The year is 1803. The United States, a young nation still finding its footing, has just doubled its size with the Louisiana Purchase. But this vast new territory, stretching from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, is largely a mystery. Who lives there? What are its resources? Can a water route to the Pacific Ocean be found?

President Thomas Jefferson, a man consumed by curiosity and a vision for westward expansion, tasked Captain Meriwether Lewis with an audacious mission: to lead an expedition across this unknown wilderness. Lewis, a keen observer and skilled outdoorsman, chose his trusted friend, Second Lieutenant William Clark, to co-command. Together, they would lead the Corps of Discovery into the heart of a continent, a journey that would etch their names into the annals of American history.

The Seeds of an Expedition

Jefferson’s motivations were manifold. He sought to understand the geography, flora, and fauna of the Louisiana Purchase, to establish relations with Native American tribes, and, crucially, to find a passage to the Pacific, a dream that had eluded explorers for centuries. This wasn’t merely a scientific endeavor; it was a bold assertion of American sovereignty over lands few Americans had ever seen.

Lewis, meticulously preparing for the journey, gathered supplies, studied cartography, and honed his scientific skills. He was entrusted with detailed instructions from Jefferson, encompassing everything from diplomatic protocols for encountering indigenous peoples to the precise methods for collecting and preserving specimens.

Clark, known for his practicality and leadership, assembled a diverse group of men. These included soldiers, woodsmen, interpreters, and even Clark’s enslaved African American, York. Their journey would be long, arduous, and fraught with peril.

Embarking into the Unknown

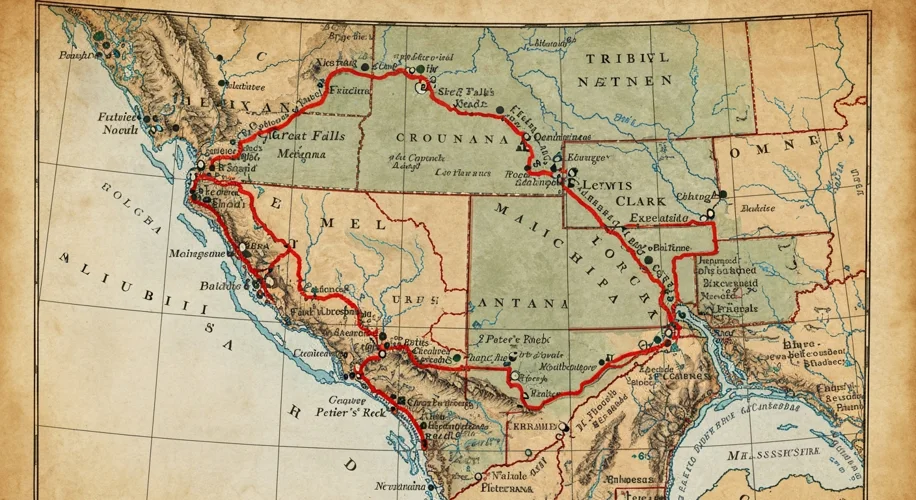

On May 14, 1804, the Corps of Discovery set off from Camp Dubois, near St. Louis, Missouri. Their vessels, a keelboat and two pirogues, navigated the mighty Missouri River, a watery highway leading them deeper into uncharted territory. The initial days were a testament to the sheer scale of the undertaking. The Missouri, often sluggish and winding, presented a formidable challenge, its currents and snags testing the endurance of the men.

As they pushed westward, the landscape transformed. The familiar forests of the East gave way to the vast, undulating prairies of the Great Plains. The air, once thick with the scent of pine, now carried the dry, earthy aroma of endless grasslands. Bison herds, numbering in the thousands, thundered across the plains, a breathtaking spectacle of untamed nature.

The expedition’s encounters with Native American tribes were a critical component of their mission. Their first significant encounter was with the Teton Sioux in present-day South Dakota. While initially cordial, tensions flared, leading to a tense standoff. Lewis and Clark, however, managed to de-escalate the situation, demonstrating a diplomatic finesse that would be crucial throughout their journey.

The Crossroads: Reaching the Pacific

The true test of the expedition’s resolve came as they approached the formidable Rocky Mountains. The sheer, snow-capped peaks loomed in the distance, a seemingly insurmountable barrier. It was here that they encountered Sacagawea, a young Shoshone woman who, along with her husband Toussaint Charbonneau, would become an indispensable member of the Corps. Sacagawea’s knowledge of the land, her ability to communicate with various tribes, and her sheer resilience proved invaluable.

Crossing the Rockies was a brutal ordeal. Food was scarce, the terrain treacherous, and the weather unforgiving. They faced hunger, exhaustion, and the constant threat of the elements. Yet, driven by the promise of the Pacific, they pressed on.

In November 1805, after 18 months of arduous travel, the Corps of Discovery finally reached their goal: the vast, shimmering expanse of the Pacific Ocean. The sight of the endless water, the roar of the waves, and the salty tang of the air must have been an overwhelming reward for their perseverance.

The Return and Legacy

The return journey, beginning in March 1806, was less about discovery and more about retracing their steps, albeit with a newfound understanding of the continent. They split into two groups for a portion of the journey to explore more territory, eventually reuniting before reaching St. Louis on September 23, 1806, bringing with them invaluable maps, detailed journals, and a wealth of scientific knowledge.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition was more than just a geographical survey; it was a profound cultural exchange, a scientific undertaking, and a testament to the indomitable spirit of exploration. Their journals provided the first detailed accounts of the American West for many Americans, revealing its diverse landscapes, its rich biodiversity, and the complex societies of its indigenous peoples. While the expedition contributed to the westward expansion of the United States, its enduring legacy lies in the meticulous record-keeping that illuminated a continent and inspired generations of explorers and scientists.

Their journey, a daring leap into the unknown, forever changed the American understanding of its own vastness and potential.