The year is 1918. The world is locked in the brutal embrace of the First World War, a conflict that has already claimed millions of lives. But as nations bled on the battlefields, an even more insidious enemy was silently gaining ground, an enemy that knew no borders, recognized no flags, and spared no one. This was the H1N1 influenza virus, a microscopic killer that would soon become known as the Spanish Flu, and its impact would be more devastating than any war.

The stage was set for a global catastrophe. Soldiers were packed into crowded trenches, barracks, and transport ships, creating ideal conditions for a highly contagious respiratory virus to spread like wildfire. In many parts of the world, especially in the Allied and Central Powers, news of the outbreak was suppressed to maintain morale. This deliberate censorship, ironically, led to the pandemic being misnamed the ‘Spanish Flu’ because neutral Spain, with its uncensored press, was one of the first to report on the severity of the illness.

The first wave, appearing in the spring of 1918, was relatively mild, causing symptoms akin to a common flu. Many believed the worst was over. However, this was merely a deceptive calm before the storm. In the late summer and fall of 1918, the virus mutated into a far more virulent form. This second wave was unlike anything seen before. It struck with terrifying speed and ferocity, attacking not just the elderly and the very young, but also healthy young adults – the very demographic fighting on the front lines.

Eyewitness accounts paint a grim picture. Dr. Loring Miner, a physician in Sangamon County, Illinois, wrote of the devastating second wave: “The disease is like a cyclone. People go to bed well, and they wake up dead.” Symptoms were horrific: high fever, severe body aches, and a terrifying blue discoloration of the skin caused by a lack of oxygen. In many cases, the lungs would fill with fluid, leading to suffocation. Doctors and nurses, often falling ill themselves, worked tirelessly in makeshift hospitals, overwhelmed by the sheer number of the sick and dying. The grim reaper seemed to stalk every household, every community.

Consider the timeline:

* March 1918: First cases appear, mainly among U.S. soldiers. This first wave is relatively mild.

* August-October 1918: A virulent new strain emerges, causing widespread death. This is the peak of the pandemic.

* January-March 1919: A third wave, less deadly than the second, sweeps across the globe.

* 1920: The pandemic officially subsides, leaving a world forever changed.

The impact of the Spanish Flu was profound and far-reaching. It is estimated to have infected a third of the world’s population and killed between 50 and 100 million people – more than World War I, World War II, and the Vietnam War combined. Entire communities were decimated, economies were crippled, and the social fabric of many nations was torn apart.

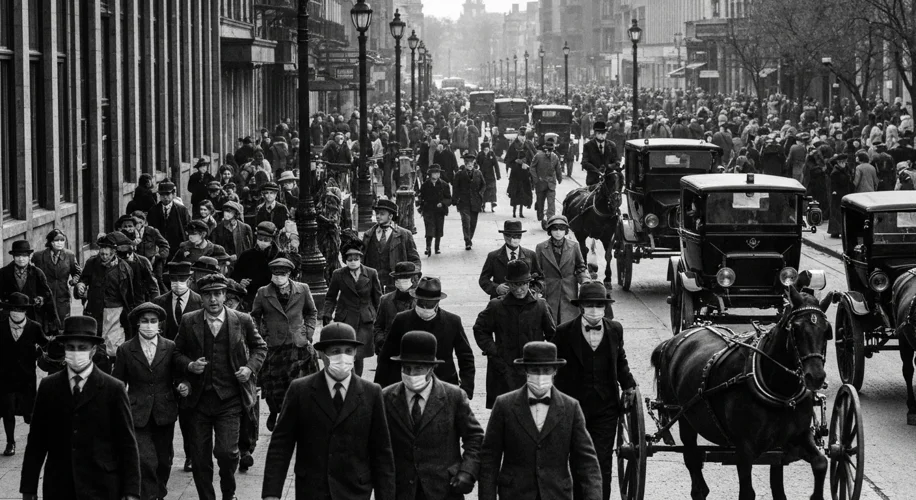

In the United States, cities like Philadelphia and St. Louis implemented drastic public health measures. Parades were canceled, businesses were shut down, and citizens were urged to wear masks and avoid public gatherings. Yet, even these measures couldn’t halt the relentless march of the virus. The sheer death toll strained mortuaries and gravediggers to their breaking point, with mass graves becoming a common sight in many cities.

The pandemic also had significant cultural and psychological effects. It instilled a deep-seated fear of contagion and a heightened awareness of human vulnerability. It spurred advancements in public health and epidemiology, leading to the establishment of health organizations and a greater understanding of infectious diseases. The experience of loss and collective trauma also found its way into art, literature, and music, as survivors grappled with the unimaginable devastation.

Why was this particular influenza strain so deadly? Scientists believe its virulence was due to a confluence of factors. The virus itself was exceptionally aggressive, and its ability to spread was amplified by the global movement of troops and civilians during the war. The immune systems of many people, already weakened by the war and malnutrition, were less able to fight off the infection. Furthermore, the virus’s tendency to cause a cytokine storm – an overreaction of the immune system – was particularly devastating to young, healthy adults whose immune systems were robust.

Looking back, the Spanish Flu serves as a stark reminder of humanity’s vulnerability to nature’s forces, even in an age of technological advancement. It underscored the critical importance of global cooperation, robust public health infrastructure, and transparent communication in the face of pandemics. The lessons learned from 1918 continue to resonate today, informing our responses to new public health crises and reminding us that the unseen enemy, though microscopic, can wield the power to reshape the very course of human history.

It’s a chilling thought: a war fought on a global scale, only to be overshadowed by an enemy invisible to the naked eye. The Spanish Flu didn’t just claim lives; it redrew the map of the world, reshaped societies, and left an indelible scar on the collective memory of humankind.