In the grand tapestry of human history, where empires rise and fall and civilizations are built on a foundation of complex laws and shifting morals, one thread has often been overlooked: our relationship with the animal kingdom. For centuries, animals were viewed as mere property, their suffering a trivial matter in the face of human concerns. But a slow, persistent tide of empathy began to turn the wheels of justice, leading to the animal cruelty legislation we recognize today.

The story doesn’t begin with grand pronouncements of animal rights. Instead, it’s a narrative woven from small acts of kindness, public outcry, and the persistent efforts of individuals who saw beyond the utility of animals to their capacity for pain and fear.

From Property to Persons: The Early Stirrings

For much of human history, the concept of animal welfare was virtually non-existent. Animals were tools, food sources, or beasts of burden. Laws that did exist primarily focused on preventing damage to property. If a neighbor’s ox wandered into your field and was injured, the concern was the loss of your neighbor’s property, not the ox’s suffering. This utilitarian view, deeply embedded in legal and social structures, made any consideration of animal rights seem outlandish.

However, whispers of dissent began in the shadows of religious and philosophical thought. Some ancient cultures, like certain Hindu traditions, held animals in high regard, advocating for non-violence. Philosophers like Pythagoras in ancient Greece reportedly advocated for vegetarianism, believing in the transmigration of souls and thus, a kinship with animals.

But it was in 18th-century England that the seeds of modern animal welfare legislation were truly sown. The Enlightenment, with its emphasis on reason and individual rights, inadvertently opened doors for considering the rights of other sentient beings. Thinkers like Jeremy Bentham, a prominent utilitarian philosopher, famously stated in 1789: “The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?” This simple yet profound question shifted the focus from intellectual capacity to the undeniable reality of pain.

The First Sparks: Early Legislation and Public Outcry

One of the earliest legislative victories came not for farm animals or domestic pets, but for those subjected to the horrors of vivisection – the dissection of living animals for experimental purposes. In 1822, Richard Martin, an Irish politician, championed the “Ill-Treatment of Cattle Act,” often called “Martin’s Act.” This landmark legislation made it a criminal offense to cruelly ill-treat horses and cattle. While seemingly narrow in scope, it was revolutionary for its time, establishing the principle that humans had a legal duty to prevent animal suffering.

Martin’s efforts, however, were met with considerable resistance. He was often mocked and derided for his “animalitarian” views. Yet, his persistence paved the way for further reforms.

The mid-19th century saw the formation of the first dedicated animal protection societies. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) was founded in 1824, initially as the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Its early work was arduous, focusing on educating the public and prosecuting offenders under Martin’s Act. Public spectacles like bull-baiting and dog-fighting, though brutal, began to face increasing condemnation. The vivid descriptions of suffering in newspapers and pamphlets, coupled with the tireless advocacy of groups like the RSPCA, gradually chipped away at public indifference.

Expanding the Circle of Protection: Landmark Legislation

Building on the momentum, further legislation expanded protections. The Cruelty to Animals Act of 1835 in Britain broadened the scope of animal protection beyond just cattle and horses to include other domestic animals and clarified punishments for ill-treatment. This was a crucial step in recognizing that suffering was not limited to specific species.

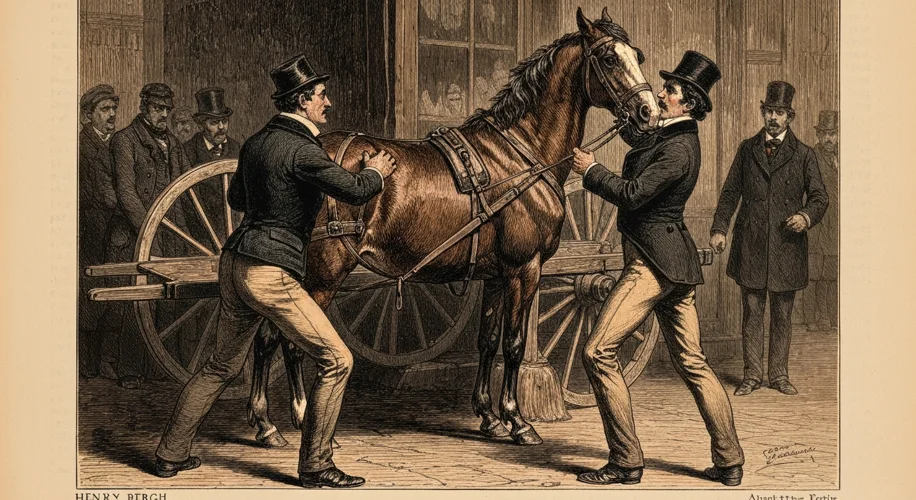

In the United States, the movement gained traction in the latter half of the 19th century. New York passed an anti-cruelty law in 1866, largely due to the efforts of Henry Bergh, who founded the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA). Bergh, inspired by his experiences in England and France, became a passionate advocate, often intervening personally to rescue abused animals and bringing offenders to court. His work faced similar ridicule to Martin’s, but his unwavering resolve was instrumental in establishing animal protection laws in the U.S.

The early 20th century saw continued progress. The Humane Slaughter Act was passed in the United States in 1958, requiring that livestock be rendered insensible to pain before slaughter. While criticized by some as insufficient, it represented a significant ethical shift, acknowledging that animals raised for food deserved a humane end.

The Modern Era: Evolving Ethics and Broader Rights

As society progressed, so did the understanding of animal sentience and welfare. The latter half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century witnessed a surge in animal rights activism and a more sophisticated legal framework. The focus expanded beyond preventing overt cruelty to addressing issues like:

- Factory Farming: Concerns grew about the conditions in large-scale agricultural operations, leading to debates and legislation regarding cage sizes, confinement, and living conditions for animals raised for food.

- Animal Testing: The ethics of using animals in scientific research, cosmetics, and pharmaceutical testing became a major point of contention. Legislation like the Animal Welfare Act in the U.S. (first passed in 1966 and amended multiple times) established standards for the humane care and treatment of animals used in research.

- Companion Animals: Laws evolved to recognize the bond between humans and their pets, leading to regulations on pet breeding, sales, and stronger penalties for abandonment and abuse.

- Wildlife Protection: Legislation shifted from purely conservationist goals to protecting individual animals from harm, such as laws against poaching and the illegal trade of endangered species.

Key figures and organizations continued to push the boundaries. Philosophers like Peter Singer, with his influential book “Animal Liberation” (1975), brought utilitarian arguments about animal suffering into mainstream discourse, advocating for what he termed “speciesism” to be challenged. Movements like PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) emerged, using direct action and public awareness campaigns to highlight animal welfare issues.

Today, the landscape of animal cruelty legislation is diverse and continually evolving. While many countries have robust laws, enforcement can be inconsistent, and the definition of “cruelty” can still be debated. However, the trajectory is undeniable: from viewing animals as mere objects, we have moved towards recognizing their capacity for suffering and, increasingly, their intrinsic value.

The history of animal cruelty legislation is a testament to the power of empathy and persistent advocacy. It’s a story that reminds us that the measure of a society can often be found in how it treats its most vulnerable, including those who cannot speak for themselves. The echoes of those early struggles for humane treatment continue to resonate, urging us to consider our responsibilities to the creatures with whom we share this planet.