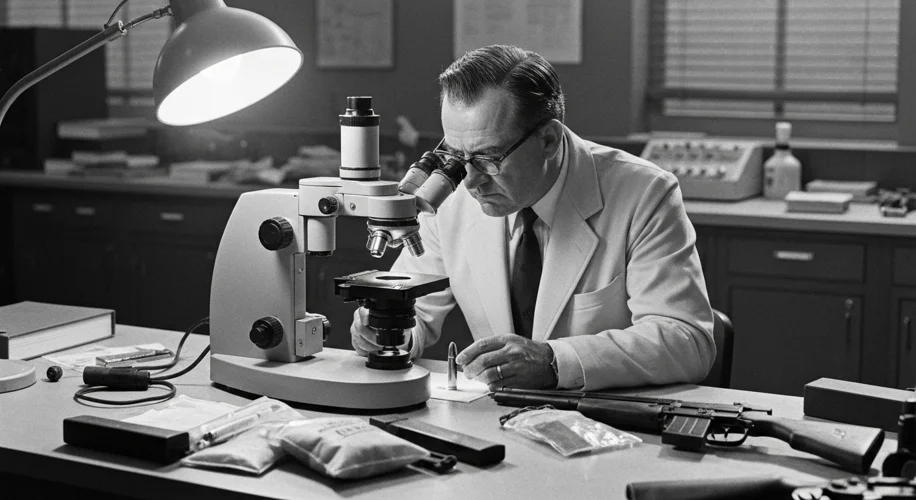

In the hushed corridors of crime scenes, amidst the chaos and despair, lie silent witnesses. These are not the distraught families or the panicked onlookers, but the minute fragments of metal, the discarded casings, the very instruments of violence that tell a chilling story. For decades, a specialized cadre of forensic scientists, the firearms examiners, have been the unsung heroes piecing together these narratives, their meticulous work often the linchpin in securing justice. Their journey is a fascinating tapestry woven into the very fabric of American law enforcement and forensic science.

The dawn of modern forensic science in the United States was a slow, often hesitant affair. Before the widespread adoption of systematic forensic techniques, investigations relied heavily on witness testimony, confession, and often, intuition. The introduction of firearms as a common tool of crime presented a unique challenge. How could investigators definitively link a bullet found at a crime scene to a specific weapon? The answer lay in the unique, almost fingerprint-like characteristics left behind by a firearm.

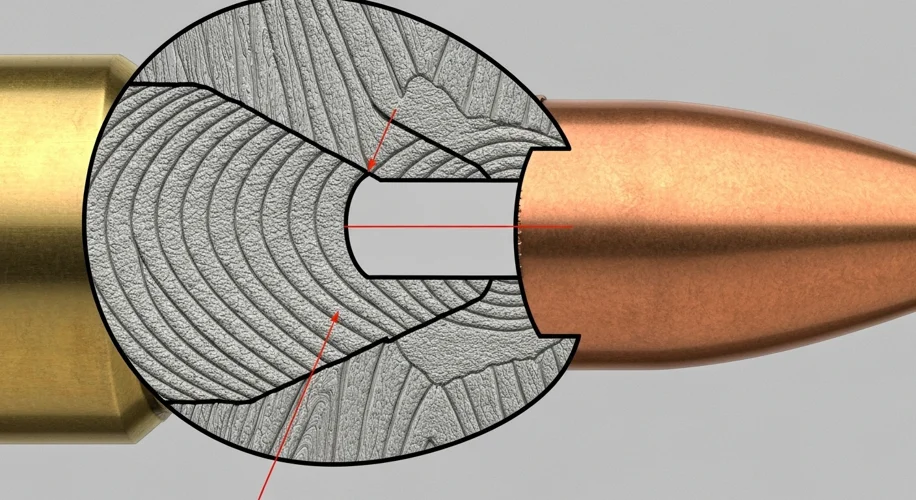

Early pioneers in this field recognized that the rifling within a gun barrel, as it propels a bullet, engraves microscopic striations onto its surface. These striations are not uniform; they are as unique as a human fingerprint. Similarly, firing pins, ejectors, and extractors all leave their own distinct marks on cartridges. The challenge was to develop the methodologies and the tools to analyze these microscopic details.

One of the most pivotal moments in the history of firearms examination came with the infamous Sacco and Vanzetti case in the 1920s. Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, Italian immigrants and anarchists, were convicted of murder during a payroll robbery. Central to their conviction was ballistics evidence presented by a firearms examiner, who claimed to have matched bullets found at the scene to Sacco’s .32 caliber Colt pistol. However, the testimony and the methodologies used were later heavily scrutinized, raising questions about the reliability of early ballistics analysis and sparking debate that continues to resonate in legal circles today.

As the 20th century progressed, the field of firearms examination evolved. Agencies like the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) and numerous state and local police departments established dedicated forensic laboratories. These labs became centers of innovation, housing increasingly sophisticated equipment like comparison microscopes, which allow examiners to view two bullets or cartridge cases side-by-side, facilitating direct comparison of their microscopic markings.

The development of standardized databases for firearms and ammunition, like the National Integrated Ballistics Information Network (NIBIN), marked another significant leap forward. NIBIN allows law enforcement agencies across the country to enter and search ballistic data from crime scenes and recovered firearms, creating a powerful tool for identifying potential links between seemingly unrelated crimes. This interconnectedness has been crucial in dismantling criminal organizations and preventing future violence.

The role of the firearms examiner extends far beyond simply matching bullets. They are responsible for a myriad of tasks, including:

- Firearm Functionality Testing: Ensuring firearms are in working order and understanding their firing characteristics.

- Ammunition Analysis: Examining bullets, cartridge cases, and shot for class and individual characteristics.

- Toolmark Identification: Identifying marks left by tools other than firearms, such as those left by crowbars or knives.

- Reconstruction of Events: Using ballistic evidence to help reconstruct the sequence of events at a crime scene.

- Expert Testimony: Presenting complex scientific findings clearly and concisely in court, where their testimony can be critical in determining guilt or innocence.

Consider the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in 1929. While the immediate perpetrators were never definitively brought to justice, the firearms used in that infamous event left behind a trove of evidence. In later years, advancements in ballistics examination and the creation of databases would allow investigators to link some of those weapons to other crimes, offering a chilling glimpse into the scope of organized crime’s violence.

The challenges faced by firearms examiners are significant. They work with evidence that is often degraded, incomplete, or contaminated. They must remain impartial, adhering to rigorous scientific protocols, even when the stakes are incredibly high. The pressure to provide definitive answers in cases involving murder, assault, and other violent crimes is immense. Furthermore, the legal landscape is constantly evolving, requiring examiners to stay abreast of new scientific techniques and legal challenges to forensic evidence.

In recent years, questions have arisen regarding the subjectivity inherent in some aspects of firearms comparison. While the underlying principle of unique striations is scientifically sound, the interpretation of these marks can, in some instances, involve a degree of expert judgment. This has led to calls for greater standardization, automation, and independent validation of methodologies. Nevertheless, the fundamental value of firearms examination in the pursuit of truth and justice remains undeniable.

From the early, rudimentary comparisons of bullets to the sophisticated digital analysis of today, the firearms examiner has evolved into an indispensable component of the American justice system. They are the silent arbiters, the forensic detectives who, with unwavering dedication and scientific rigor, help ensure that the echoes of violence do not go unheard and that justice, however delayed, ultimately prevails.