economic opportunities, and an end to corruption.

The cycle of political instability has had a profound impact on Madagascar. Its rich natural resources and tourism potential remain largely underdeveloped, hampered by the instability that deters foreign investment and disrupts economic activity. The nation consistently ranks among the poorest in the world, with a large segment of its population living in extreme poverty, despite the island’s natural wealth.

Understanding Madagascar’s political landscape requires acknowledging the interplay of internal dynamics and external influences. The legacy of French colonialism continues to cast a long shadow, with debates often surfacing about the extent of ongoing French influence and the nature of international partnerships. Moreover, the country’s unique biodiversity, while a source of national pride, also makes it a target for foreign interests in natural resource extraction, a factor that can further complicate political stability.

The current situation underscores a critical question for Madagascar: can it break free from this cycle of political turmoil and forge a path towards sustained development and democratic stability? The answer likely lies in addressing the root causes of discontent: fostering inclusive governance, promoting economic equity, strengthening democratic institutions, and ensuring accountability for those in power. The energy and determination displayed by the youth protesters offer a glimmer of hope, but the true test will be in their ability to translate their demands into lasting political and social change.

Madagascar’s journey is a testament to the resilience of its people and the enduring spirit of a nation striving to chart its own course, free from the historical chains of colonialism and the persistent specter of political instability. The echoes of its past continue to shape its present, and its future hinges on its ability to learn from these tumultuous tides and build a more stable and prosperous tomorrow.