In the hushed halls of religious institutions, where sanctity and spiritual guidance were meant to be paramount, a dark undercurrent flowed for centuries, largely unseen and unheard by the outside world. Before the seismic shifts of the early 2000s brought these abuses into stark public view, a pervasive pattern of clerical abuse and so-called ‘private companionship’ afflicted countless victims within the folds of religious orders. This was not a recent phenomenon; it was a deeply entrenched issue woven into the fabric of societal norms and institutional practices, a shadow that loomed large over the pre-2000 era.

To understand this hidden history, we must first step back into a world where religious authority often superseded secular law, and where the perceived purity of the clergy was fiercely guarded. In many Western societies, particularly those with strong Catholic traditions, priests and other religious figures held immense social and moral standing. Their pronouncements carried weight, their counsel was sought, and their institutions were often seen as bastions of virtue. This elevated status, coupled with a culture of obedience and deference, created an environment ripe for exploitation.

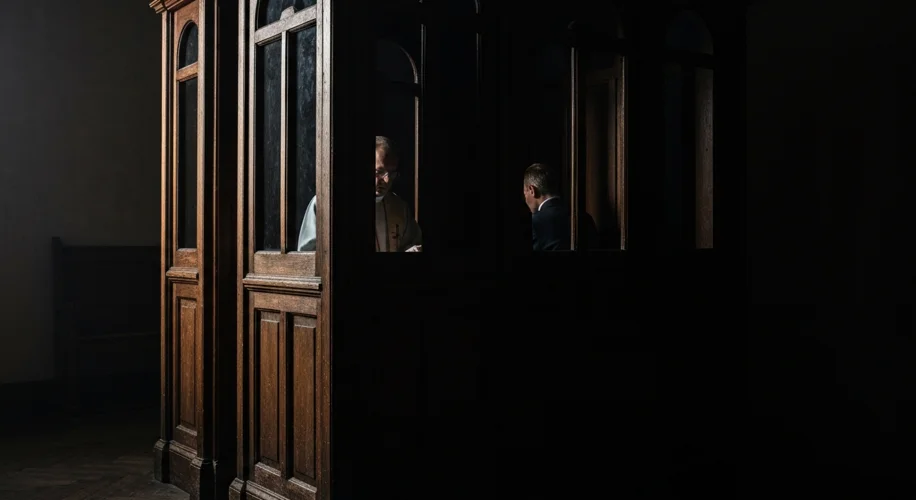

The concept of ‘private companionship,’ often a euphemism for homosexual relationships, was particularly fraught within religious orders that enforced celibacy. While the vow of celibacy was intended to dedicate individuals entirely to God, the inherent human need for connection and intimacy could, in some cases, lead to clandestine relationships. However, the pressure to maintain appearances and the fear of scandal often resulted in secrecy, which in turn could breed unhealthy dynamics and a climate where abuse could fester, hidden behind a veil of religious devotion.

The historical context is crucial. For much of the pre-2000 period, openly discussing or even acknowledging the existence of homosexuality within the clergy was largely taboo. This societal homophobia, coupled with the institutions’ own internal codes of silence, meant that any instances of abuse, whether sexual or otherwise, were often met with denial, minimization, or outright cover-ups. The focus was invariably on protecting the institution’s reputation rather than on seeking justice for the victims.

Key actors in this drama were not only the abusers and the victims, but also the institutional leaders – bishops, cardinals, abbots, and their appointed officials. Their decisions, driven by a complex mix of fear of scandal, adherence to rigid doctrines, and perhaps a misguided sense of protecting the Church’s flock, often prioritized damage control over accountability. Victims, frequently young men or boys within seminaries, religious schools, or parishes, were often isolated, their accusations dismissed, and their faith itself used as a tool to silence them. The concept of ‘obedience’ and the fear of eternal damnation were potent weapons in the abuser’s arsenal.

One cannot speak of this era without acknowledging the systemic nature of the problem. While individual cases of abuse existed, it was the institutional response – or lack thereof – that allowed the problem to persist. Records, where they exist, often show patterns of ‘transfer’ rather than ‘removal,’ moving problematic clerics from one parish or diocese to another, effectively passing the burden and the danger onto new communities. This was not merely a series of isolated incidents; it was a failure of oversight, a betrayal of trust on a grand scale.

The consequences for victims were, and remain, devastating. They carried the scars of abuse, often in silence for decades, grappling with trauma, shame, and a profound sense of betrayal by those they were taught to revere. The impact extended beyond the individual, eroding trust in religious institutions and communities.

The pre-2000 era represents a period where the systemic issues surrounding clerical abuse and the ‘private companionship’ within religious orders were deeply embedded, shielded by societal taboos and institutional cover-ups. While the early 2000s marked a turning point with increased media attention and legal action, the history leading up to it is one of pervasive silence, profound harm, and a long, arduous struggle for accountability that continues to echo today.

The societal norms of the time, which often placed religious figures on a pedestal and viewed discussions of sexuality, especially homosexuality, as deeply shameful, provided fertile ground for abuse to flourish undetected. The vow of celibacy, intended to foster spiritual devotion, tragically became a cloak for predatory behavior in some instances, particularly when coupled with the institutional imperative to maintain an image of spotless rectitude.

Consider the case of Father John Geoghan, whose decades of abuse in the Boston Archdiocese, only fully exposed in the early 2000s, were but one piece of a much larger, systemic puzzle. While Geoghan’s actions were reprehensible, the pattern of his transfers within the archdiocese, a practice noted in numerous investigations, highlighted how institutional mechanisms, rather than individual failings alone, perpetuated the harm. This pattern was not unique to Boston or to the Catholic Church; similar dynamics played out in various religious orders and denominations across the globe.

The struggle for victims to be heard was often a solitary one. Many recounted being disbelieved or actively discouraged from speaking out by church authorities, who feared damaging the institution’s reputation more than protecting its vulnerable members. The spiritual authority wielded by priests could be immense, and the threat of excommunication or spiritual condemnation was a powerful deterrent against any attempt to break the silence. This created a cycle of abuse and cover-up that spanned generations.

It is vital to remember that this history is not merely an academic exercise. It is the lived experience of countless individuals whose lives were irrevocably altered by the betrayal of trust within sacred spaces. Understanding this pre-2000 era is not about assigning blame to every cleric or every institution, but about recognizing the deep-seated systemic issues that allowed such harm to occur and persist for so long, and learning from this painful legacy to ensure that such shadows are never allowed to engulf the light of faith again.