The Soviet Union. A name that, for decades, conjured images of stoic resolve, ideological fervor, and, perhaps most dramatically, a rocket-powered ascent into the cosmos. For a significant period, the Soviet space program was not just a symbol of national pride; it was the undisputed leader of humanity’s venture beyond Earth. From Yuri Gagarin’s historic first flight in 1961 to the groundbreaking Luna missions that touched the Moon, the Soviets were pioneers, pushing the boundaries of what was thought possible.

But as the 1970s bled into the 1980s, a subtle, then not-so-subtle, unraveling began. The once-unstoppable juggernaut of Soviet space ambition started to falter, its dominance slipping away not with a bang, but with a series of frustrating delays, ambitious projects left unfulfilled, and a growing chasm between their aspirations and their capabilities.

The roots of this decline are complex, interwoven with the broader socio-economic and political fabric of the Soviet Union itself. The Cold War space race, while a powerful motivator, was also an immense drain on resources. The Soviet economy, already struggling under the weight of military spending and centralized planning, found it increasingly difficult to sustain the massive investment required for cutting-edge space technology. While the West, particularly the United States with its Apollo program, demonstrated a remarkable ability to mobilize resources and innovate, the Soviet system, though capable of astonishing feats, began to show cracks.

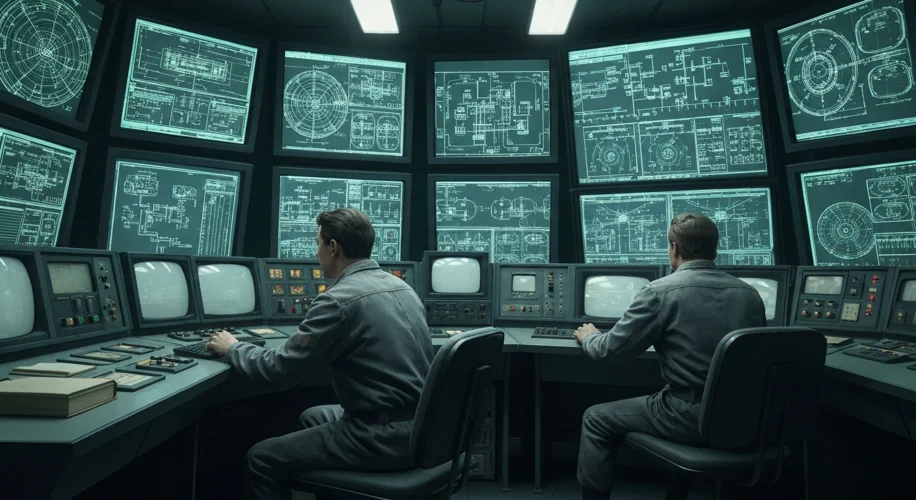

One of the most significant factors was the Soviet Union’s approach to secrecy and internal competition. While secrecy was inherent to the Soviet system, in the space program, it bred inefficiency. Different design bureaus, often working in parallel and without full knowledge of each other’s progress, competed for limited funding and resources. This stifled collaboration and duplicated efforts. The N1 rocket, the Soviet answer to America’s Saturn V, is a stark example. Multiple powerful design bureaus were tasked with developing its engines, leading to a chaotic and ultimately unsuccessful program that suffered catastrophic failures, including four failed launches between 1969 and 1972. The dream of beating America to the Moon died with the N1.

The human element was also crucial. Sergei Korolev, the brilliant Chief Designer whose vision and leadership propelled the early Soviet successes, died tragically in 1966. His successor, Vasily Mishin, lacked Korolev’s charisma and political acumen, struggling to maintain the program’s momentum and navigate the treacherous waters of Soviet bureaucracy. The loss of Korolev was a blow from which the Soviet crewed spaceflight program never fully recovered its early dynamism.

As the 1970s progressed, the focus shifted. While the US moved on from lunar exploration, the Soviets concentrated on developing long-duration space stations. Salyut and later Mir became testaments to their endurance in space, demonstrating a unique capability for sustained human presence. However, these achievements, while impressive, did not capture the global imagination in the same way the race to the Moon had. The ambition to land cosmonauts on the Moon, a key objective, was effectively abandoned.

The late 1970s and 1980s saw a further decline in capabilities. The Buran program, a Soviet space shuttle, was a technological marvel, culminating in a single, uncrewed orbital flight in 1988. However, it was incredibly expensive and ultimately served little purpose, a grand gesture that came too late. The program was a drain on already strained resources, and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 would render it entirely obsolete.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Soviet space program was a shadow of its former glory. Funding cuts were severe, brain drain began to set in as talented individuals sought opportunities elsewhere, and the aging infrastructure struggled to keep pace with technological advancements elsewhere. The once-proud symbol of Soviet technological prowess was now hobbled by economic stagnation and systemic inefficiencies.

The legacy of the Soviet space program is a complex tapestry of triumphs and tragedies. It undeniably played a pivotal role in human space exploration, laying the groundwork for many of the technologies and practices we rely on today. The Soyuz spacecraft, a direct descendant of their early designs, remains a workhorse of international spaceflight, a testament to the enduring quality of Soviet engineering.

However, the story also serves as a cautionary tale. It highlights how political and economic systems can profoundly impact scientific and technological progress. The intense competition, secrecy, and resource misallocation that characterized the Soviet system ultimately hindered its ability to maintain its early lead. The dream of Soviet cosmonauts planting their flag on the Moon, a dream that once seemed so tantalizingly close, became another casualty of a collapsing empire.

Today, the successor to the Soviet space program, Roscosmos, continues to be a key player in international space endeavors. Yet, the echoes of its once-unrivaled dominance serve as a powerful reminder of the dynamic and often precarious nature of scientific ambition on the grandest stages of human history. The stars, once a Soviet domain, are now a shared frontier, a legacy forged in both the brilliant ascents and the gradual, poignant declines of a bygone era.